There's something deeply unsettling about entering a church where LED screens have replaced stained glass, where "algorithmic semiogenesis" meets centuries-old liturgy. Yet in Philipp Timischl's Dummodo me ames at St. Andrew's Church in Salzburg, this collision feels less like sacrilege than revelation—a mirror held up to our current moment where devotion has migrated from pews to pixels, from hymns to hashtags.

The exhibition's title, translating to "as long as you love me," operates on multiple frequencies. It's a fragment of 17th-century Latin ecclesiastical performance, yes, but also unmistakably echoes Justin Bieber's 2012 teen-pop anthem. This isn't mere irony; it's Timischl's way of acknowledging that contemporary longing—whether directed toward the divine or the digitally mediated beloved—shares the same grammar of desperate attachment.

Upon entering the sacred space, visitors encounter what can only be described as a digital transubstantiation. An LED intervention frames the traditional altar through "a cruciform void," transforming the church's architectural certainties into something more tentative, more flickering. The machine-generated landscapes that populate these screens—"liminal topographies, unstable environments, ontologically ambivalent terrains"—suggest not the firm ground of faith but the vertiginous scroll of an infinite feed.

Perhaps the exhibition's most arresting moment occurs in a side chapel, where a "computationally orchestrated raccoon choir" periodically emerges to perform. The absurdity is intentional, yet there's something genuinely moving about these digital creatures attempting song—a "paradoxical sincerity" that captures how we now seek meaning through screens, finding the sublime in the ridiculous, the sacred in the synthetic.

Throughout the nave, freestanding LED sculptures wrapped in "ornamental referents evocative of bourgeois domesticity" create an uncanny domestication of the divine. These pieces, hovering between liturgical apparatus and interior design, expose how class aesthetics have always infiltrated spaces of worship—from gilded altarpieces funded by merchant families to today's megachurch LED walls.

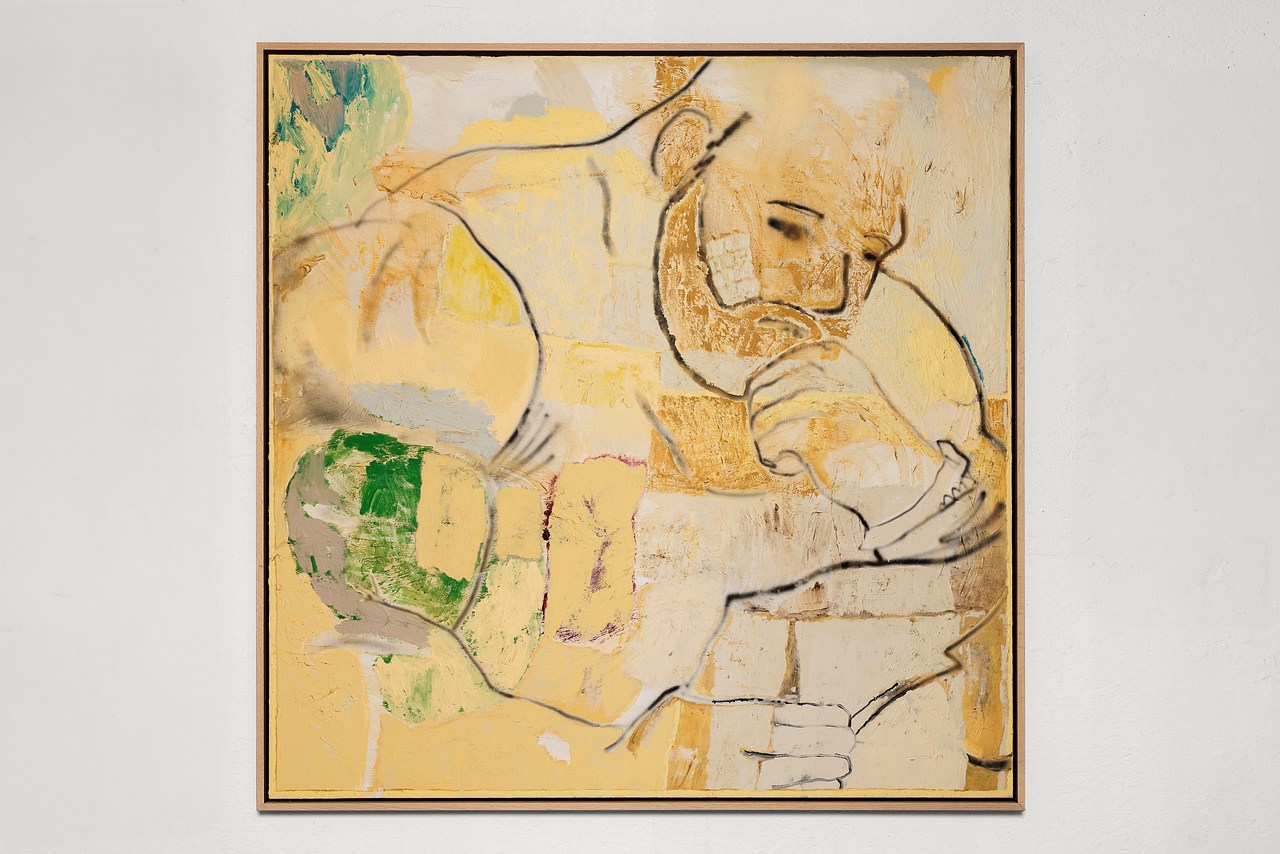

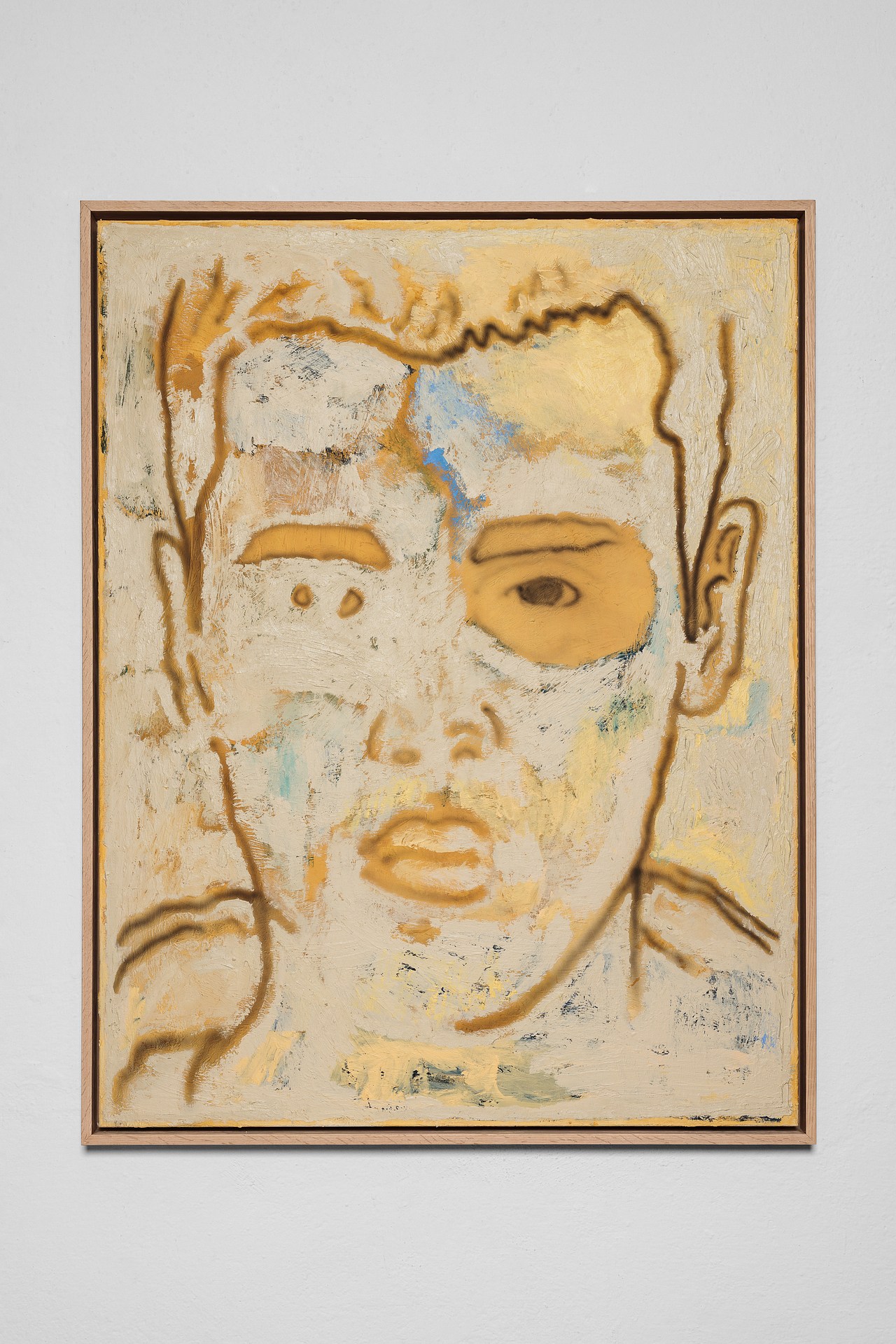

One particularly haunting work features a painted male figure, "bearded, muscular, contemplative," whose pen hovers at the intersection of canvas and screen. This frozen gesture articulates our current crisis of authorship—who creates when the algorithm assists? Where does human intention end and machinic generation begin? The figure's suspended action becomes a metaphor for artistic agency in an age of AI collaboration.

What makes Dummodo me ames compelling isn't its critique of digital culture's incursion into sacred space—that would be too easy, too expected. Instead, Timischl proposes something more radical: that our "machinic spirituality" might constitute its own form of genuine devotion. The exhibition "eschews parody in favor of a sincere reinvestment in the forms of belief," suggesting that even our mediated, algorithmic attempts at connection contain authentic longing.

Philipp Timischl’s work suggests that perhaps the divine has simply migrated, finding new hosts in our endless feeds, our failed uploads, our desperate digital prayers for connection. "Scrolling like a feed, resonating like a hymn, and looping like a failed upload," the exhibition doesn't mourn the loss of traditional spirituality but asks: what if this is simply what transcendence looks like now?