At Mendes Wood DM, Precious Okoyomon’s exhibition It’s important to have ur fangs out at the end of the world unfolds like a fever dream whispered by a child in the dark — tender, erotic, and faintly apocalyptic.

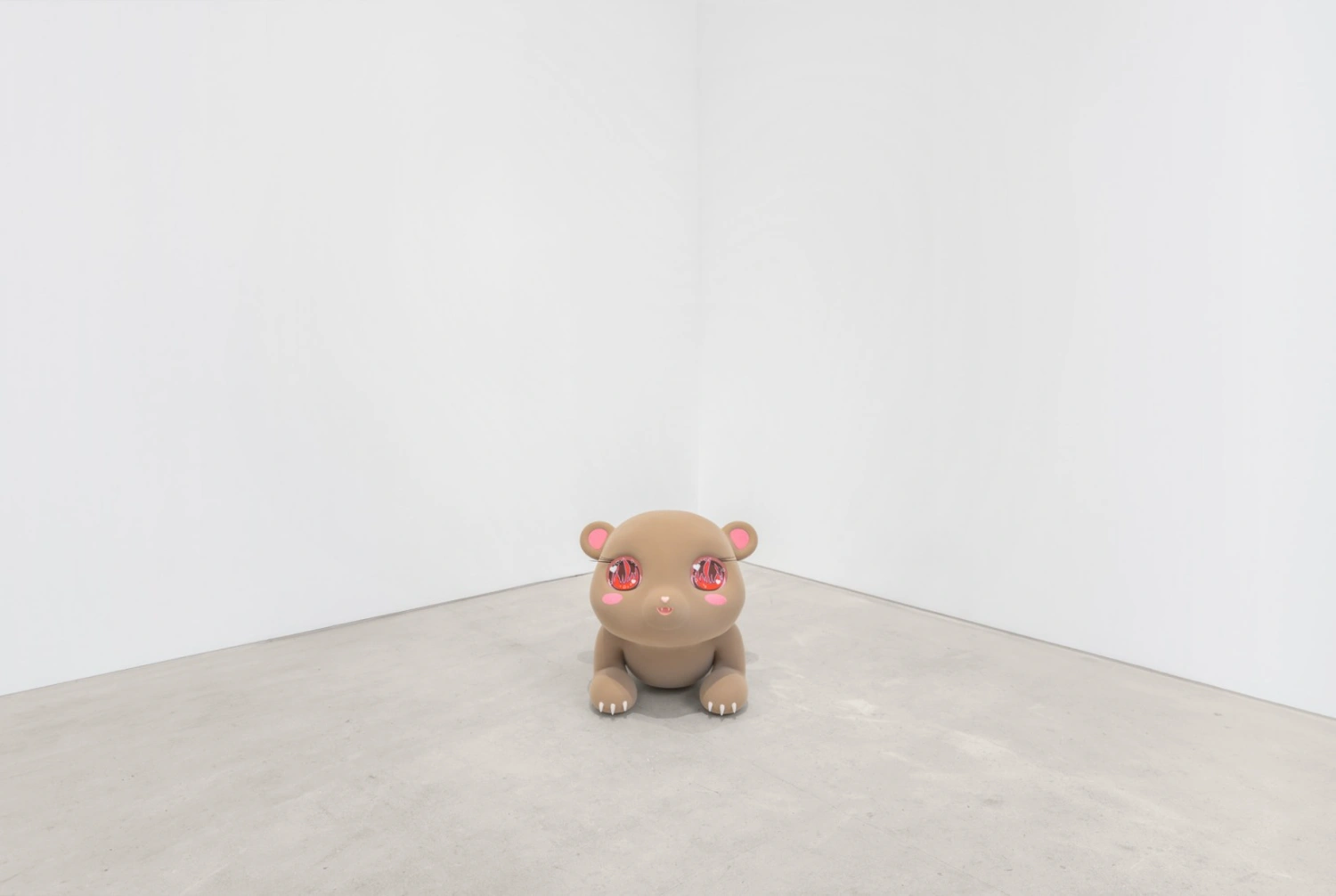

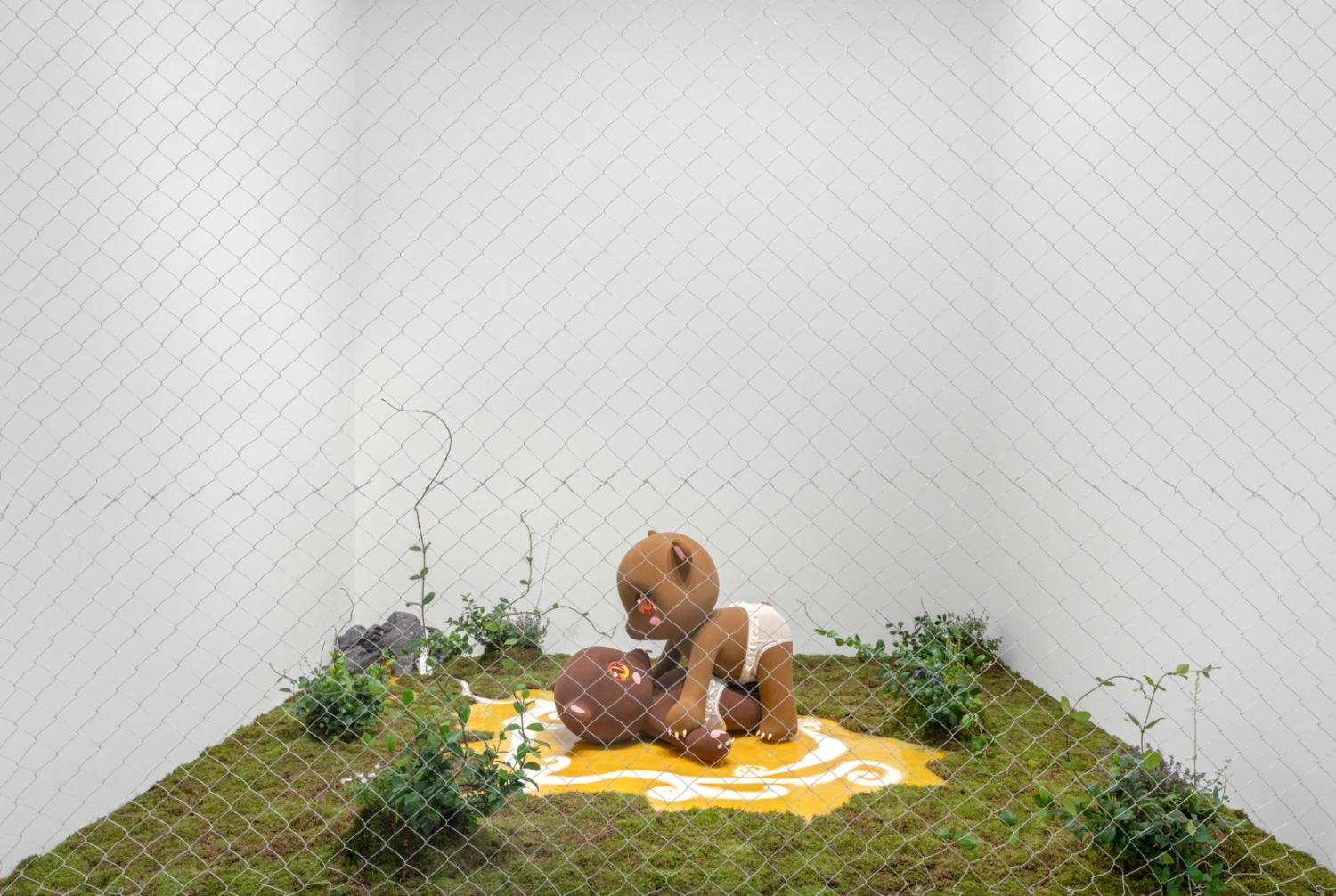

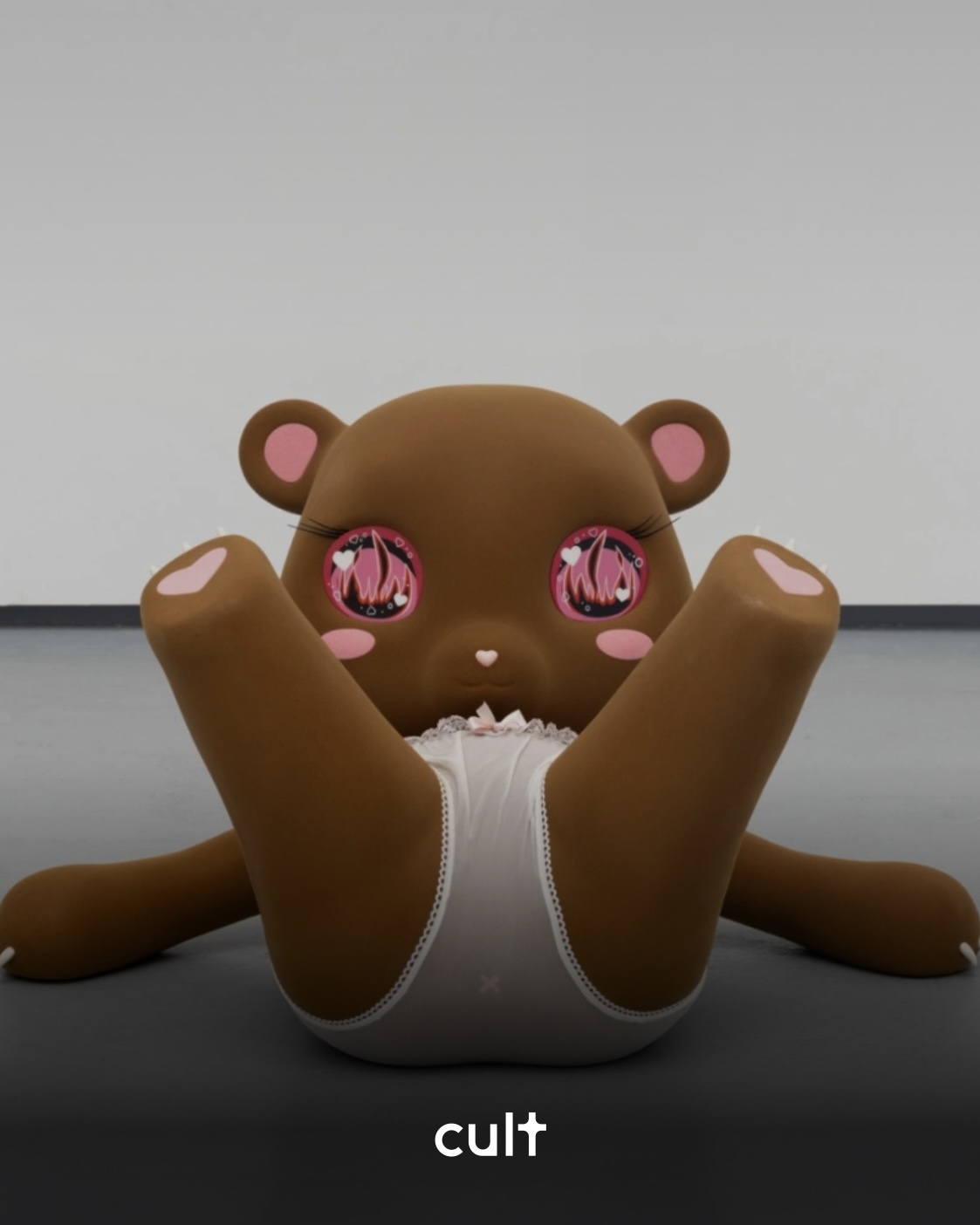

The show gathers drawings, wallpaper, dioramas, and monumental plush sculptures to weave a cosmology where intimacy, ecology, and spiritual collapse coalesce. What appears, at first glance, as unbearably cute — chubby bears in lace underwear, wide-eyed and glowing — quickly reveals itself as an exploration of what it means to exist relationally in a dying world.

If one were to reduce the show to a single sensation, it might be the moment just before touch: the quivering air between two beings who sense each other’s heat. “If one were to reduce matter to its smallest unit,” writes Okoyomon, “it would come down to particles... yet such units never exist in pure isolation.” This is not just physics but ontology. Everything here hums with the understanding that to be is to be in relation — a philosophy that connects the artist’s interest in ecological entanglement with Peter Sloterdijk’s anthropological idea of human “spheres”: fragile, intimate worlds of co-dependence that define subjectivity itself.

The wallpapered space is patterned with floating cartoon eyes — disembodied orbs that blink, drift, and watch. They are particles, souls, spores. Their repetition turns the gallery into a membrane — a porous boundary between inside and outside, self and other. Within this soft delirium sit Okoyomon’s signature bears: eroticized yet innocent, plush yet uncanny. They wear panties like armor, their kawaii eyes swirling with flames. One sprawls in a pose that borders on obscene; another straddles a partner in a tableau equal parts tenderness and perversion.

There’s a violence in their vulnerability, a deliberate confrontation with what the artist calls “the structural violence of sexual shame.” But these bears don’t submit to the gaze; they invert it. Their giant eyes seem to burn back, reflecting desire’s volatility and the instability of innocence itself. They are “transitional objects,” recalling Winnicott’s theory — intermediaries between self and world, fantasy and reality. Like a childhood toy infused with the psychic residue of care, they mark the porous threshold where internal and external worlds meet and mutate.

In Okoyomon’s cosmology, fragility is not weakness but a “radical condition of care and transformation.” This notion — borrowed from artist-theorist Bracha Ettinger’s idea of fragilization — runs through the exhibition like a quiet mantra. To be open to another, to the earth, to pain, is to allow oneself to be undone. The bears’ overexposed, absurdly vulnerable positions embody this ethos. Their “asses praise the sky,” as the text describes — a gesture that is at once devotional, erotic, and ridiculous. It’s through such gestures that Okoyomon disarms the binaries of purity and obscenity, love and violence, child and adult.

Beyond the plush surfaces lies a more ominous undertone. Flames flicker inside eyes and paintings alike; vines creep in dioramas; a faint sense of apocalypse hums through the installation. “From a particle’s point of view,” the artist writes, “any act of creation implicates the end of the world.” Here, the apocalypse is not a singular event but a mode of being — an endless cycle of decay, rebirth, and co-dependence. It’s the recognition that ecosystems, like relationships, only thrive through dissolution.

The exhibition’s fable-like tone — equal parts Genesis and Pleasure Island — reframes collapse as communion. Okoyomon’s world is populated by beings who lick their wounds and each other, who mourn through excess, who metabolize trauma into new forms of tenderness. As with Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes, fragmentation becomes both structure and survival strategy. Through disjointed scenes of carnality and care, the work insists on sacredness “in the chaotic mess of desire,” proposing love not as sentimental redemption but as a method of exorcism.

Okoyomon’s practice — sprawling, poetic, and unflinchingly corporeal — is not interested in transcendence. Instead, it roots itself in the compost of experience, where every particle, every bruise, every bear in its lacy underwear becomes part of an ecosystem of care and undoing. To have one’s “fangs out at the end of the world” is not an act of aggression, but of readiness — to bite, to love, to mourn, to dissolve.

In this shimmering, sticky apocalypse, Okoyomon invites us to imagine relation as salvation. Everything is trembling. Everything is touching. And everything, already, is ending.