The figures lie prone on institutional tile floors, their animal-print costumes—leopard, giraffe—suggesting a grotesque domestication of the wild, or perhaps a return to it, though which direction constitutes return remains deliberately unclear. Joseph Klahr's Public Life Subscriptions, on view at Leroy's Los Angeles through January 10, 2026, assembles itself as a dark meditation on public complicity, institutional violence, and the peculiar moral architecture through which societies manage their own cruelty.

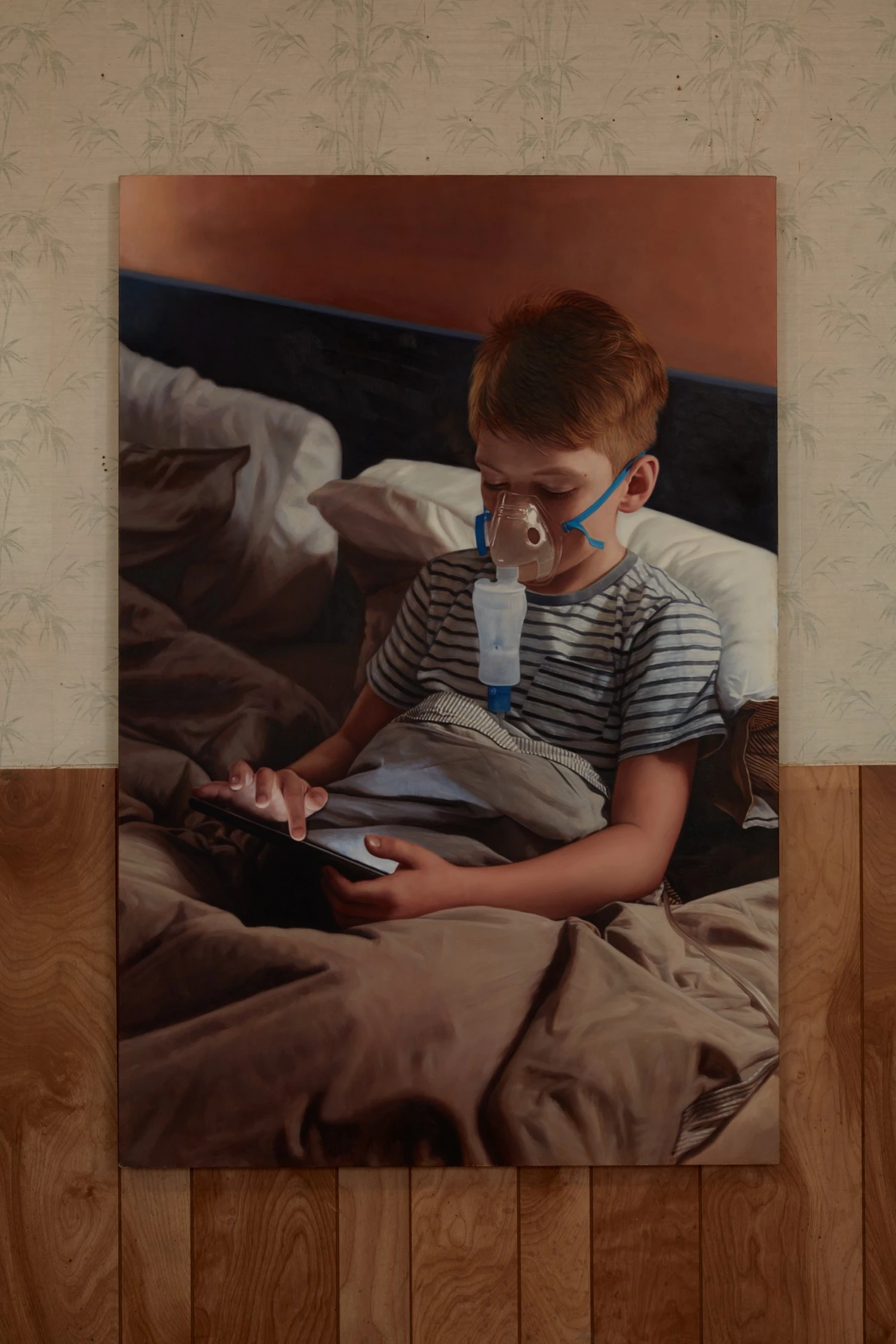

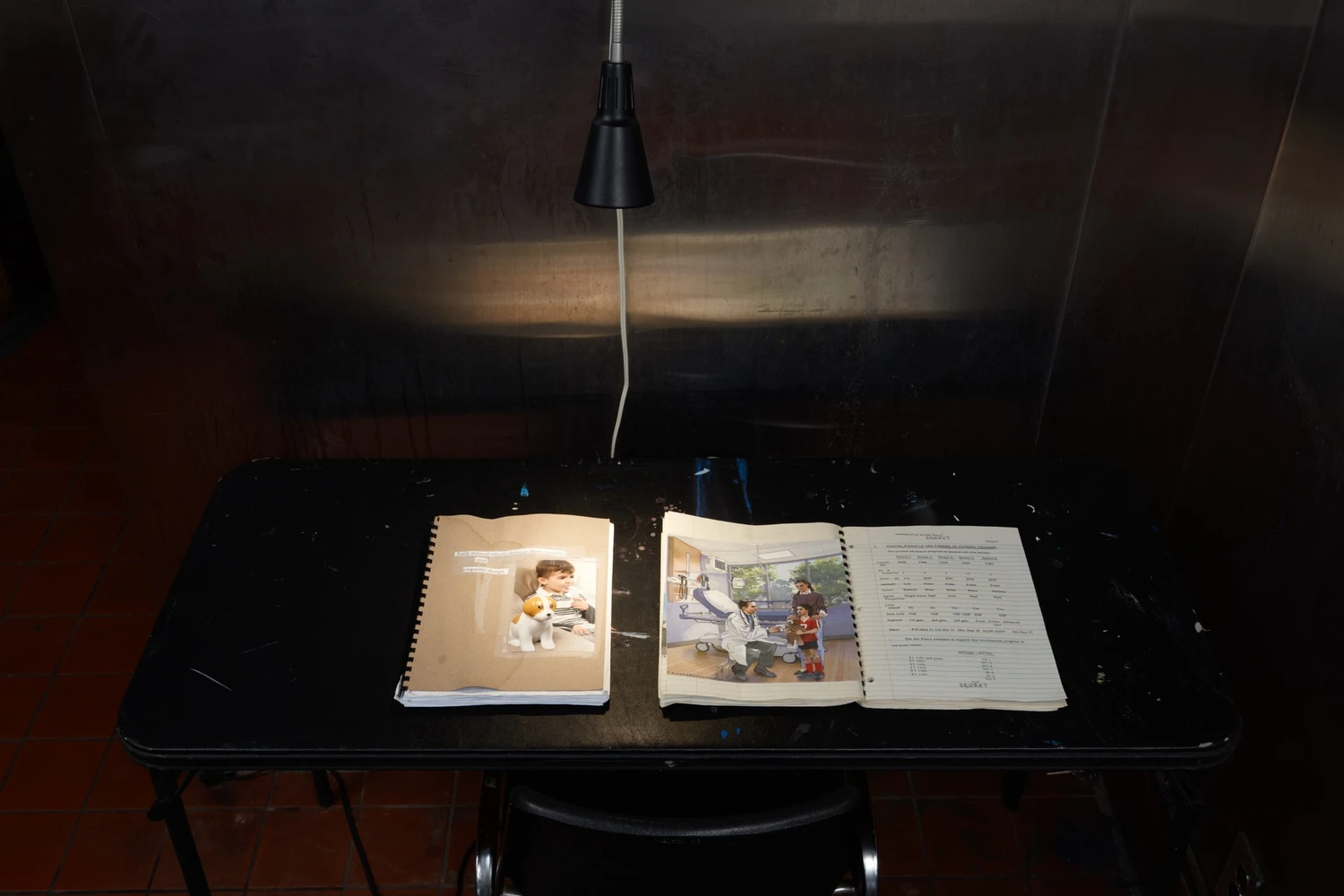

The exhibition begins with an epigraph from Robert Cleaver and John Dod's 1621 Godly Form of Household Government, a text consumed with the child's innate corruption and the parent's sacred duty to correct it. This is not ancient history; it is the template through which institutional violence perpetuates itself. The child must be shaped, reformed, corrected. The family becomes the model for all subsequent institutions—the school, the laboratory, the state apparatus itself.

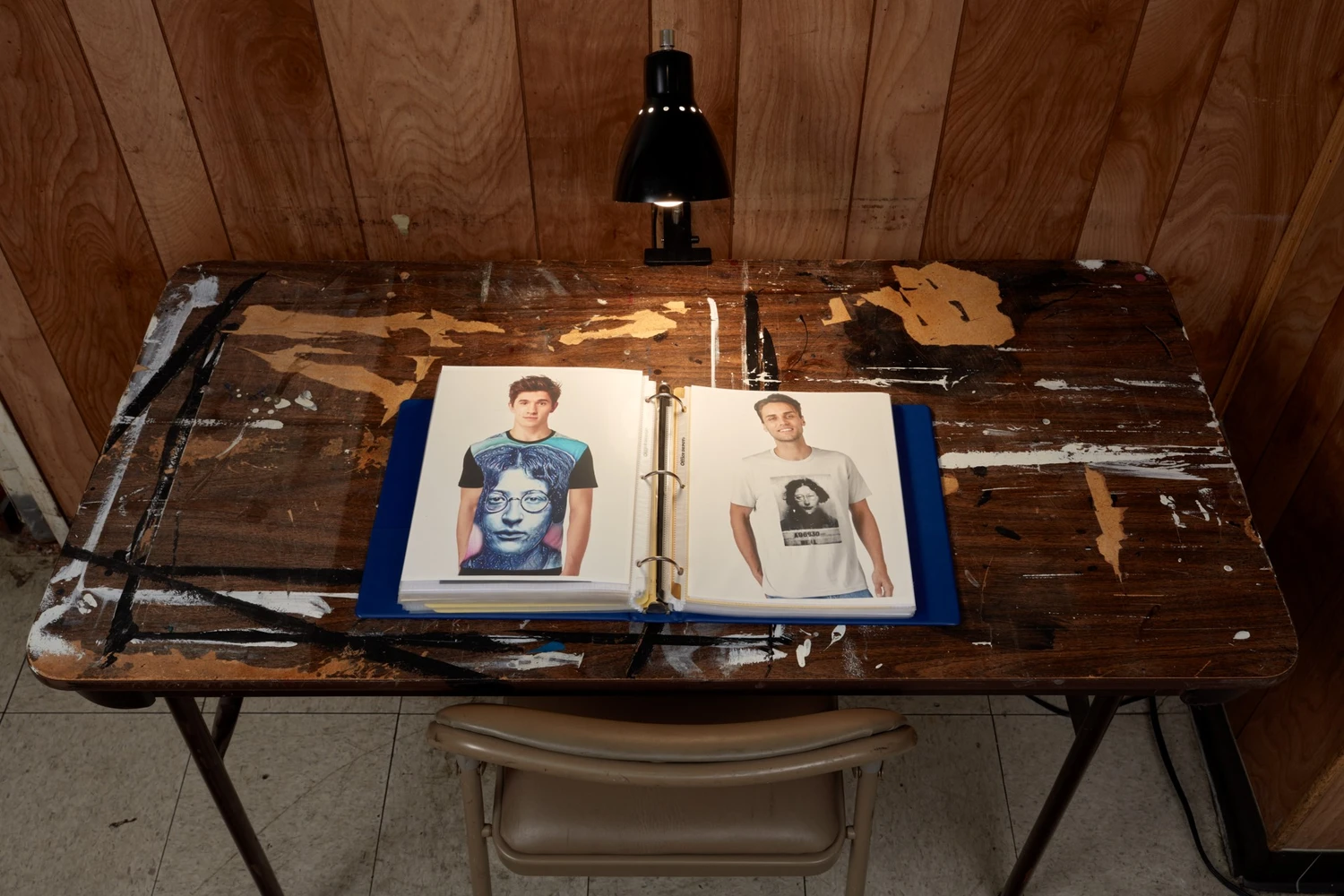

Klahr's examination focuses on an oscillation that structures public consciousness itself. There are stories the public claims it cannot bear, and there are grisly, brutal stories which it consumes with ease. These categories are fundamentally unstable. The same images, the same facts, the same violated bodies move between refusal and appetite depending on framing, context, and the degree to which consumption can be rendered virtuous. The performances of refusal and consumption do not oppose each other; they are complementary techniques that allow the public to absorb what it claims to disavow while preserving what Klahr identifies as "a vaporous sensation of innocence."

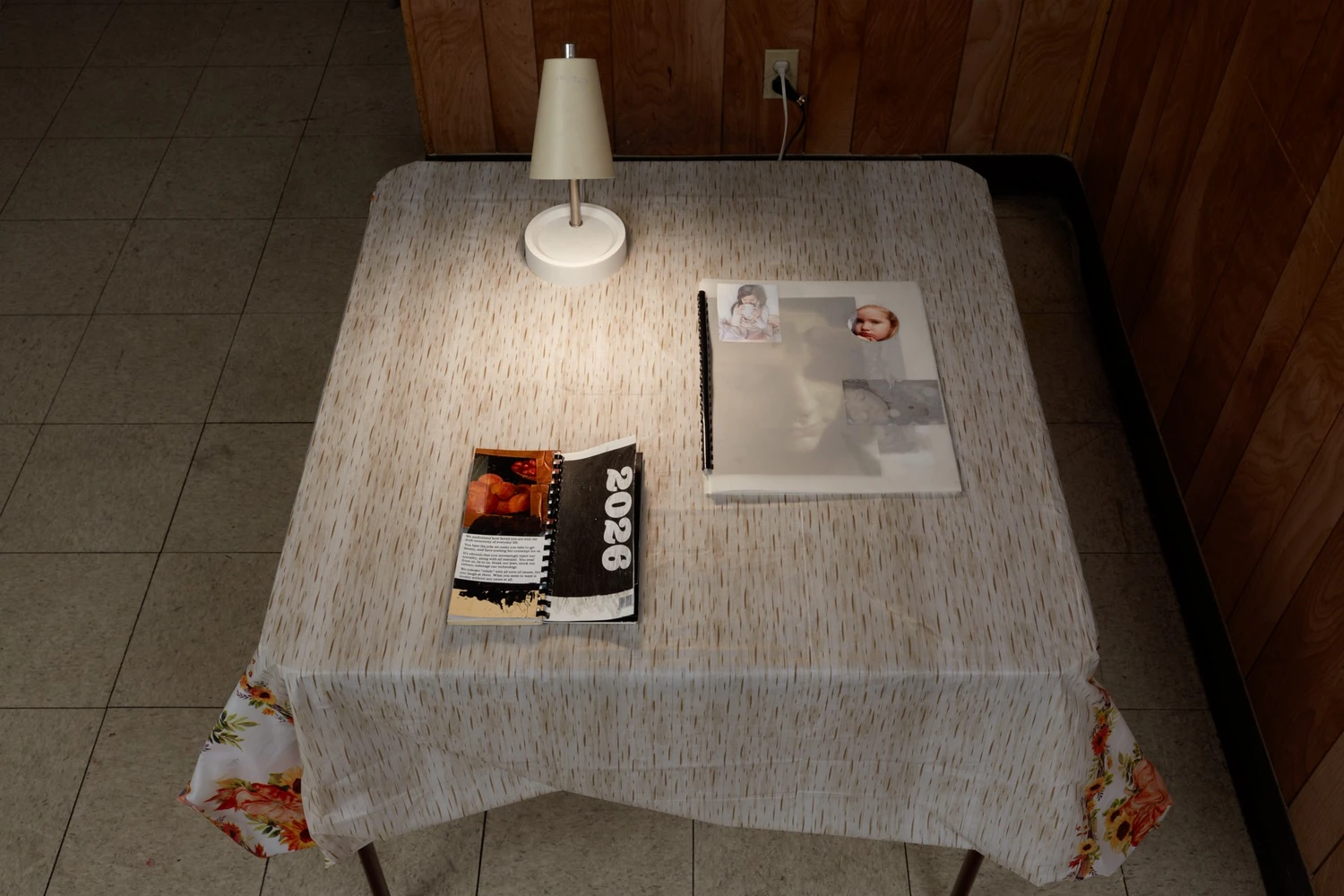

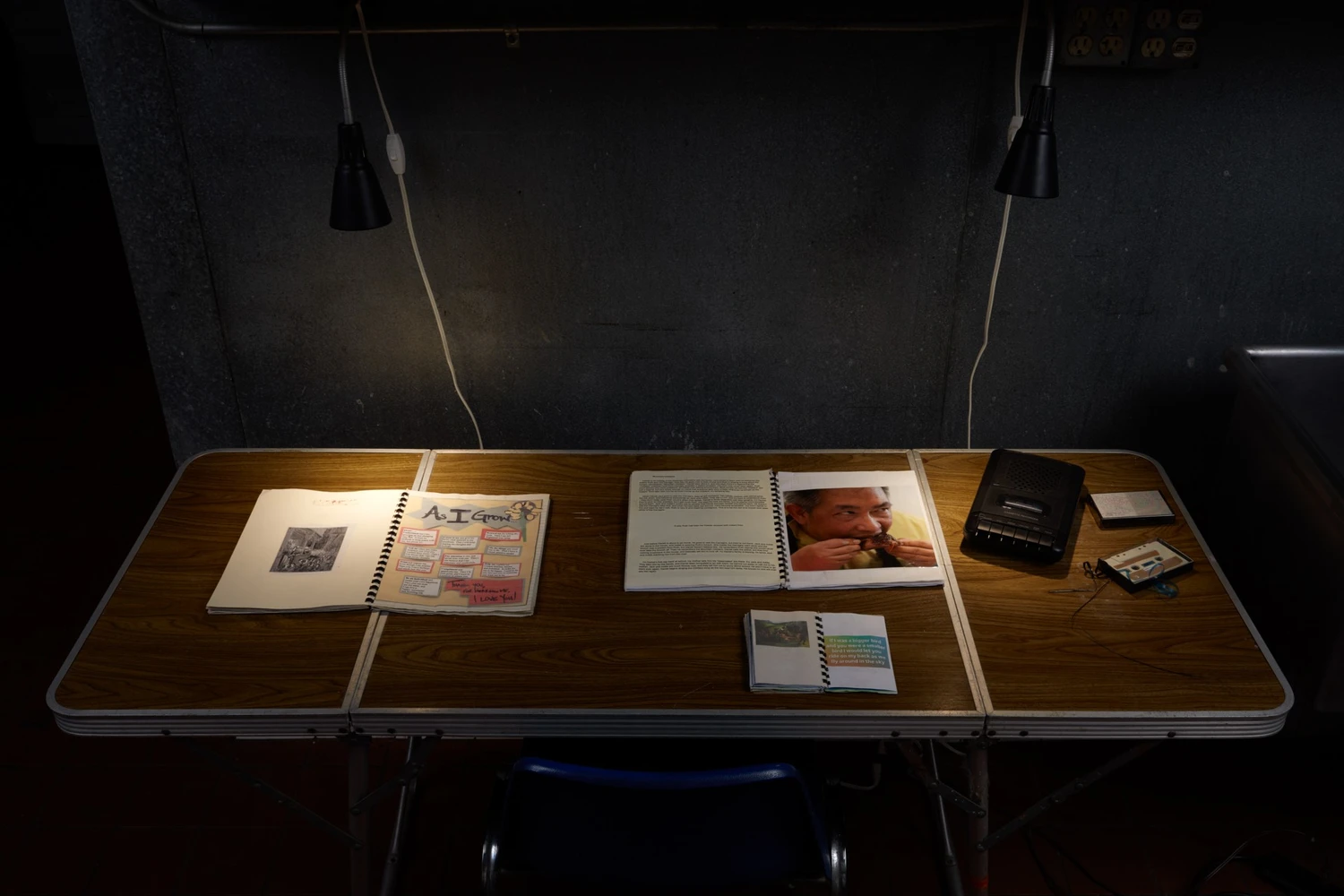

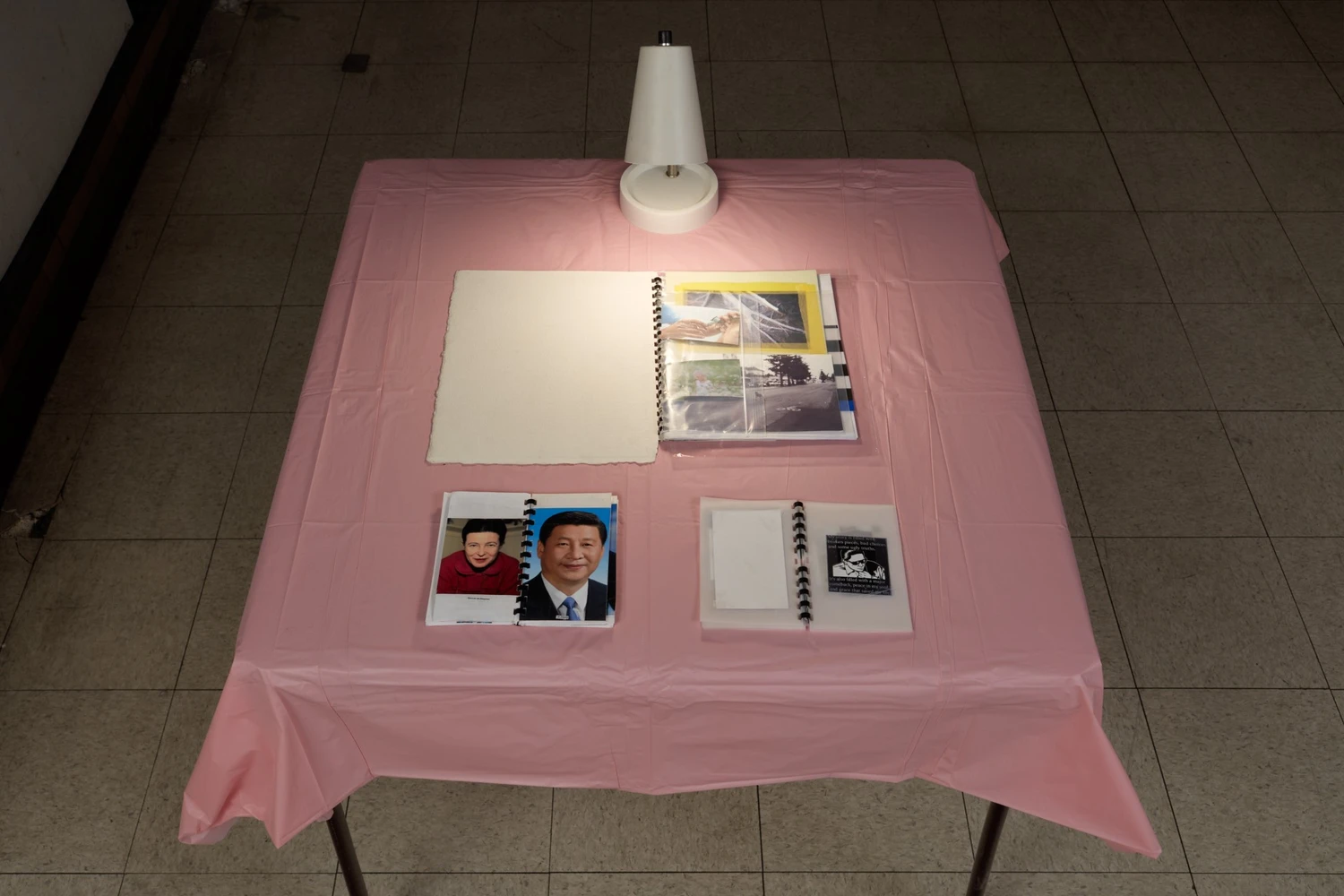

The centerpiece of this analysis is the case of Genie, the feral child whose imprisonment and subsequent exploitation crystallizes the entire logic of public life under scrutiny. Genie spent her first thirteen years in a back bedroom with sealed windows, strapped to a chair by day and confined in a straitjacket-like harness at night. When she emerged in 1970, unable to speak, she became immediately legible to the scientific establishment as an opportunity—a rare chance to study language acquisition, cognition, developmental plasticity.

The narrative that follows is crucial to Klahr's argument. Genie's language abilities were treated as evidence, proof of what could be recovered, what damage might be reversed. But as funding dried up and professional disputes fractured the research team, Genie was moved between foster homes and care facilities. She lost her newfound abilities of speech. The extraction was complete, the usefulness exhausted, and what remained could be safely abandoned. This cycle—exposure, extraction, exhaustion, disappearance—constitutes the true structure of institutional care.

The installation's staging of anonymous figures in animal costumes, their bodies arranged in positions of helplessness or collapse, enacts this logic visually. These are not individuals but subjects within systems, their specificity erased by their reduction to types. The warm brown tones and dramatic shadows create an affective space of profound discomfort—a refusal of the viewer's comfort even as the work asks for contemplation.

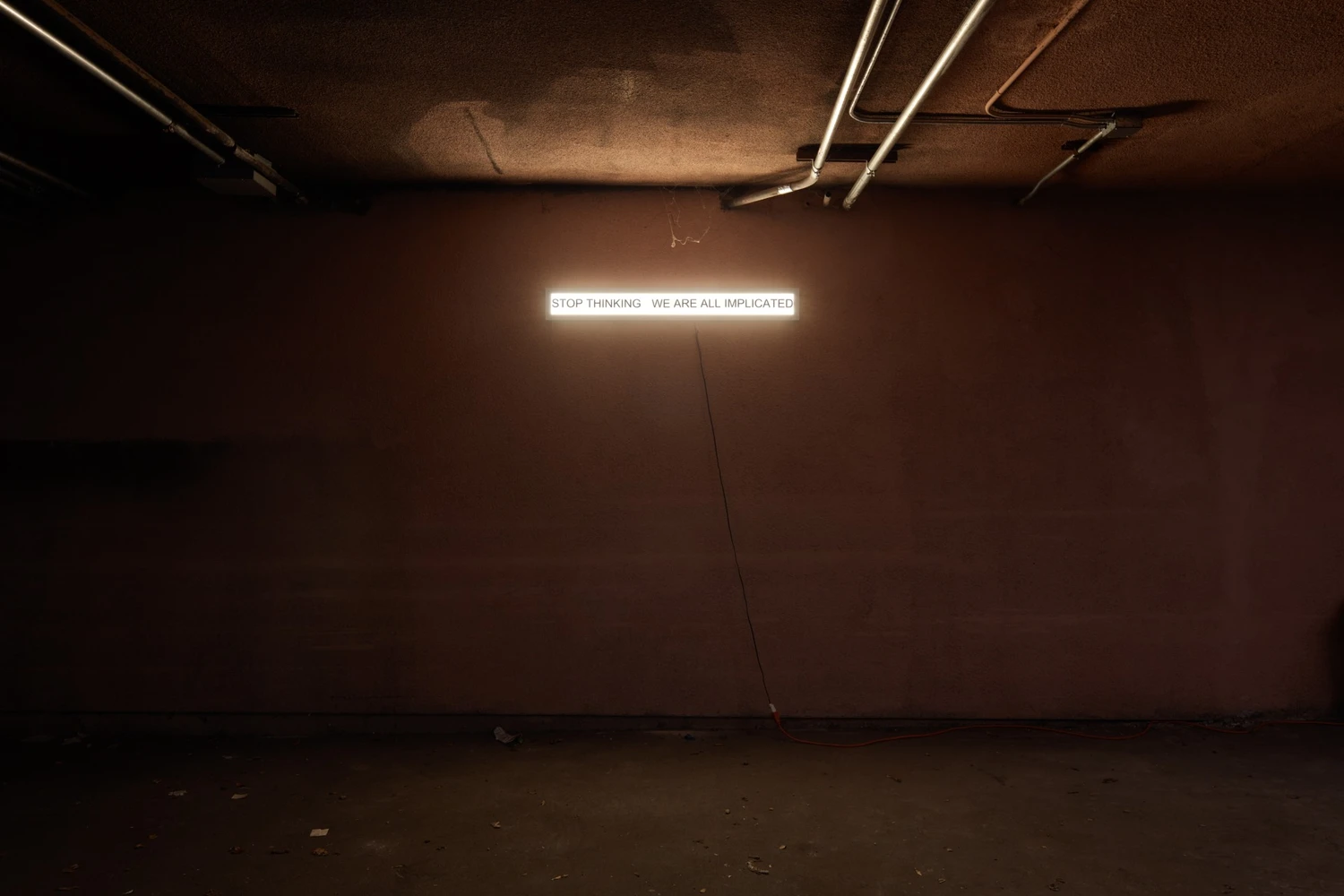

What makes Klahr's work particularly cutting is its refusal of moral alibis. The work does not position the viewer as innocent observer. Rather, it suggests that what occurs within institutions relies on a kind of public subscription—a willingness to believe that harm done in the name of salvation, correction, or scientific progress can be rendered acceptable. Harm becomes an acceptable byproduct, justified by claims that damage must be done now to prevent something worse later. The fictions undergirding public life—that exposure equals empathy, that withdrawal can be morally neutral once usefulness expires—these are not aberrations but the very foundations on which contemporary institutions rest.