Amidst the shrill anxieties of late capitalism and the synthetic myths of Silicon Valley futurism, Murray Ballard’s photographic project The Prospect of Immortality emerges not as documentation but as a metaphysical autopsy of our desire to outlive ourselves.

For nine years, Ballard infiltrated the uncanny habitats of cryonics culture—a community dispersed between Peacehaven’s pensioner calm and the technocratic sterility of Arizona’s Alcor labs, all the way to KrioRus’ makeshift facilities on Moscow’s decaying fringes.

Inspired by Robert Ettinger’s 1962 book of the same name, Ballard’s title is no coincidence. Ettinger’s work wasn’t just speculative—it was a manifesto. A promise that death could, perhaps, be deferred, paused in nitrogen, made administrable. “I think cryonics is a fascinating and extraordinary idea and provokes all sorts of questions about the future of humanity,” Ballard reflects. But his images do not evangelize. They observe. They hover. They mourn.

What begins as curiosity slowly disassembles the techno-utopian delusion. In Ballard’s lens, cryonics isn’t the glossy futurism of a TED Talk—it’s a cardboard box lined with foil. A nurse adjusting IV fluids over a gurney-capsule hybrid. A tank marked АЗОТ ОПАСНО—"Nitrogen, Danger”—cradled in duct tape and held together with a dream. This is the material unconscious of immortality, the backstage of eternity.

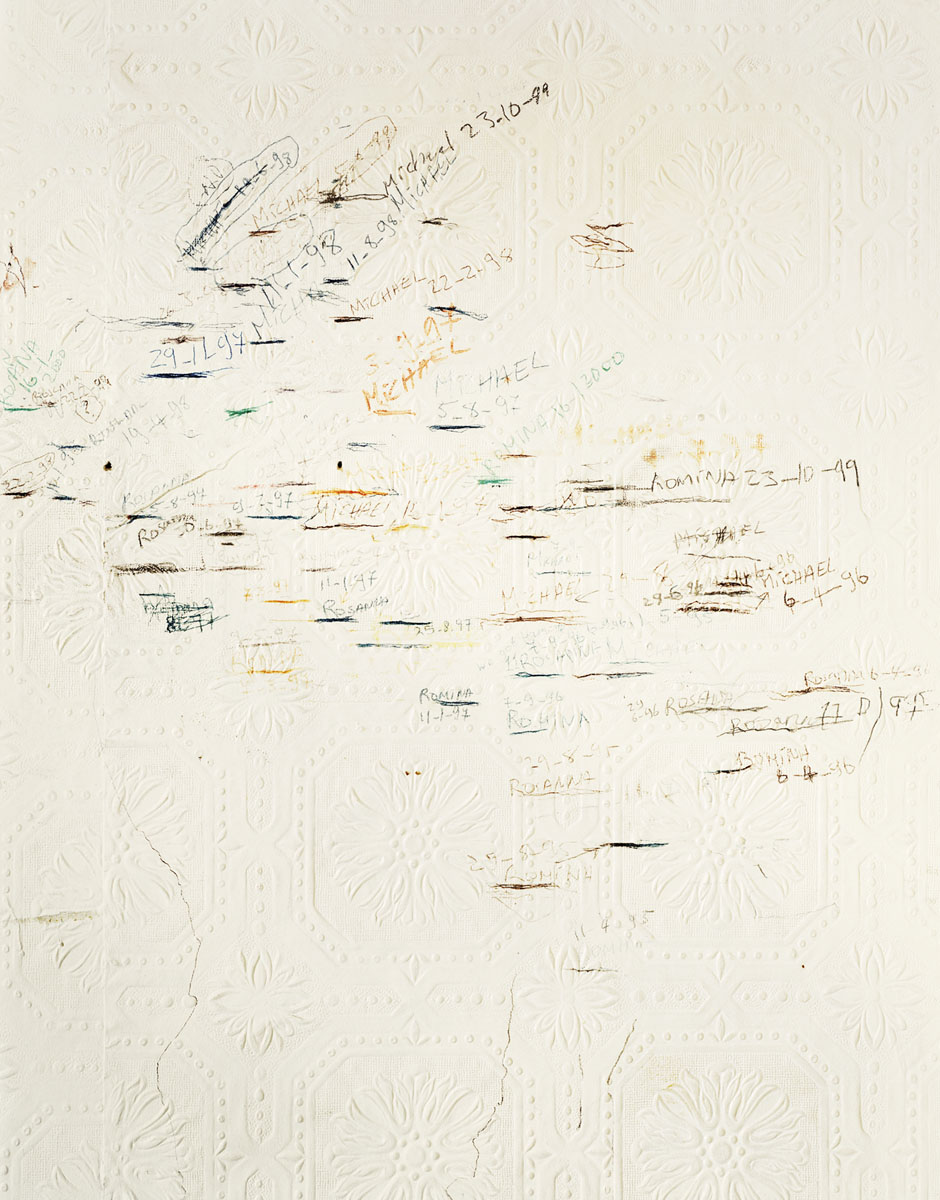

Ballard’s use of large-format 5x4 film pushes the viewer into a mode of deceleration. The stillness isn’t peaceful; it’s forensic. Each detail—the lace of a pillow in a frostbitten cryo-bed, the Soviet-era fan heater warming a body just moments from deep-freeze—becomes an index of the absurd intimacy between life, death, and the cold promise of scientific resurrection.

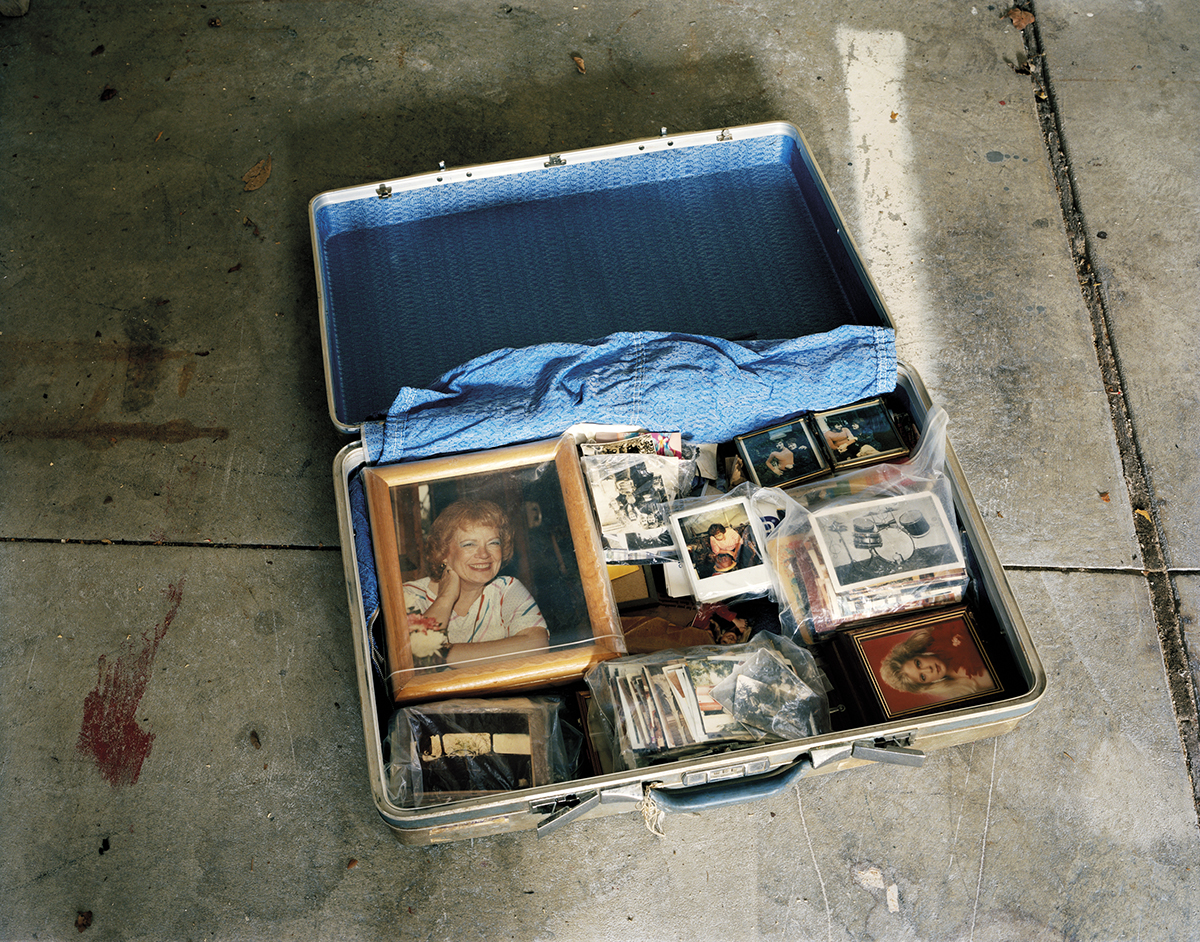

We are asked not to judge, but to linger. “There’s an incredible optimism signing up to cryonics, which I admire,” Ballard says. And this optimism—the absurd, sublime, quasi-religious kind—is etched into the faces of his subjects. Their portraits hang onthe wall, as if to reassure the viewer: we are human. We hope.

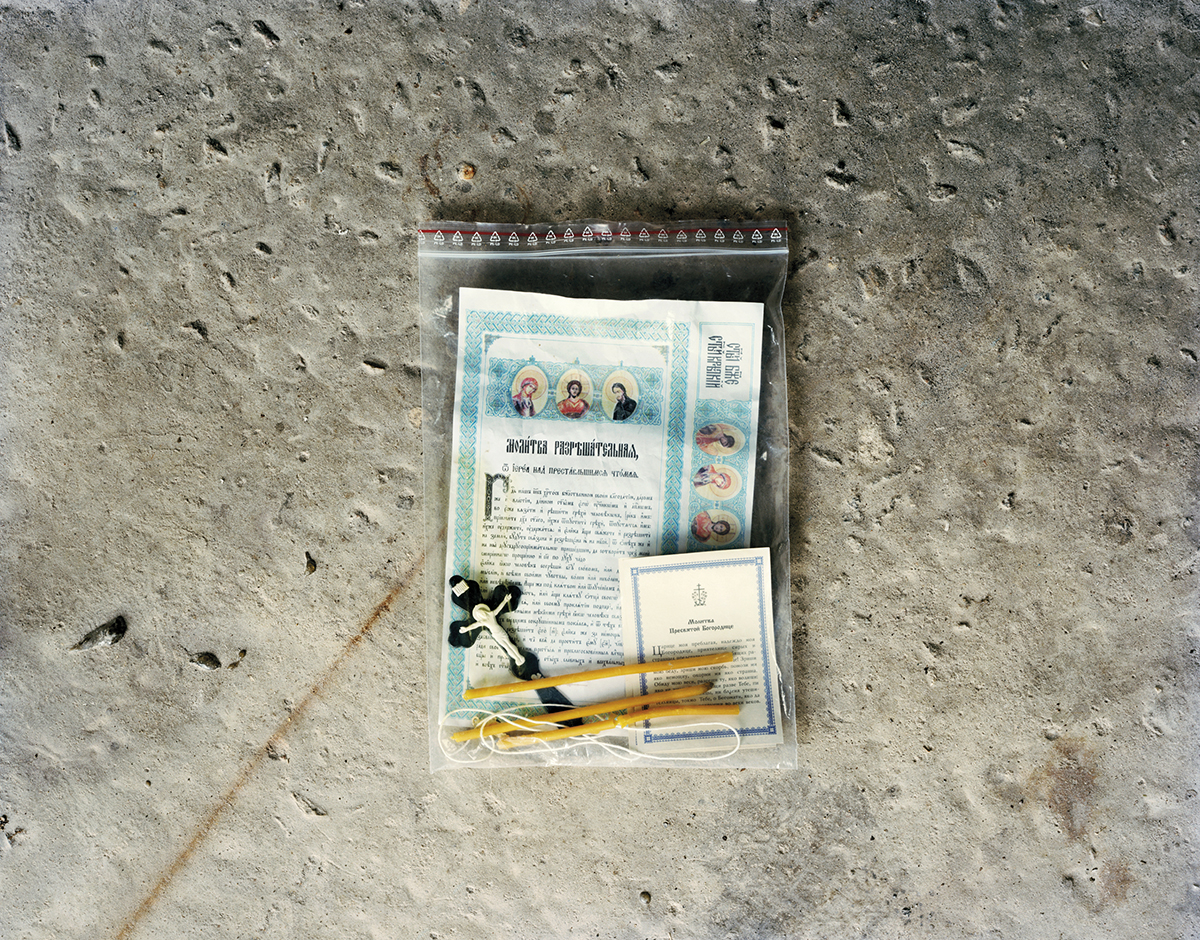

Yet the hope here is taut with melancholy. The Prospect of Immortality refuses to offer answers—it quietly implodes the binary between delusion and devotion. The frozen bodies aren’t just awaiting revival; they’re already narrating a new mythos of what it means to be human in the 21st century. In a secular world increasingly governed by techno-capital and post-truth politics, cryonics becomes not just a science, but a ritual—a last-ditch attempt at ontological control.

Ballard’s work reads like a visual theology of transhumanist longing. It occupies the strange space between speculative science and spiritual performance. In one image, a plastic ziplock bag holds Orthodox prayer cards and a crucifix. In another, we see the barren Russian landscape where hope and entropy intersect, and a woman—coated in snowlight—stands at the edge of a future that never quite arrives.

What makes The Prospect of Immortality truly unsettling isn’t its grotesquerie, but its restraint. There is no shock, no post-apocalyptic theatrics—only the eerie mundanity of preparing for a life that might, somehow, resume. These aren't portraits of death, but of waiting.

Ballard’s cryonic landscapes are contemporary memento mori—reminders not of mortality, but of the lengths we will go to deny it. In the freeze-frame silence of these photographs, time stretches and collapses. The present becomes a placeholder. And the future? A refrigerated archive of ambition, tenderness, and delusion.