In Beyond the Lake, Carlos Folgoso Sueiro returns to Galicia not as a son reclaiming home, but as a witness to its quiet unraveling.

His images—of drowned villages, charred forests, and solitary figures—are less documentary than dream. They move between the spectral and the real, like memories resurfacing from beneath a lake. “We are the result of our past,” he declares, and the phrase becomes both diagnosis and mantra, an understanding that history is never buried—it only sinks, waiting for drought to bring it back to the surface.

What Folgoso Sueiro finds upon his return is a landscape at war with itself. Once a lush refuge on Spain’s Atlantic edge, Galicia now bears the scars of industrial progress and ecological collapse: eucalyptus plantations replacing native forests, dams erasing villages, and rural communities hollowed out by emigration. The photographer had spent a decade abroad, documenting other people’s crises, until personal loss and injury pulled him back to the fractured soil of his childhood. His camera, once a tool of reportage, became a mirror for his own melancholy. “I understood that I was shooting my own melancholy,” he admits.

This melancholy is not passive. In the dim light of his compositions—half Rembrandt chiaroscuro, half Tarkovskian fog—there’s a resistance to disappearance. The flooded village of Aceredo, emerging ghostlike from the Lindoso reservoir during a period of drought, becomes a central metaphor: the drowned past gasping for air. These ruins are not monuments but living wounds, their exposed walls testifying to a nation’s uneasy pact with modernity. “I connected to this place,” Folgoso Sueiro recalls, “I felt as if something was waiting for me there.”

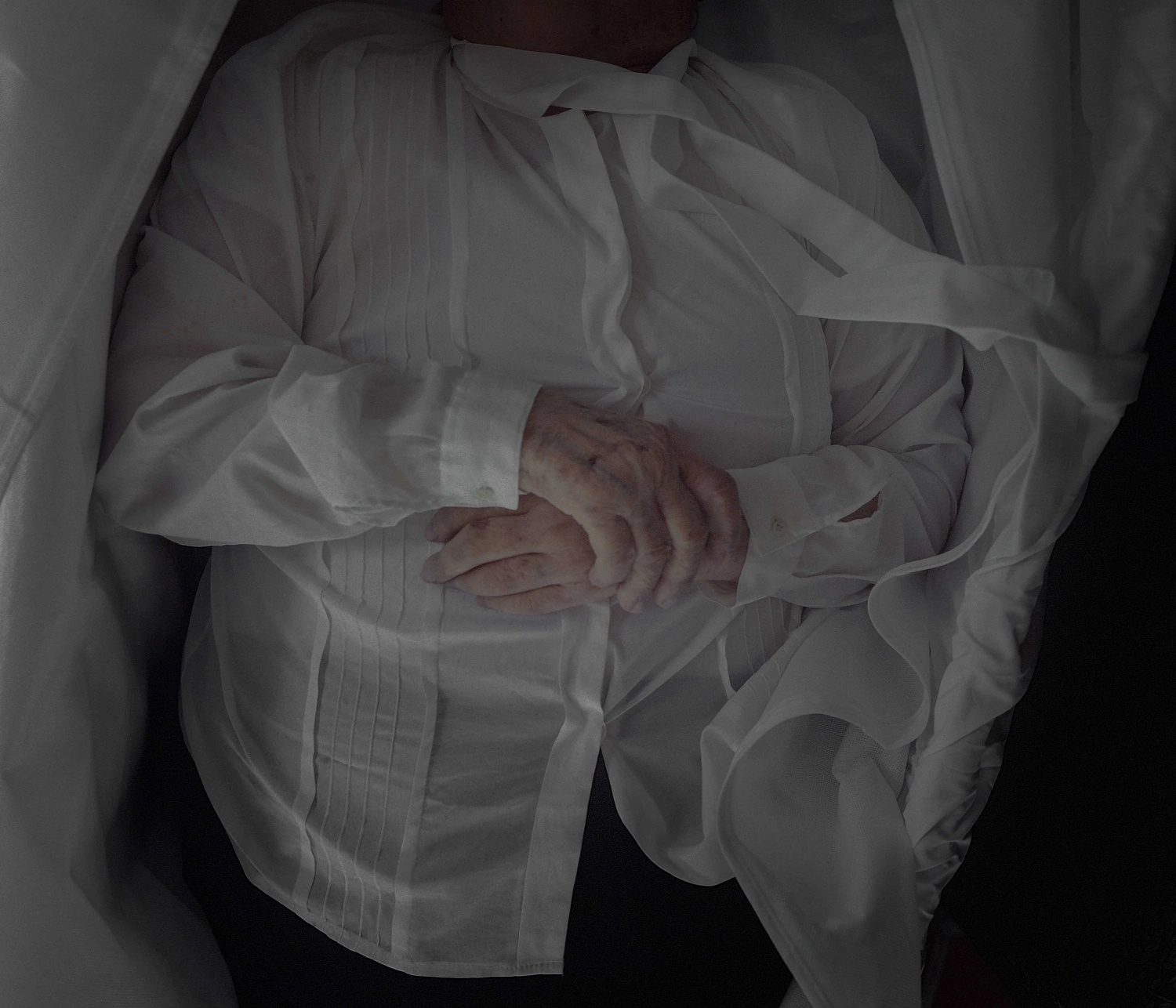

His subjects—farmers, wanderers, the elderly, those left behind—inhabit the photographs like characters from a rural mythology rewritten under climate collapse. Adolfo and Raúl, a couple ostracized by their community, stand in the wreckage of a burned home, their faces lit by a thin mercy. María, who emigrated decades earlier and left her son behind, is remembered through Emilio, whose struggle with alcoholism becomes a parable of generational grief. “My family is Galicia. This flooded place is Galicia. This forest fire is Galicia,” Folgoso Sueiro insists, collapsing the distance between biography and landscape.

If Beyond the Lake feels cinematic, it’s because it stages the rural as both site and psyche. Folgoso Sueiro borrows from the syntax of film—slow pacing, long takes, suspended time—but uses it to compose a portrait of erosion. Each frame contains an echo: the sound of rain striking a reservoir, the low hum of an abandoned power line. What emerges is not nostalgia but something closer to animism, a belief that every object—stone, water, ash—retains consciousness.

Against the myth of progress, Beyond the Lake offers an ethics of slowness, of attention. It is an elegy, but also a reclamation. Through his lens, Galicia’s decay becomes a kind of knowledge: how to live amid loss, how to see beauty in persistence. In the end, Folgoso Sueiro does not resurrect a vanished homeland; he learns to coexist with its ghosts.