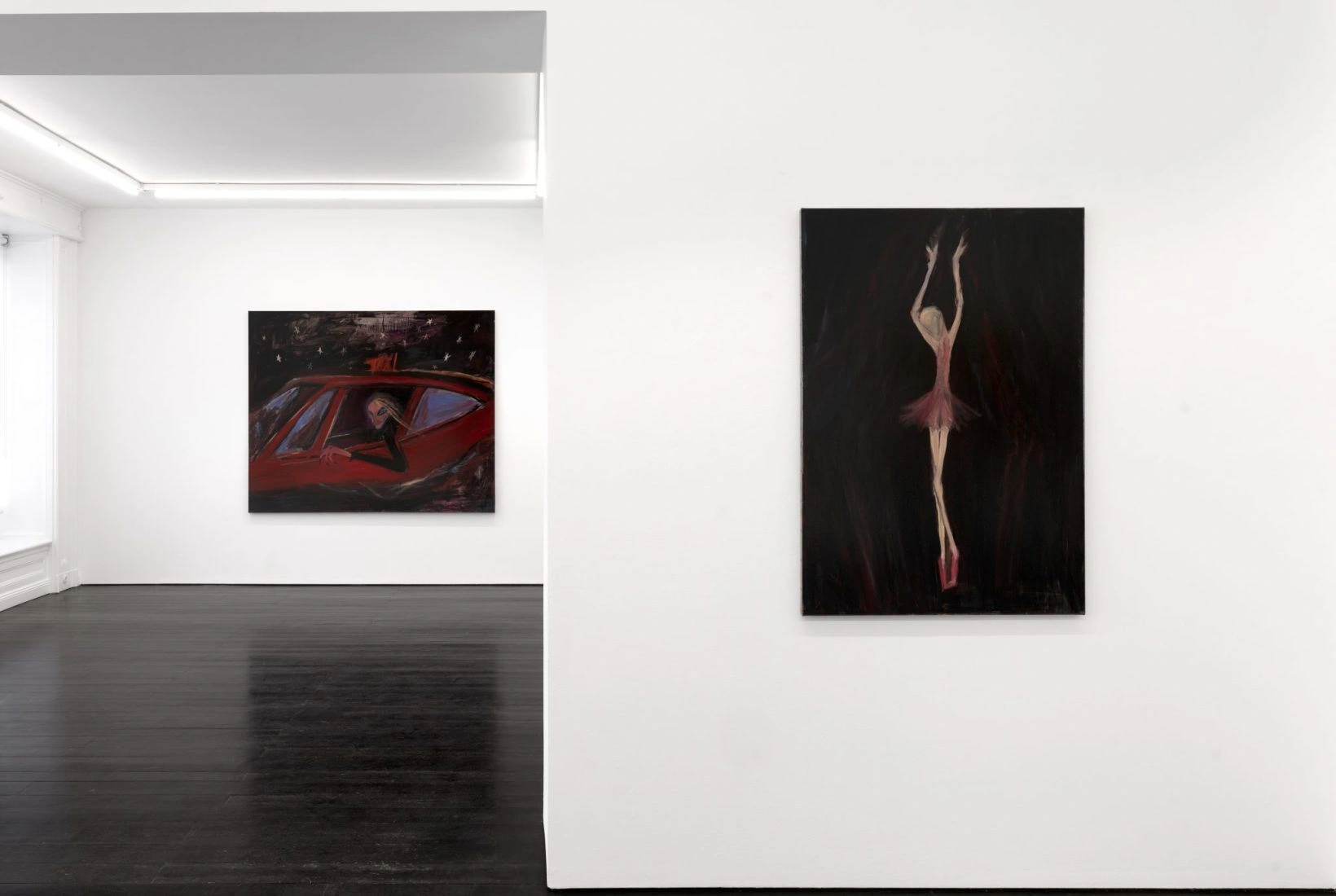

On the surface, Tobias Spichtig’s Taxi zur Kunst, currently on view at Contemporary Fine Arts in Berlin, is an homage to painting. But to reduce it to reverence would be to miss the deeper hauntings and provocations embedded in his third solo exhibition with CFA. Spichtig isn’t just flirting with art history—he's undoing its categories from within, using the group portrait not as a celebration of community, but as an excavation of distance, alienation, and the spectral machinery of sociality.

The title Taxi zur Kunst began as a joke. A glib phrase. An empty slogan that Spichtig had long wanted to see printed on the back cover of Texte zur Kunst, the very page where CFA has held ad space for years. It’s a phrase that teeters between irony and sincerity—exactly where Spichtig’s work thrives. The taxi: a space of movement, transition, blurred windows, and anticipated arrivals. It's a vehicle of passage, not presence. And this is how painting functions for Spichtig—as a nostalgic act, yes, but not one rooted in sentiment. For him, nostalgia is not recollection. It is a drive. A distorted impulse toward a past that never fully existed. A longing for a known thing that refuses to cohere.

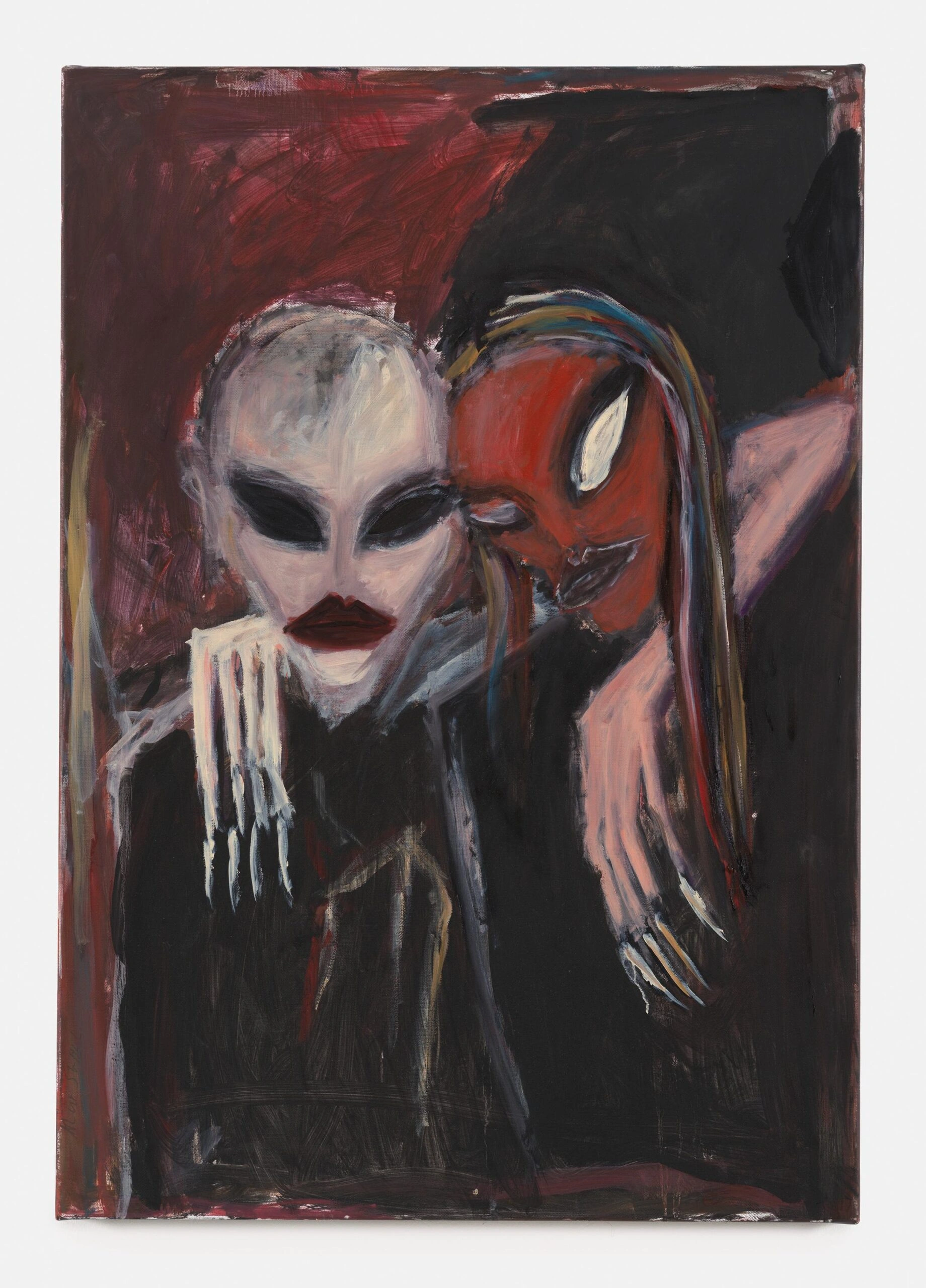

Taxi zur Kunst marks Spichtig’s embrace of the group portrait—a canonical genre typically used to affirm identity, capture likeness, and render belonging. But here, groupings become estrangements. People appear as outlines, almost hastily rendered, their bodies angular and oddly pointed, slipping into mannerism. Black—thick, insistent—contours everything. It suffuses the canvas, bleeds into detail, anchors the gaze in a kind of chromatic deadlock. The muses’ eyes—oversized, dark, hollowed out—refuse intimacy. They confront the viewer like accusations or voids. The references to Spichtig’s earlier “sunglasses paintings” are not incidental. There, too, one sought a reflection that never came. Here, again, vision is unrequited.

If Spichtig’s figures recall Bernard Buffet’s grim stylization or the raw outlines of German Expressionism—particularly Kirchner’s sinewy lines—it’s not out of historical mimicry, but because his work channels a parallel urgency. As the Weimar years danced at the edge of collapse, so do we now navigate a culture of soft crisis, desperate frivolity, and ambient dread. In this sense, Spichtig's paintings are not nostalgic—they're diagnostic. They capture the tonal texture of our present: theatrical, overexposed, and terminally exhausted.

Yet Spichtig calls himself a realist. And here is where the paradox intensifies. His portraits are not imagined; they are documentation. These are friends, lovers, collaborators—the cast of his own nightlife, his own dinners, the spontaneous theatres of social life. In this, he mirrors Warhol not just in aesthetic detachment, but in the deeply personal act of curation. The people in his paintings are muses, but also mirrors. They are present in their abstraction, intimate in their anonymization.

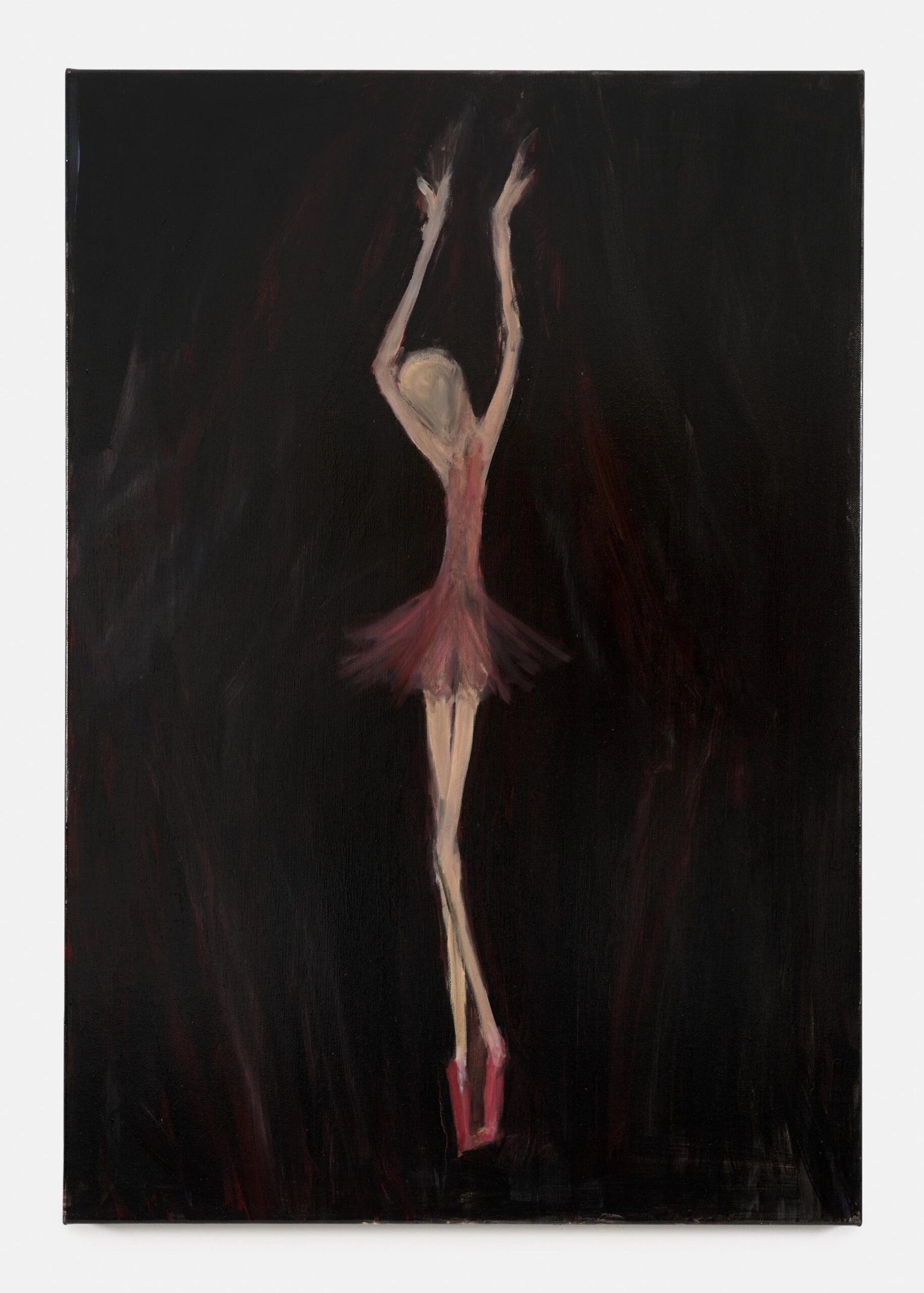

Each canvas could be read as a loose narrative: a driver waits, someone kisses someone else, a dancer hunches toward sleep, a band poses, a crowd dissipates. These fragments evoke the murmur of a scene—the cultural infrastructure of Berlin itself, seen not as grand event but as low-grade drift. But the narrative never fully forms. It collapses into symbol, gesture, metaphor. Spichtig is not telling stories. He is circling moods. And in doing so, he finds the existential edge of painting itself.

Indeed, his aesthetic operates in a dialectic: embarrassment and seriousness, humor and melancholy, presence and loss. The paintings hang in this tension, daring the viewer to meet them without resolving them. The nudes, in particular, are especially striking—bodies neither male nor female, neither sensual nor clinical, situated in multilayered fields of color that pulse with psychic intensity. They repel the voyeur even as they beg to be seen. They are both spectacle and refusal.

Spichtig’s understanding of the political is not didactic, but structural. His paintings are political in their refusal—in their resistance to clarity, resolution, and the instrumentalization of identity. This is not protest art, nor is it apolitical. It is art that dislocates. Art that withholds. In the space of refusal, Spichtig claims the right to seek beauty—but a beauty laced with futility, irony, and the embarrassment of still caring.

In conversation, Spichtig speaks of beauty as something to be pursued in full awareness of its own collapse. This is the ambition of Taxi zur Kunst: to move toward beauty while knowing it is already compromised. The taxi is a vessel of this ambivalence. It takes you nowhere new. It merely ushers you toward repetition, arrival, and the shimmer of meaning at the edge of disappearance.

Spichtig’s exhibition, like his wider oeuvre, is not about arriving at art. It is about the drive—the strange, spectral process of moving through images, through people, through nights that may or may not have mattered. What he offers us is not closure, but a question: who is in this taxi with us, and where exactly are we going?