The collaboration between Nadia Lee Cohen and Martin Parr is a meticulously staged mirage masquerading as suburban memory—a fever dream photo album summoned from the aesthetic debris of late-90s and early-2000s Essex.

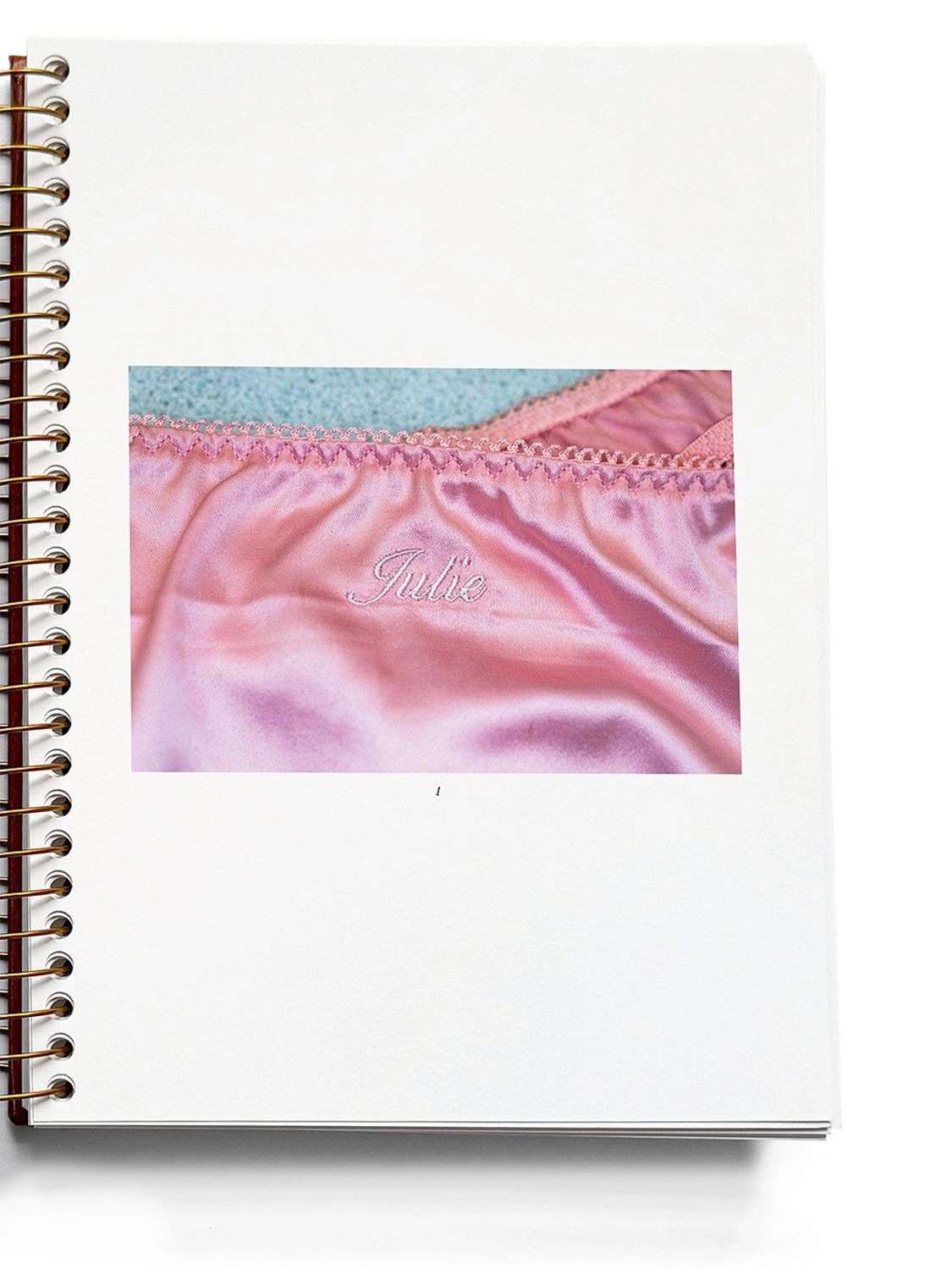

Cohen, in her usual theatre of self-mythologisation, reanimates her childhood babysitter Julie—not as a tribute, but as a prosthetic identity. This Julie is not a person but a platform: a bleach-blonde cipher through which Cohen enacts her fascination with class, glam culture, and the semiotics of femininity. She becomes Julie, but not to honour her—instead, to vivisect the conditions that made Julie visible in the first place.

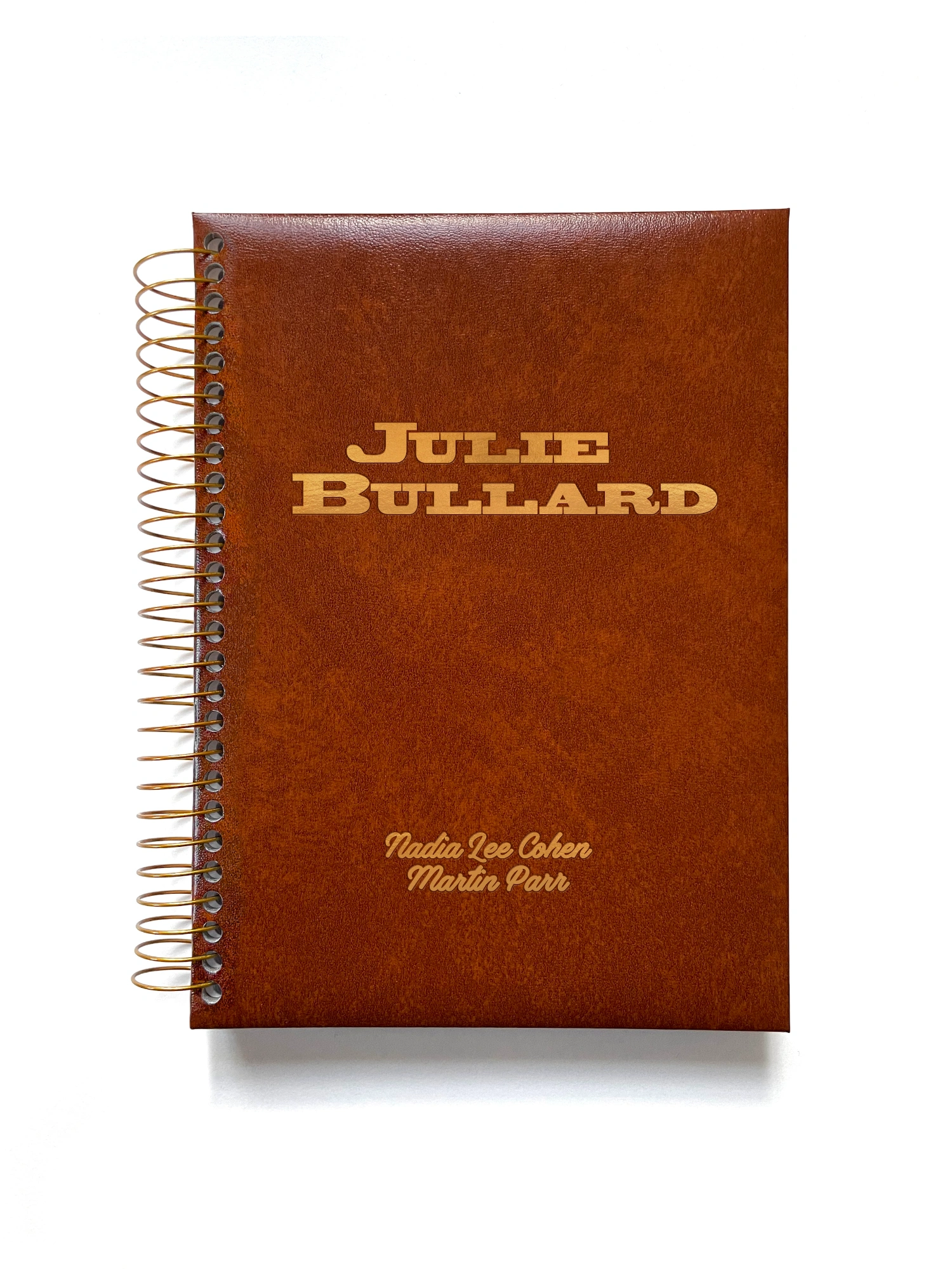

Parr’s role is fascinatingly passive-aggressive. He plays the documentarian, but on Cohen’s set. His images, soaked in that trademark acidic saturation, mimic authenticity even as they stage it. Their faux-naïve album—spiral-bound, found-object cosplay—subtly parodies the British vernacular it purports to emulate. If Parr once captured Britain through a candid, critical lens, here he is a hired hand, refracting Cohen’s vision with eerie compliance.

Cohen’s statement that she’s “trying to visually portray the song ‘Up the Junction’” is revealing. It signals that Julie Bullard isn’t reportage, nor even a fictional biopic—it’s structured like a pop lyric: compressed, confessional, emotionally overexposed. The use of food, Tupperware, Diana kitsch, and soft-focus nationalism does not critique so much as re-stage these tropes with a curatorial tenderness bordering on satire.

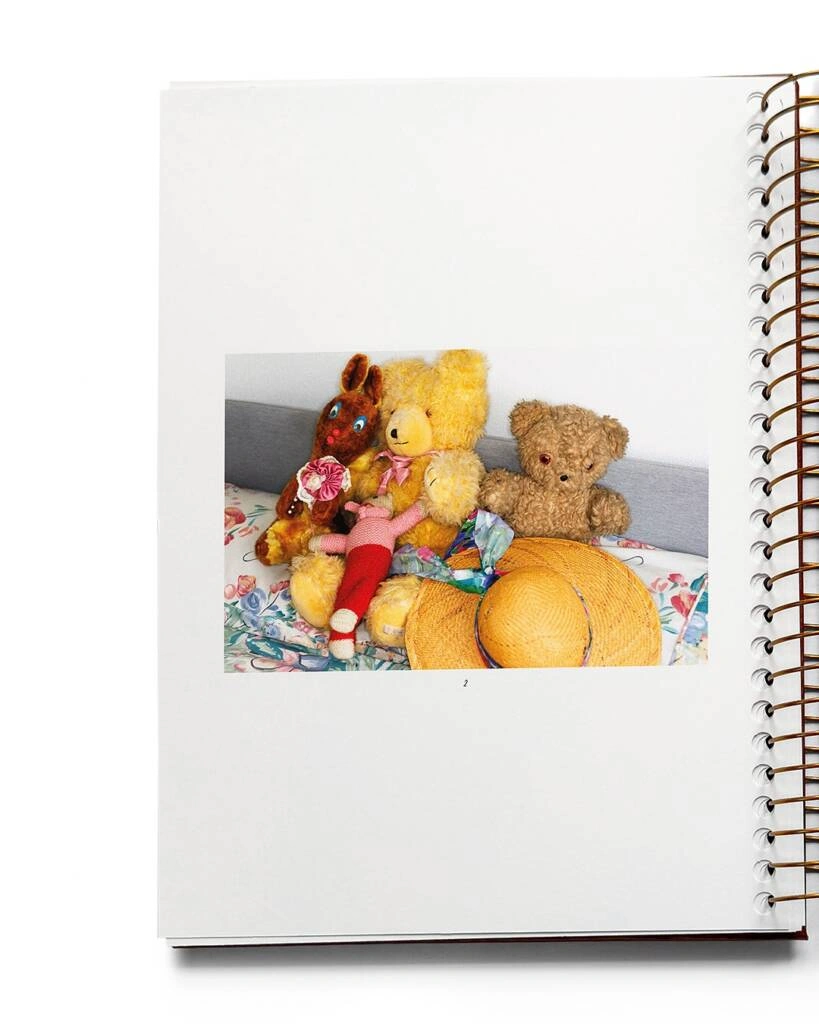

What’s most radical here is the decision to omit Julie’s children, her husband, her “reality.” The absence is political. The album becomes a selective archive, echoing both personal and collective amnesia—where class narratives are retold as aesthetic performances, and working-class womanhood is reimagined as tableau vivant.

Julie Bullard is not a collaboration in the true sense. It’s a carefully choreographed tension between two gazes—Cohen’s maximalist, performative drag of British identity and Parr’s documentary fatigue. The result is a work that queers nostalgia itself, turning memory into mise-en-scène and biography into Baudrillardian theatre. It’s not about who Julie was—it’s about who we were told she could be.