There is something unsettling about entering the Pantheon and being met, not by harmony, but by rupture. Beneath the vast dome — that ideal “dwelling of the divine” conceived in golden ratio and cosmic symmetry — Helga Vockenhuber installs Corona Gloriae: seven monumental bronze fragments adrift on a pool of black water, glinting beneath the oculus’ unrelenting light. It is not serenity they offer, but disturbance, an invitation into suffering.

Vockenhuber, one of Austria’s most internationally recognized artists, first presented the installation at the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore during the 2023 Venice Biennale. Now, reimagined for the Pantheon, the work takes on a site-specific dialogue that feels almost confrontational. “Among the buildings that come to us from antiquity adopting the measure of the golden ratio,” notes curator Don Umberto Bordoni, “the structure of the Pantheon best embodies the vision of an ideal ‘dwelling of the divine.’” Against this perfection, Corona Gloriae stages its counterpoint: a broken harmony, a jagged beauty that wounds as much as it redeems.

Photograph by Ägidius Vockenhuber

The work begins from a symbol as ancient as it is fraught: the crown of thorns. Traditionally, within Christian iconography, it is both humiliation and transfiguration — an emblem of sanctified violence, “a sign of love offered to the very end.” Vockenhuber fractures the relic into seven massive sculptures, scattered like debris from a cosmic wreck. Biblical numerology turns this fragmentation into possibility: seven is the number of creation, covenant, and redemption. The crown’s rupture signals not collapse but opening. Pain is no longer “hermetically clamped,” as the artist describes it, but “shared, so much so that it can be crossed.”

Placed directly beneath the Pantheon’s oculus — the “Eye of Heaven” — the bronzes appear caught between realms. Daylight pours through the circular void, illuminating twisted spikes and jagged shadows, reflected in the black pool below. It is as if the installation floats above an abyss, suspended between cosmos and chaos. The tension is deliberate: the Pantheon’s perfection absorbs Vockenhuber’s fragmentation, but does not resolve it. “There is a tragic tension that runs through the entire human history,” she says, “and that finds precisely on the face of the Ecce Homo crowned with thorns the emblem of a supreme awareness: My kingdom is not of this world.”

Photograph by Ägidius Vockenhuber

In this space, the theological becomes visceral. The sculptures recall driftwood after a storm — “castaways from every sea of the Earth,” as Bordoni describes them. Disfigured, mutilated forms. Shreds of roses long withered. Stems of thorns sharp enough to pierce both bearer and beholder. They suggest not only Christ’s suffering but the collective human wound — loneliness, exile, the splintering of meaning. And yet, suspended beneath the open sky, they are bathed in redeeming light.

“There is a tragic tension that runs through the entire human history, and that finds precisely on the face of the Ecce Homo crowned with thorns the emblem of a supreme awareness: My kingdom is not of this world.”

The Pantheon’s water, dark yet reflective, plays a crucial role: it absorbs the weight of the bronzes, mirroring their forms, holding memory. Here, reflection becomes a kind of baptismal mystagogy. Death, Vockenhuber suggests, is not erasure but passage. Pope Francis writes in the Bull of Indiction for the Jubilee of 2025: “Life is changed, not ended.” Corona Gloriae echoes this sentiment — suffering is not hidden away but transformed into a horizon of hope.

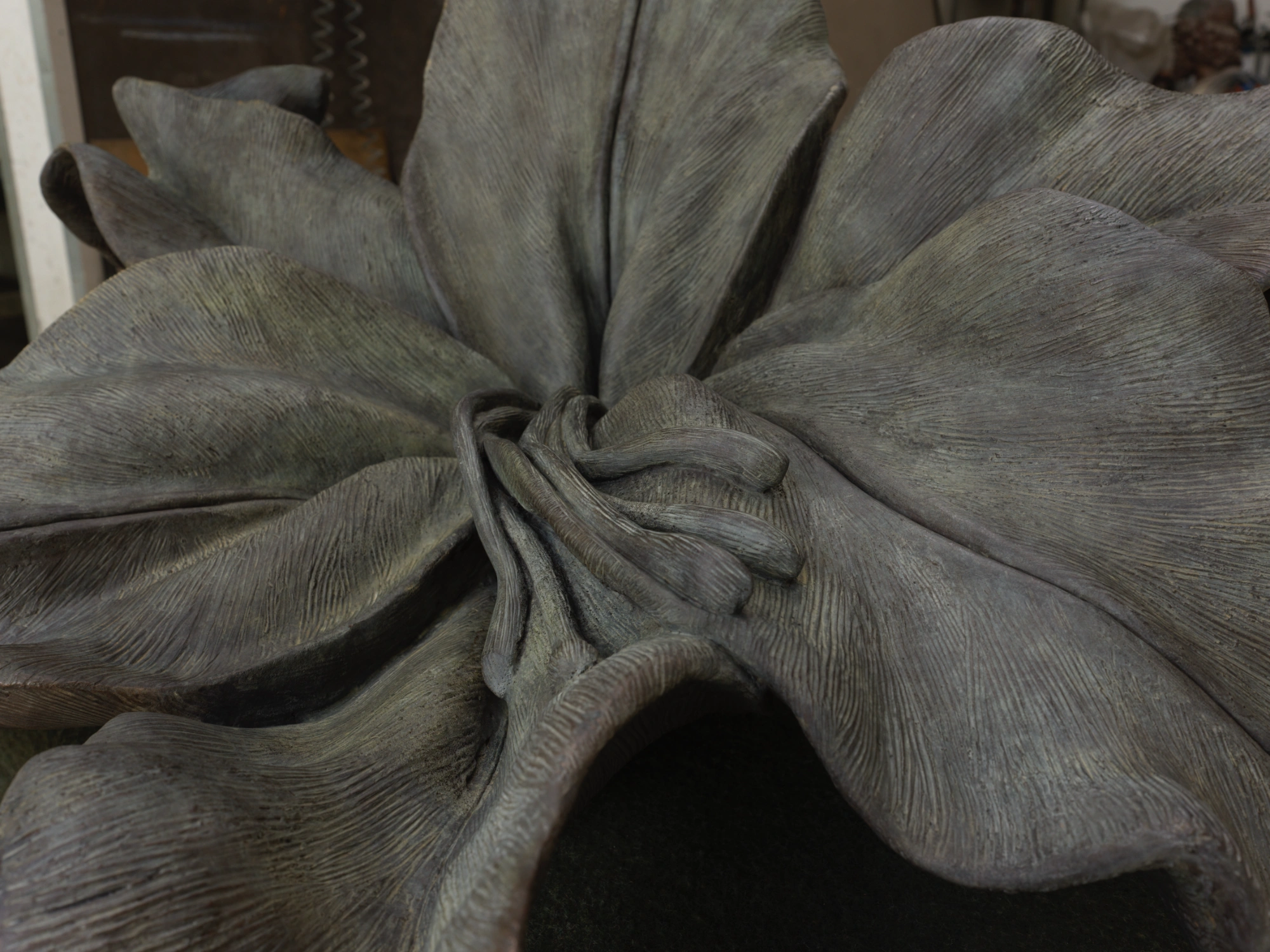

At the entrance, Vockenhuber positions an immense bronze Sea Lily, the pancratium of ancient Greece, a flower that blooms in arid sands, nourished by salt winds. It greets the viewer as a symbol of resilience: beauty that survives where survival seems impossible. This gesture frames the installation not as despair but as threshold.

Photograph by Ägidius Vockenhuber

Corona Gloriae is less about illustrating faith than enacting its paradox: the coexistence of rupture and redemption, chaos and cosmos, death and new life. Beneath the Pantheon’s dome — a structure designed to evoke divine perfection — Vockenhuber stages a confrontation. Her shattered crown does not complete the architecture’s symmetry; it wounds it, interrupts it, and in doing so, exposes a deeper truth: redemption is not the absence of suffering, but its transfiguration.

Between shadow and light, between ruin and resurrection, Corona Gloriae opens a space where sacredness is no longer a refuge from the world’s pain but, as the artist insists, “the womb of its redemption.”