There’s a peculiar ambivalence in sweetness. It charms, it repels. It promises pleasure but suggests decay. For the inaugural exhibition at Sweet World, this duplicity becomes spatial strategy.

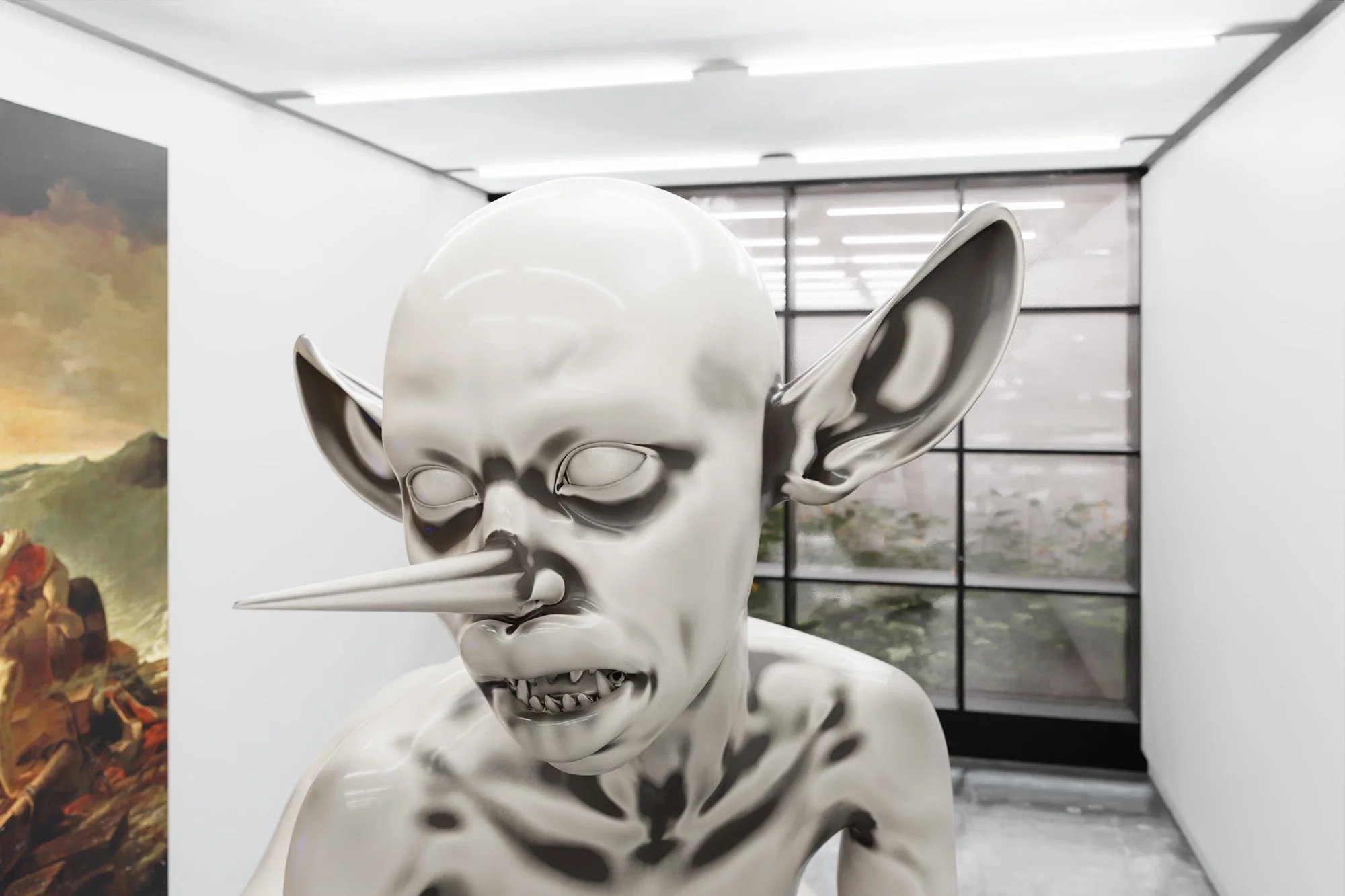

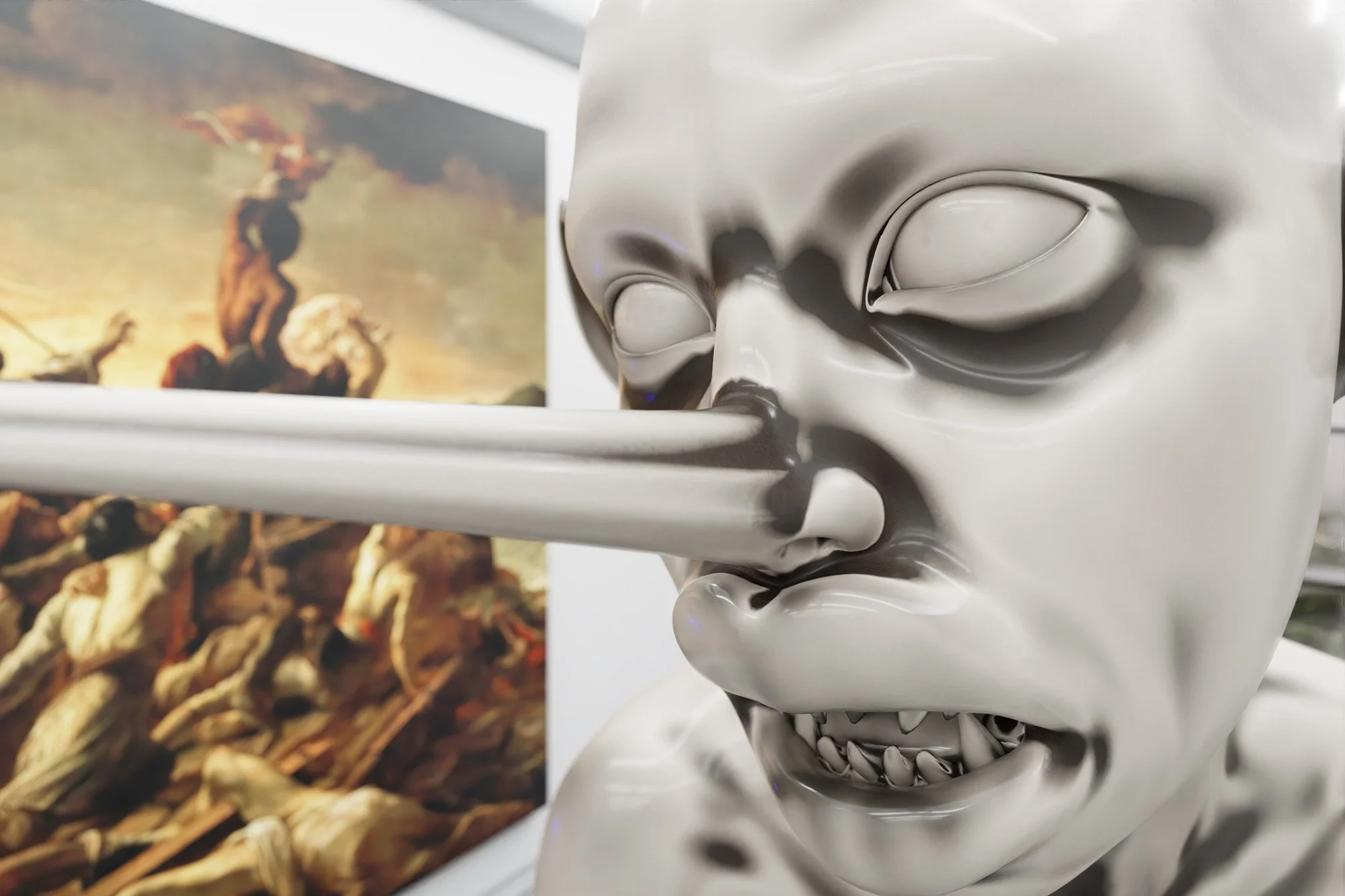

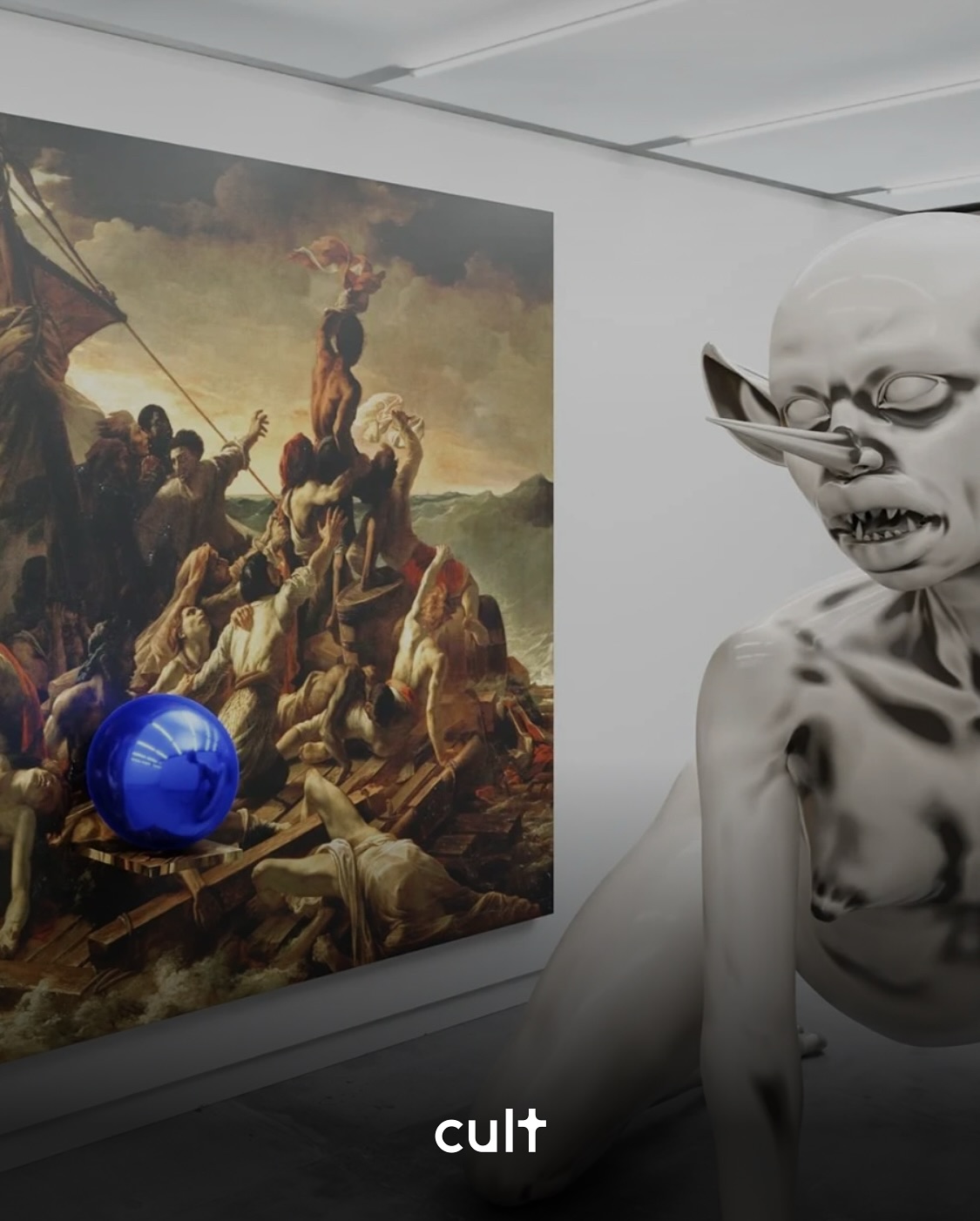

Jeff Koons' canonical Gazing Ball (Raft of the Medusa) is in direct confrontation with Travis John Ficarra's new Chocolate Goblin. Installed in a long, narrow corridor, Ficarra’s sculpture isn't just positioned across from Koons—it blocks him. She doesn't so much invite viewers as halt them.

Previously exhibited at DARKMOFO and Melbourne’s Glasshouse, Ficarra's Goblin returns here with increased force. The artist calls her "more sinister," and the difference is palpable. This iteration is all surface aggression: synthetic gloss, frozen expression, fragments of damage hinted at but not explained. Her presence isn't narrative; it's architectural. "You can't really get around her," Ficarra notes, and he means it literally.

Ficarra works with 3D the way some sculptors work with trauma: indirectly, suggestively, via aesthetic residue. There’s a calculated incoherence to the Goblin, a refusal to be reduced to story. "The ambiguity is more akin to world building than storytelling," Ficarra explains, and that distinction matters. The Goblin isn't a character; she’s an environment. She exerts pressure. She implicates.

This approach finds an uncanny echo in Koons' Gazing Ball series. Both artists, in their own ways, build environments out of seduction—one through mirror-finish allure, the other through corrupted cuteness. Yet the tension isn’t merely visual; it’s ethical. What are we drawn to, and why? What does it mean to be lured?

Ficarra's sculpture feels haunted by a post-Internet visual language: plasticity, glitches, synthetic nostalgia. “I'm attracted to something like a plastic toy that has grime and scratches, worn scuff marks, or like sickly candy, a rotting cake,” he says. The Goblin is both commodity and corpse, a residue of something once consumable. Her gloss is a trap.

And then there’s the question of violence. Not overt, but structural. "There is a constant tension between conflicting elements: fantasy and reality, a glossy slickness and a grime or rot," Ficarra says. This isn’t violence as spectacle, but violence as structure. The sweetness here wounds by design. The Goblin seduces to hold you still.

That stillness—that enforced pause—is the show’s masterstroke. You can't see Koons without confronting Ficarra. It's a kind of relational dramaturgy: the old regime of reflective spectacle meets the glitchy, uncanny now. One is iconic; the other infects. You come for Koons, but you stay with the Goblin. Or maybe she stays with you.