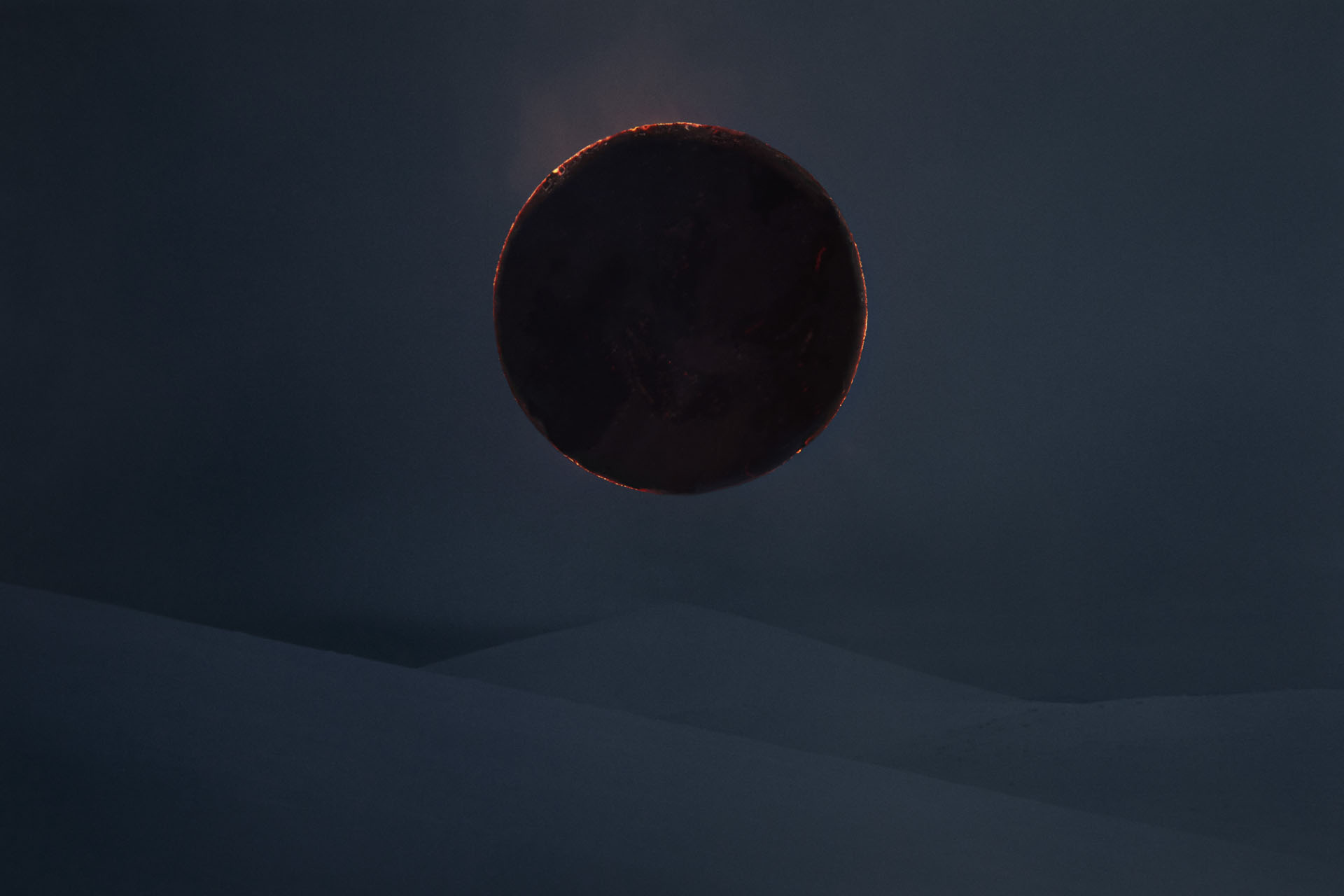

In Igor Elukov’s Book of Miracles, the Arctic is no longer a landscape—it’s an organism. A sentient, uncooperative entity that resists the artist’s control while collaborating with him in acts of quiet transcendence.

His world is one where theology dissolves into weather, where myth grows out of frozen soil, and where the sacred is found not in revelation, but in erosion.

Elukov, who grew up in Arkhangelsk on Russia’s Arctic fringe, builds his cosmology from the tundra’s visual contradictions: infinite and flat, yet unfathomably deep. “The barren monotonous plains distort any sense of perspective and scale,” he writes. The camera, typically a device of mastery and framing, becomes here an instrument of surrender. Every frame in Book of Miracles feels like the aftermath of a prayer—answered, perhaps, but not in human language.

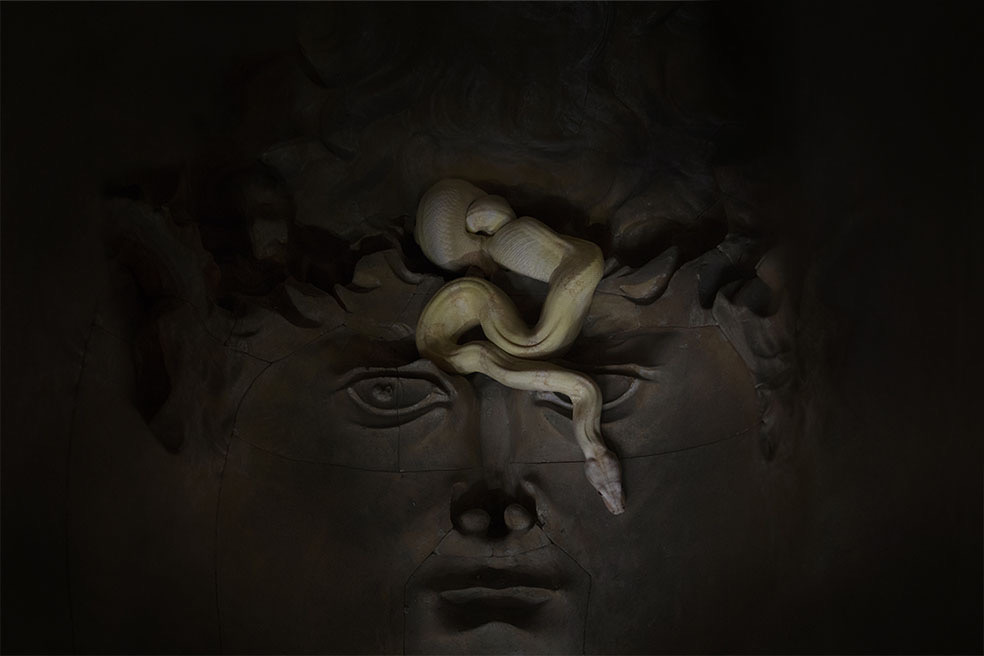

The project, an immense collaboration involving 40 people, livestock, and hand-built installations transported into the snow, operates on a scale more akin to cinema than photography. Indeed, Elukov’s reference points are cinematic: William Turner’s storms and Buster Keaton’s impossible stunts. “Technologically speaking, our approach is close to the pre-CGI era,” he says. “There aren’t any major post-production tricks… It’s a collaboration with life.” This insistence on physicality—the real cow stranded in an invented island, the camera foam catching fire in a smelter—suggests an ascetic devotion to process, a resistance to the sterile omnipotence of digital creation.

His image of the Jersey cow family, marooned on a sliver of wet sand as the tide closes in, distills this ethos perfectly. It’s absurd, tragic, serene: a pastoral hallucination at the edge of the world. “Then something miraculous happened,” Elukov recalls. “The light changed, the wind died down, and we had a pastoral landscape in front of us.” The miracle, in Elukov’s cosmology, is never divine intervention—it’s a shift in the wind.

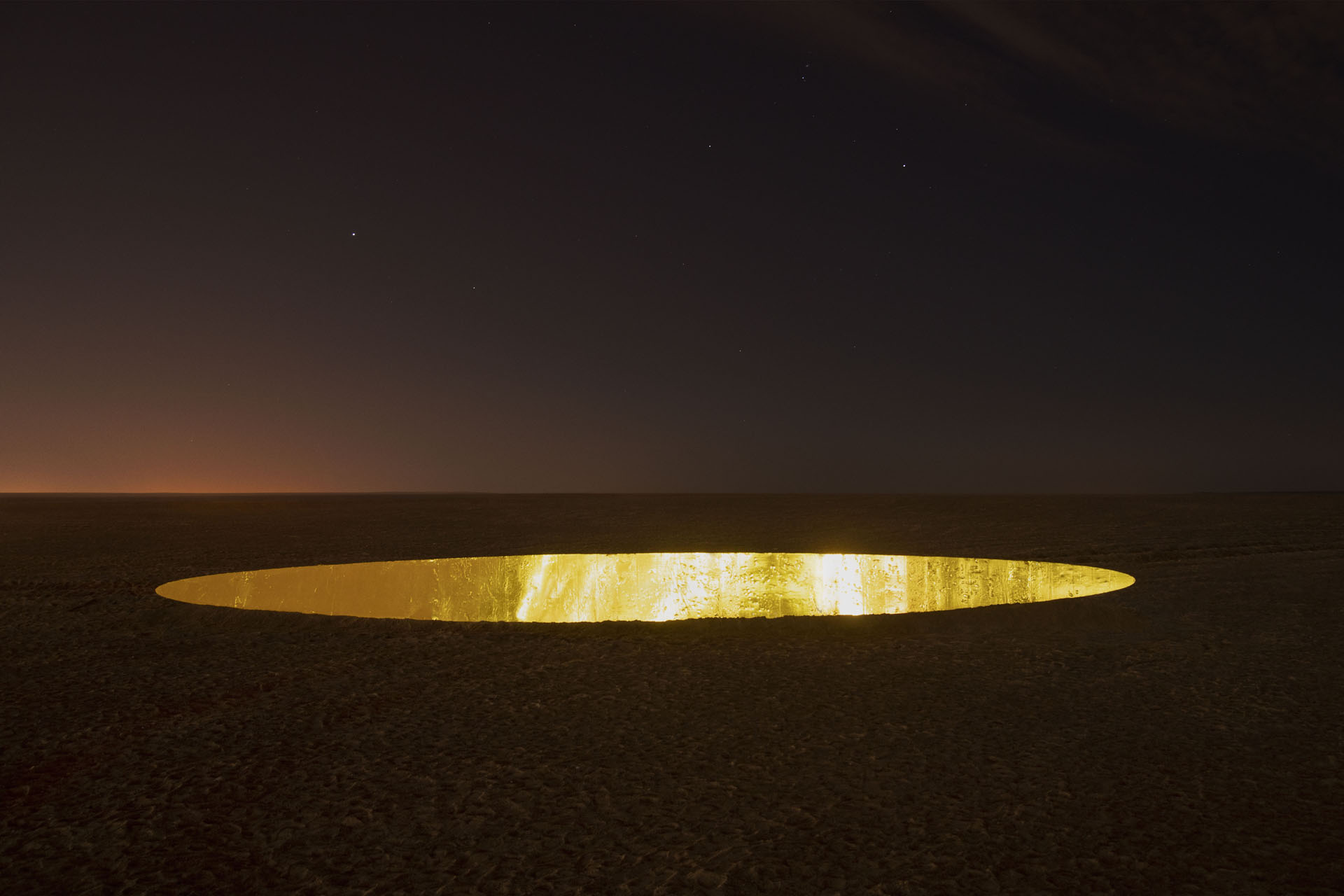

This idea of miracle as meteorological accident connects the series to its 16th-century namesake, the Augsburg Book of Miracles. That manuscript, cataloguing floods, fires, and celestial anomalies, represented divine interference in human affairs. Elukov’s version inverts that premise. “In contrast, I read The Book of Miracles from the position of cosmocentrism,” he writes. “It is a story about forces and elements that are indifferent to us and capable of destroying us; and about the need to seek harmony with these forces.” His miracles are not blessings, but equilibria—moments where destruction and beauty briefly align.

The images form an ecology of symbols: a white stag in a decaying chapel, a ruin half-submerged in still water, a boat aflame under a starless sky, a river of blood coursing through ice. Each one proposes a different kind of genesis story—an aesthetic theology where life and entropy cohabit. The photographs are biblical not because they moralize, but because they evoke awe without explanation.

In their cold, aching grandeur, Elukov’s compositions reject both sentimentality and spectacle. The tundra is not a stage for man’s heroism but a field of cosmic indifference. And yet, there’s tenderness in the persistence of making—hauling cows into the sea, sculpting artificial islands, coaxing light out of inhospitable skies. Elukov’s project becomes, in its devotion and futility alike, a portrait of the artist as a small god: building worlds only to watch them dissolve.

“People cannot fully know everything about the world,” he reflects. “There is no theory that could adequately explain everything.” That unknowability is not a void but a presence—one that hums through every image like a distant frequency. In the Arctic, where horizons and heavens blur, Elukov has found not the end of the world, but its source code.