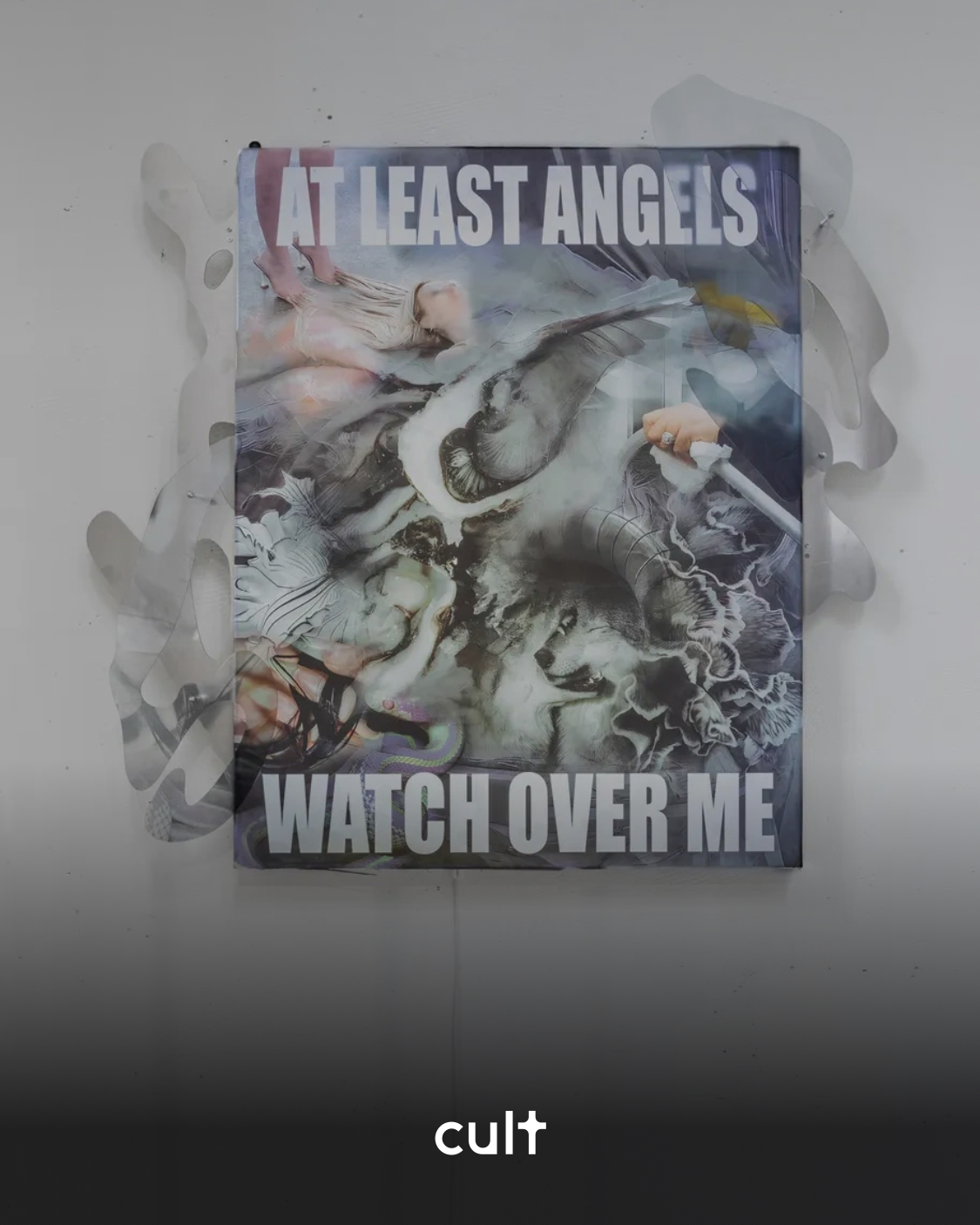

In AT LEAST ANGELS WATCH OVER ME, Natasha Perova stages a ghostly communion between tenderness and circuitry. Installed in the crumbling tiled skeleton of fābula HQ — a former industrial space that feels more morgue than gallery — her works pulse with a strange, machinic empathy.

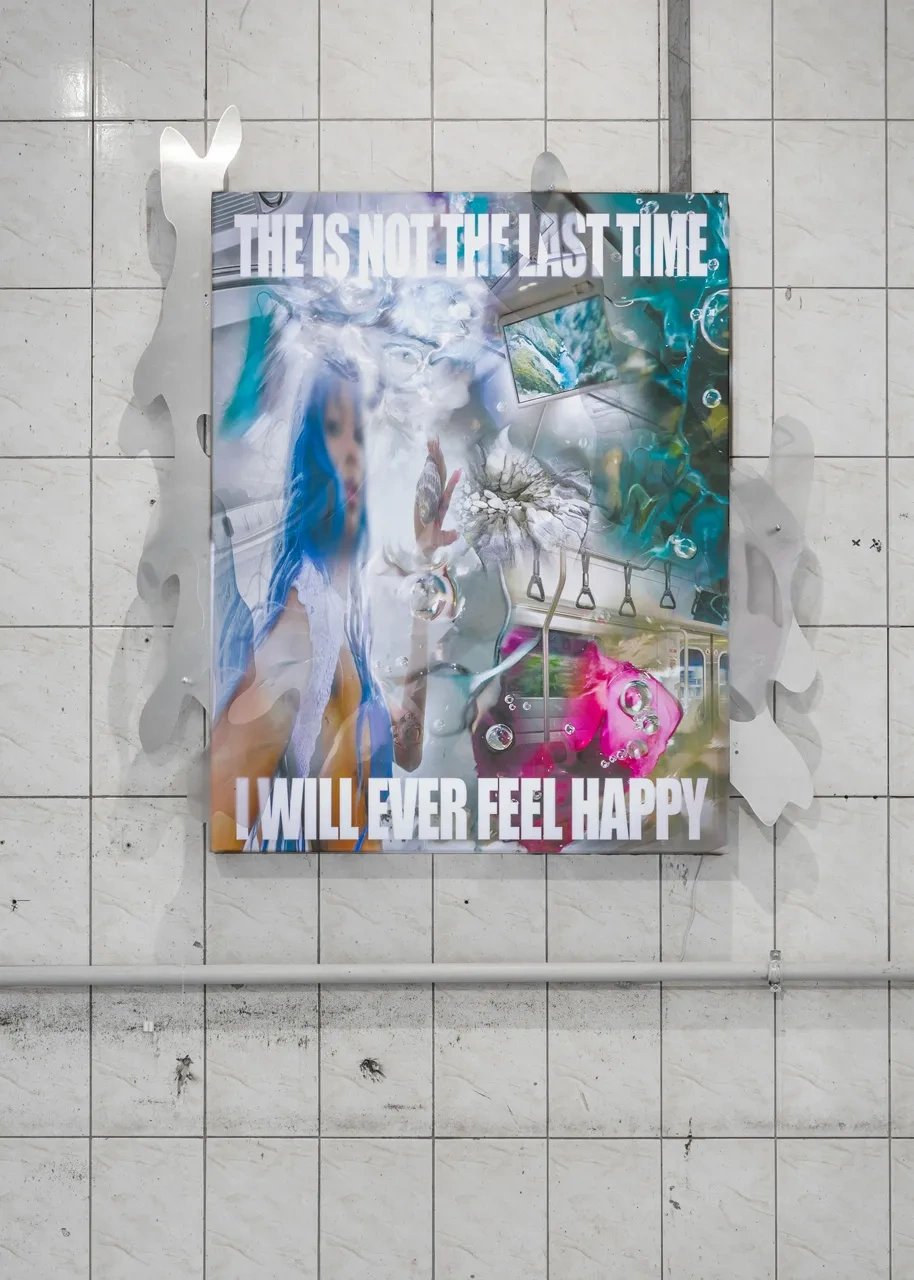

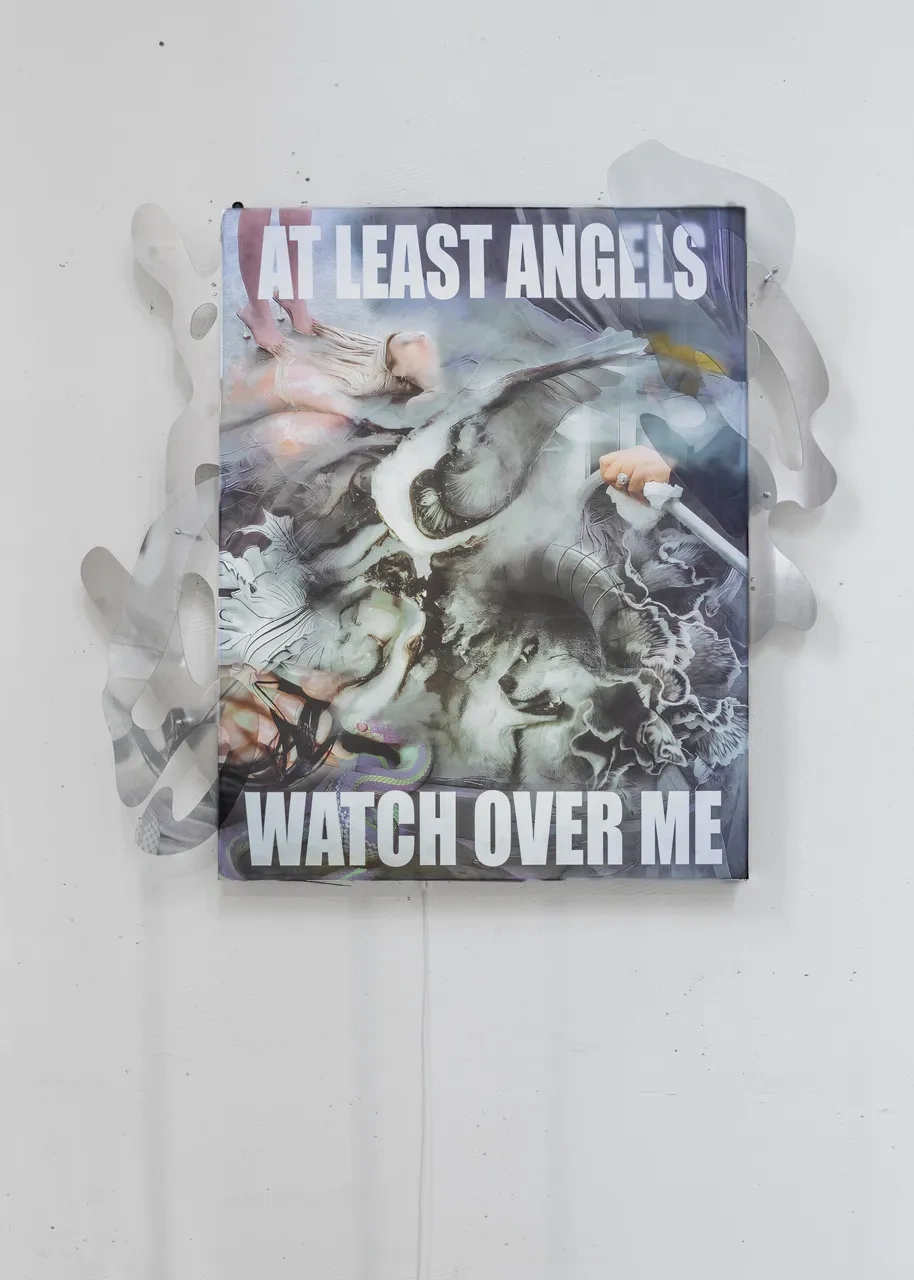

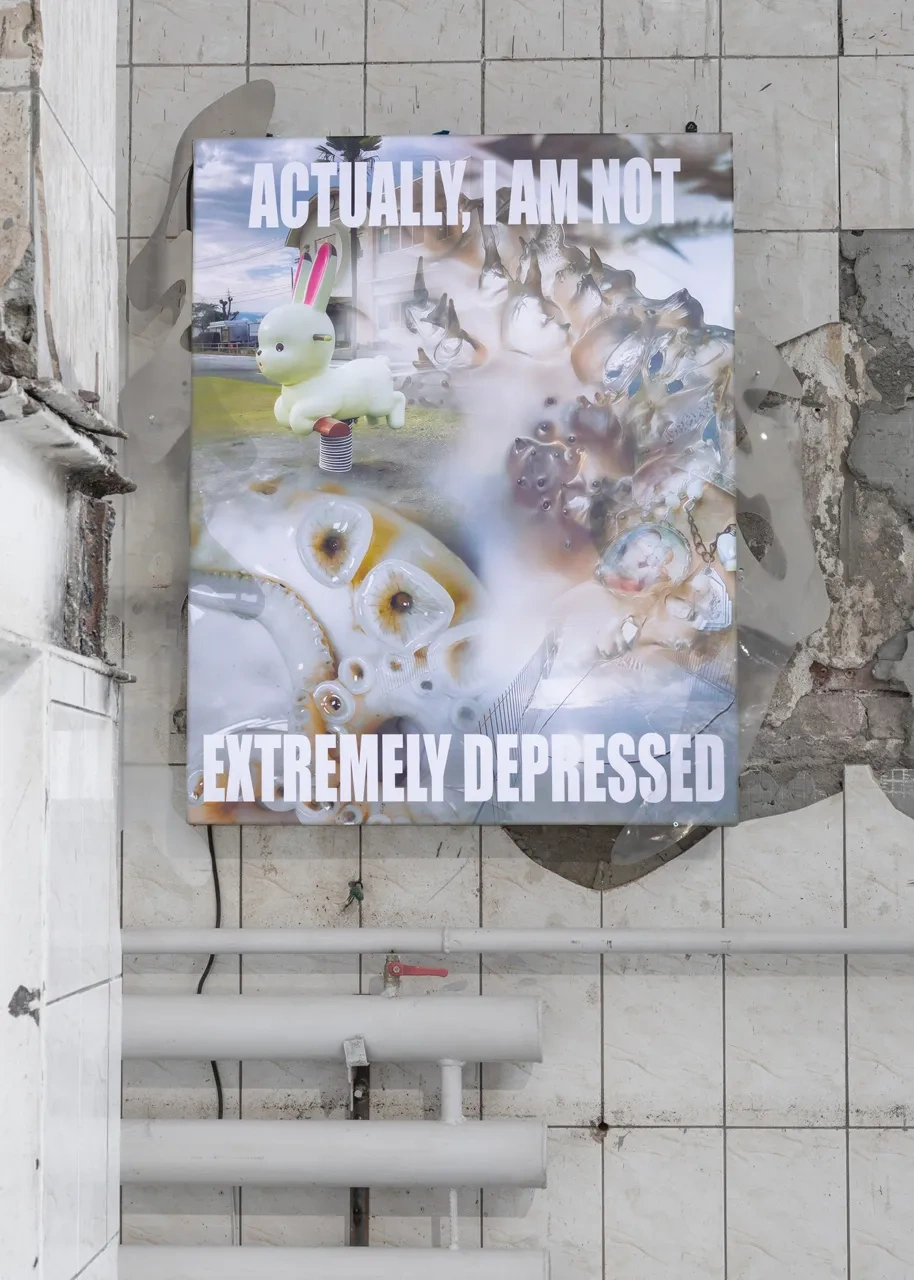

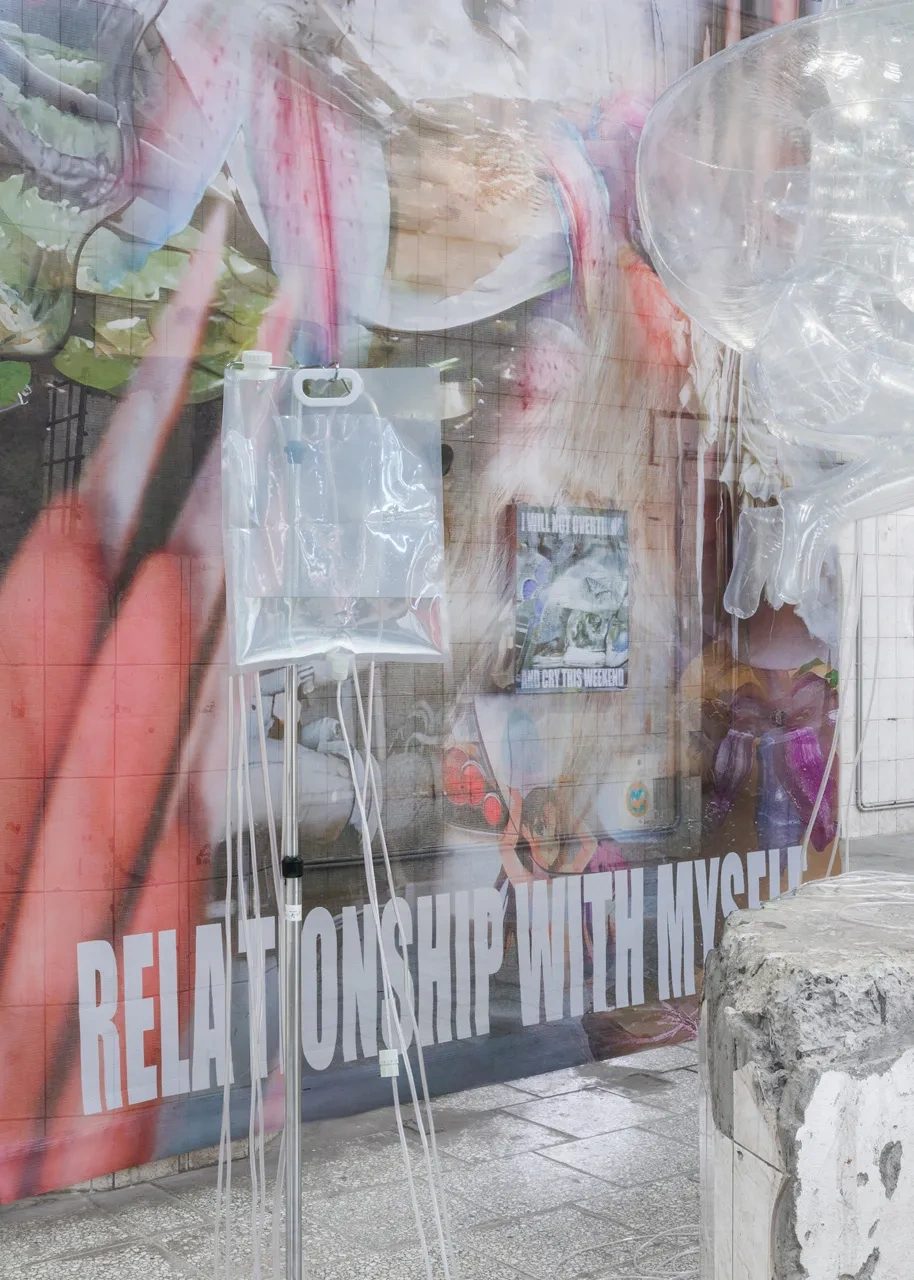

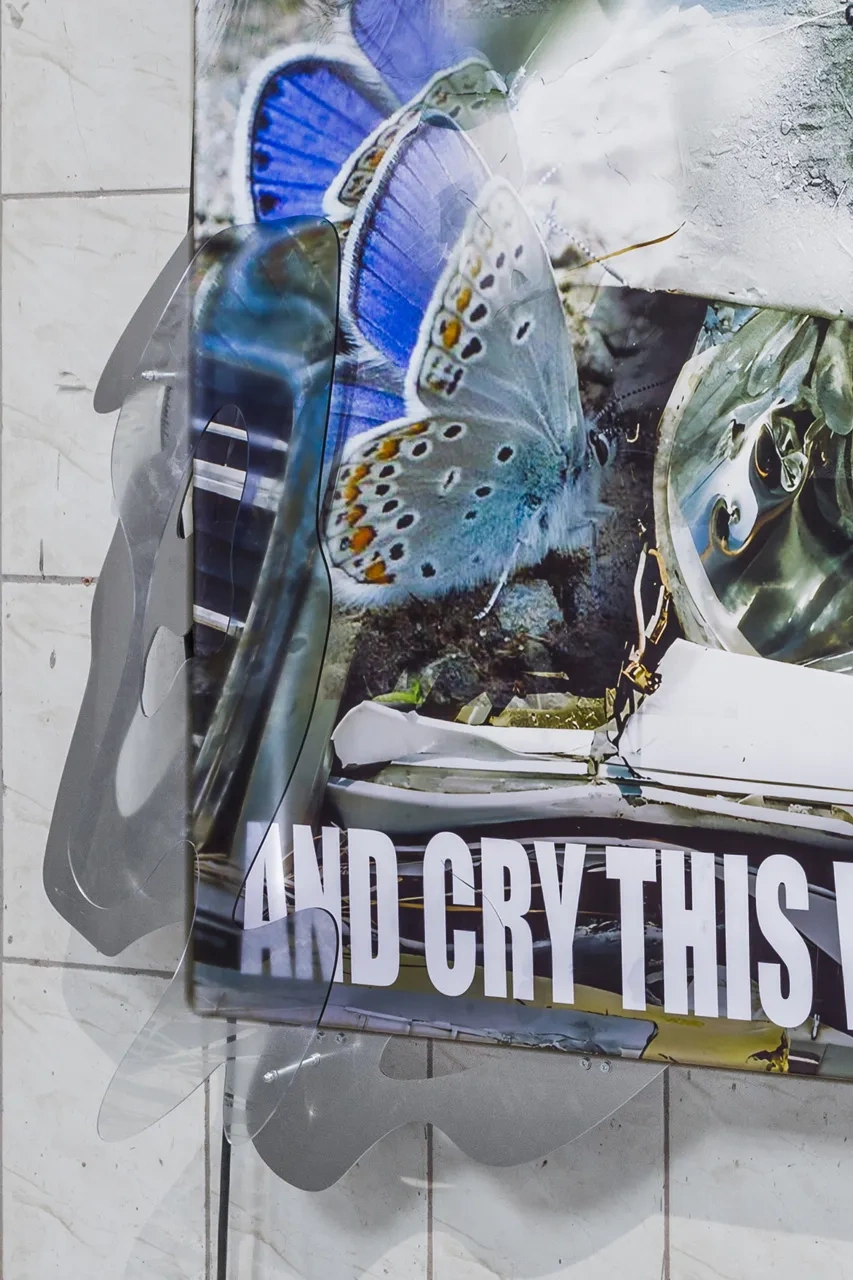

Transparent biomorphic forms dangle from IV drips, metallic organs glisten like failed prototypes, and across the walls hover digital prints with confessional slogans: “ACTUALLY, I AM NOT EXTREMELY DEPRESSED,” “I HAVE AN INCREDIBLE RELATIONSHIP WITH MYSELF.” The phrases feel lifted from the half-ironic optimism of the internet’s wounded self-help vernacular. It’s as if the artist has scraped the emotional residue of the post-digital self and pinned it against the tiles for autopsy.

Perova’s project channels Donna Haraway’s seminal A Cyborg Manifesto (1988), a text that imagined a politicized cyber-femme utopia liberated from the mythology of purity and binary gender. For Haraway, the cyborg was “a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction” — a hybrid rejecting salvation narratives, embracing the fluid, the broken, and the recombinant. Perova takes that lineage and mutates it through the language of contemporary vulnerability: irony, digital performance, and affective exhaustion. Her cyborg is not the defiant punk warrior of the 1980s feminist imaginary, but a fragile, semi-transparent organism suspended in existential uncertainty.

In Perova’s vision, the post-human isn’t cold or metallic; it’s fleshy, leaky, almost cute. The transparent plastic and soft tubing suggest both hospital apparatus and kawaii prosthetics. The “machine” has become an extension of affect rather than aggression — an interface for care, intimacy, and anxiety. It’s a far cry from the sleek techno-futurism of the early 2000s. Here, the cybernetic body is tenderly dysfunctional, closer to an emotional prosthesis than an instrument of empowerment.

What makes AT LEAST ANGELS WATCH OVER ME especially potent is its oscillation between sincerity and parody. The show’s visual language could easily belong to the aesthetics of vaporwave or AI-generated spirituality — the angelic motifs, pastel gradients, and internet-poetic affirmations. But beneath the surface irony lies something earnest: an attempt to locate softness within a system of digital exhaustion. Perova seems to ask whether self-parody is the only authentic mode of emotional expression left in a culture where irony and sincerity have collapsed into each other.

In one sense, her cyborg inherits Haraway’s hope for hybridity as a mode of liberation. Yet liberation here doesn’t look like transcendence; it looks like survival through self-design. The works’ mechanical drips, cables, and transparent shells echo the rhythms of contemporary digital existence — wired, dependent, and perpetually updating. These sculptures seem to breathe with the same anxious regularity as our online selves, calibrated through likes, views, and dopamine loops.

Perova’s angels — those fragile protectors of our algorithmic fatigue — are neither celestial nor human. They are symptomatic. Their watchfulness feels less divine than infrastructural, like the passive gaze of a cloud server monitoring your data. Still, the artist treats that surveillance with tenderness, as if acknowledging that even in our most synthetic moments, we remain capable of care.

The show’s strength lies in its refusal to moralize. Perova doesn’t propose an escape from the technological condition but instead inhabits it fully, aesthetically, even lovingly. The result is a vision of the post-human that is both broken and devotional — an affective architecture built from transparency, exhaustion, and a peculiar kind of grace. In a world where identity has become an interface, AT LEAST ANGELS WATCH OVER ME feels like a quiet act of faith in the possibility of feeling through the machine.