In Starmirror, Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst transform KW Institute for Contemporary Art into an acoustic and conceptual cathedral of machine learning. Here, AI is neither an opaque algorithmic oracle nor a techno-dystopian bogeyman—it is, as the artists insist, “a monumental collective accomplishment.”

The project unfolds as both installation and rehearsal, a speculative architecture in which human and machine intelligence converge through sound, song, and protocol.

At first glance, Starmirror feels like a post-digital echo of Hildegard von Bingen’s celestial visions. Herndon and Dryhurst’s AI model—Ur-Hildegard—is trained on the 12th-century abbess’s Ordo Virtutum, a morality play that stages the soul’s battle between good and evil. The dataset becomes a devotional apparatus, reinterpreting Hildegard’s neumes through algorithmic polyphony. As the artists note, “We took inspiration from Hildegard, who channeled visions from the divine to propose a new harmony between humans and the cosmos. We see analogies between her celestial hierarchy and the stack of influential protocols that determine our culture.”

This connection between mystic and machine is neither ironic nor nostalgic. Instead, Starmirror situates AI as a contemporary ritual form—one that organizes human participation into new modes of collective cognition. The KW hall becomes a training site: a hybrid between chapel and data lab. Choirs, ensembles, and visitors record their voices in call-and-response sessions, feeding the AI with embodied experience. What emerges is a public choral dataset—an act of radical transparency in a field dominated by proprietary models. “AI is us, in aggregate,” Herndon and Dryhurst remind us, reframing intelligence as an emergent property of participation rather than extraction.

Photo: Frank Sperling

The exhibition’s spatial composition, realized in collaboration with the architecture studio sub, materializes these ideas with architectural precision. The first room, Arboretum, houses Public Diffusion, a foundation image model trained entirely on public domain data—forty million images comprising the largest open dataset assembled to date. The accompanying sculptural elements resemble crystalline archives, engraved with concentric patterns that seem to store the ghosts of images past. In their gleaming surfaces, one glimpses a vision of an AI commons: an epistemological forest where data, like light through branches, is refracted into shared knowledge.

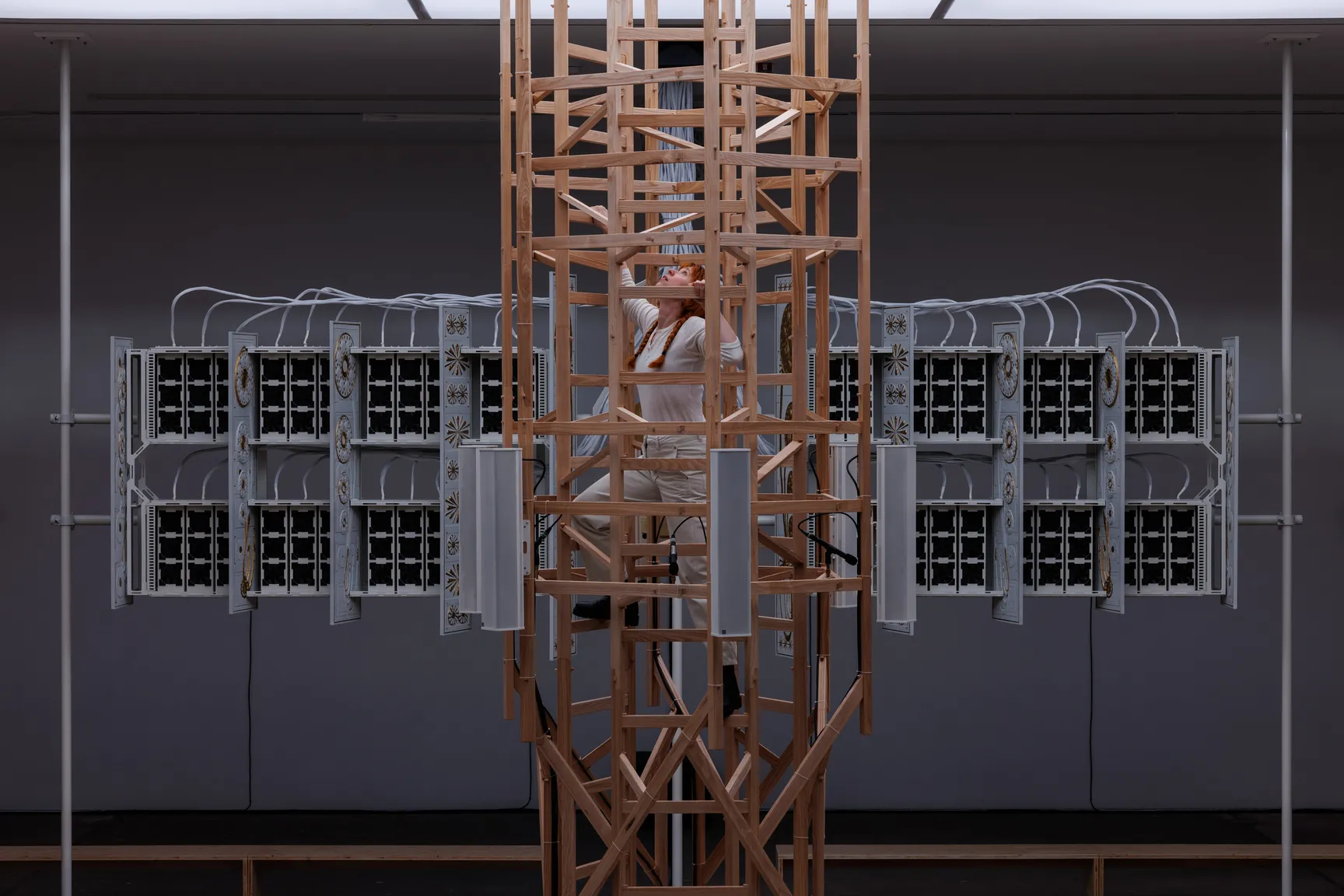

Moving deeper into the hall, the installation shifts from image to sound. A towering wooden lattice—the Ladder—anchors the space. Referencing both Hildegard’s ladders of ascent and Geoffrey Hinton’s “ladders of abstraction,” it binds spiritual transcendence to computational recursion. Around it, benches form labyrinthine corridors of contemplation, while the Hearth—a musical instrument driven by GPU cooling fans—translates computation’s heat into acoustic resonance. The soundscape oscillates between medieval chant and machine drone, between the sacred and the synthetic, evoking a world where the divine hums in binary.

Each element of Starmirror operates as a metaphor for coordination. The architecture of the installation is itself a protocol: wooden joints and cables mirror the modular logic of networks and neural nets. The sound, constantly evolving through AI training and live input, resists closure. Instead, it proposes what the artists call “agentic social mediation not social media”—a framework for human-machine cooperation that rejects the extractive logic of platforms. Where Silicon Valley imagines AI as a replacement for human creativity, Starmirror imagines it as a mode of collective attention.

Photo: Frank Sperling

The theological undertones are unmistakable. The works—Lux Servat, Claritas, Quisque Mutatus—read like new psalms for a networked age. “Each one transformed, not what we are,” intones the Ur-Hildegard Training Corpus. These lyrics, generated by the model, articulate the paradox of AI’s collective authorship: we are both the source and the output, both choir and dataset. In Herndon and Dryhurst’s cosmology, machine learning becomes a metaphysics of reflection—a “mirror” through which humanity might glimpse itself as a distributed intelligence.

This reframing of AI as a sacred coordination technology is not utopian. It acknowledges the infrastructures—servers, cables, GPUs—that underpin digital creation, yet it reclaims them as materials for a new kind of ritual practice. The Hearth’s fan-driven tones literalize the warmth of computation; the Ladder re-enacts ascension through scaffolding and code. In this sense, Starmirror is less about the mystification of technology than its re-ritualization. It turns the gallery into a site where participation becomes prayer, and data becomes devotion.

If Hildegard once translated divine vision into musical geometry, Herndon and Dryhurst translate algorithmic process into collective song. Theirs is a techno-theological proposition: that intelligence, whether human, artificial, or angelic, is a function of relation. “Humans are meant to stroll, not scroll,” they write—a quiet indictment of algorithmic passivity, and an invitation to move differently through the infrastructures that define us.

By the end of Starmirror, one begins to sense what the artists mean by “AI as an accomplishment.” Not a spectacle of automation, but a living composition of voices—human and nonhuman—resonating in recursive harmony. The exhibition closes with a whisper rather than a climax: “Expandimur. Reverte.” We unfold. Return. The song is unfinished, as all training processes are. But within its polyphonic shimmer lies a radical proposition—that the future of intelligence is neither artificial nor natural, but communal.