Most Dismal Swamp’s latest incursion into the porous boundary between world-building and world-decay arrives at The Bacon Factory like a cryptic dispatch from a future already exhausted with itself. The Bastard Fields—co-commissioned by Autotelic Foundation and curated by Nadim Samman—doesn’t posture toward prophecy. It behaves more like a leaked file: unstable, malware-ridden, feral in its logic. It’s the kind of work that doesn’t just show you a landscape; it corrupts your operating system.

Walking into the installation feels like stepping into a bunker converted into a livestream studio by a cult with no clear doctrine. Screens alternate between synthetic vistas and sodden Scottish bogs, the latter tied to the Covenanters—17th-century dissenters hiding in caves to practice belief without punishment. Their legacy mutates here into a metaphor for contemporary “safe spaces” under siege. As Dane Sutherland notes, the bog becomes both terrain and interface: “a screen for what they believed in.” In the film, bodies don’t disappear into the earth; they pixelate into it.

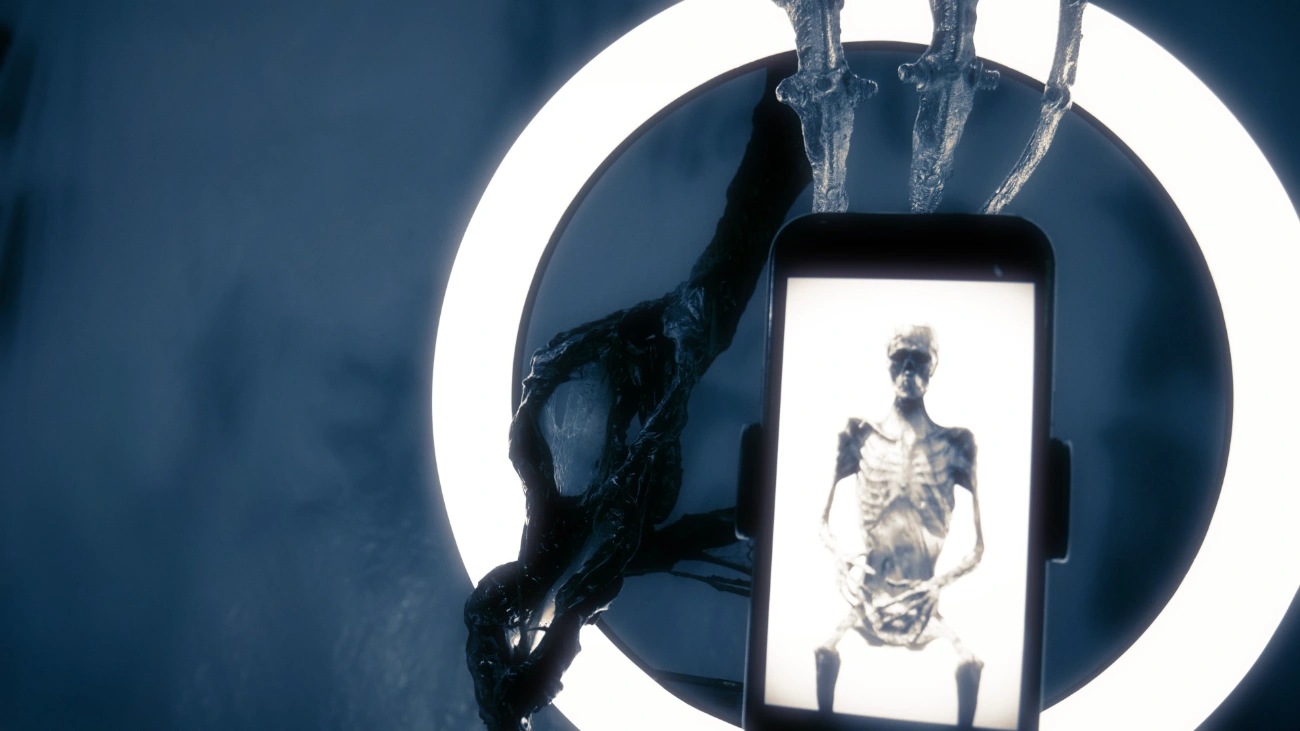

The narrative—if one should call it that—is a cycle of collapse. A bog-body skeleton trudges through a weather-blasted landscape, edging toward the mechanical replacement waiting in a cave: a robot in activewear with exposed gears and the weary poise of someone forced to tutorialize the singularity. “Submit to the singularity,” it instructs, before the image ruptures and the sound “of something unnecessary intensifies.” The film loops, as if insisting that the collapse is not a finale but a climate.

Within the installation, fragments of this fevered ecology materialize: a mannequin slumped on a couch, face replaced by a jittering mechanical jaw; a coffin holding a fox-masked figure suspended between satire and sacrifice; panels of glitched iconography lining the walls like devotional screens for a digital monastic order. Everything is half-real, half-rendered, refusing the security of full embodiment. It mirrors the film’s “model collapse,” in which AI systems, trained on synthetic data, begin producing reality by hallucinating it.

This is where Most Dismal Swamp’s world hits uncomfortably close. The sermonizing figure in a decaying cloth mask—part medieval penitent, part unhinged influencer—could be “a reflection of Society’s veneration of influencers peddling warped views,” or simply a person forced into hiding for expressing the wrong thing at the wrong time. The ambiguity isn’t a twist; it’s the point. In this universe, truth behaves like a contaminated water table: whatever emerges has already been compromised.

The skeletal wanderer—humanity as residue—moves through cliffs and mist while a discordant guitar scrapes the edges of the frame. These outdoor shots aren’t pastoral; they’re drenched in a mournful hostility. You sense the terrain rejecting its occupant. And yet, there’s a strange tenderness in watching this creature persist, as though searching for a version of itself that hasn’t been overwritten.

What The Bastard Fields ultimately stages is not dystopia but midification—a term the collective uses to describe reality’s slide into a flattened, MIDI-like domain where nuance is lost, and everything becomes programmable, repeatable, deniable. This isn’t a world where AI takes over; it’s one where the line between cultural memory and computational hallucination dissolves.

The film ends on a biblical provocation: “As a dog returns to its vomit. So a fool returns to its foolishness.” It lands less as moral judgment than as an exhausted sigh. The loop continues, the model collapses, and the swamp—literal, digital, historical—absorbs what’s left.