Stepping into Esteban Chanez’s The Beasts (Les Bêtes) feels less like entering a gallery than trespassing into the sanctum of a parallel mythology—one sculpted not from inherited doctrines but from fugitive ecologies and misfit imaginings.

What unfurls across the room is not an exhibition but an ecosystem, a cross-species pageant of ceramic beasts and vegetal matter that sidesteps natural history in favor of speculative folklore. These are not animals; they are agents of unlearning.

In his sprawling installation, ceramic dragons curl into moss beds like sacred fauna awaiting communion. Their scaled bodies, glazed in opalescent greens and burnt reds, recall both medieval grotesques and video game avatars. The moss, real and faintly decomposing, stages a ritualistic contradiction: nature as artifice, and artifice as nature. Nothing is fixed. Everything sprouts.

The artist’s references are wide-ranging—ranging from the somber illumination of medieval bestiaries to the ludic spatiality of Zelda and Dungeons & Dragons. But unlike the taxonomies of old—which aimed to classify the unknowable into moral fables—Chanez subverts classification altogether. “Why create bestiaries of animals that do not exist?” he asks, not rhetorically but insistently, as a call to un-map, un-define, and reimagine.

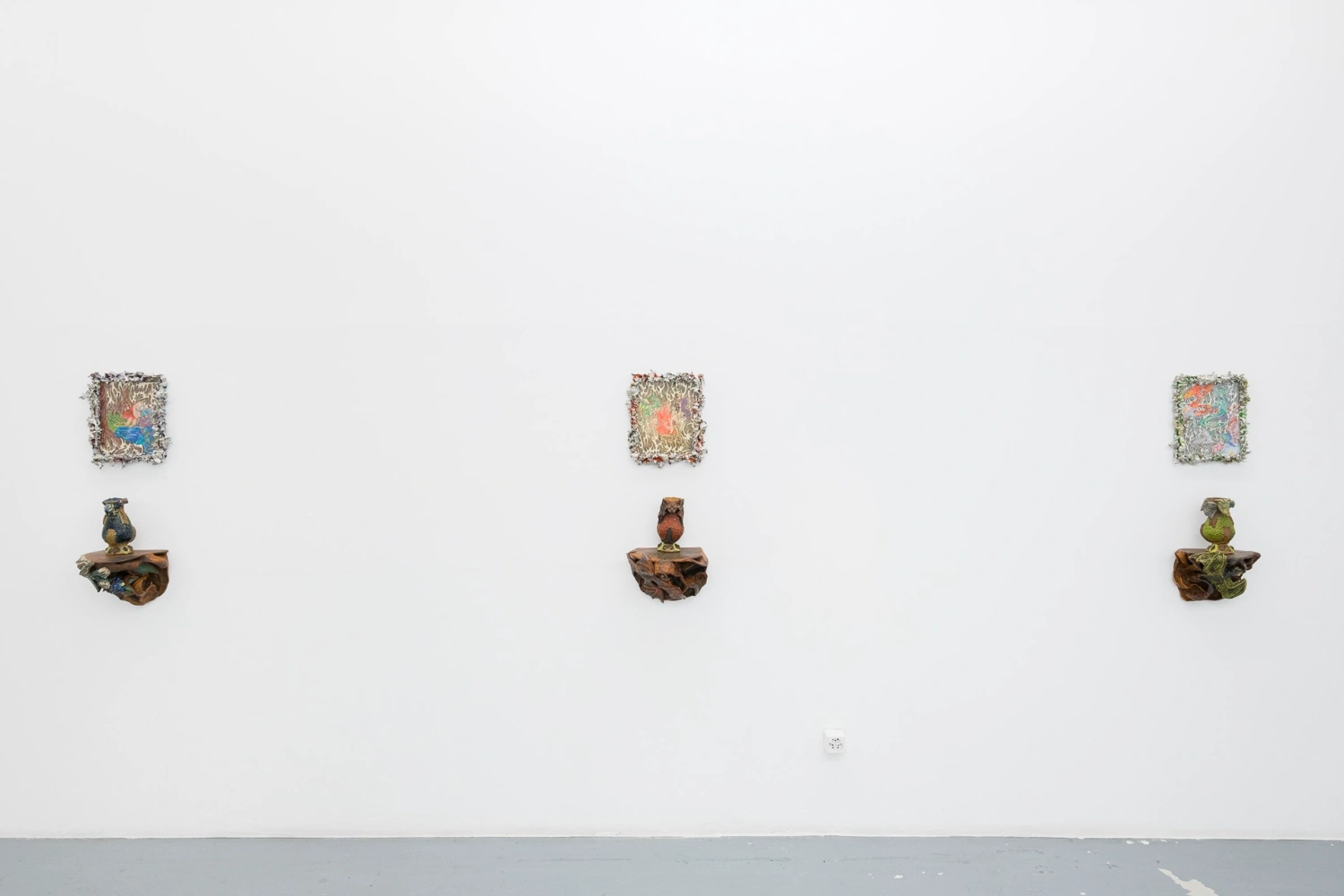

His ceramic sculptures, at once baroque and biomorphic, operate as semi-functional artifacts. A chalice morphs into a serpentine head; a dragon’s open mouth becomes a spout. These are ceremonial objects from a cult that doesn’t exist—altarpieces for a syncretic faith where tenderness replaces theology and mythos resists meaning. Some pieces echo the utilitarian: a Savoyard grolle reappears, but instead of pouring wine, it spills narrative. Its surface is blanketed in living moss, literally rooting the piece in an imagined ecology that gestures to forgotten rituals and animist sensibilities.

Le Grain, Genève, Switzerland

Here, Esteban Chanez positions the animal not as subject, but as sovereign. His beasts are not pets, nor prey, nor parables. They are, to borrow Donna Haraway’s lexicon, companion species—beings that destabilize the borders between human and non-human, subject and object, body and vessel. “His ceramic chimeras become musical instruments that express themselves,” the artist explains, revealing how sound, sculpture, and sensorial experience fuse into a total work of art. These are not sculptures; they are interlocutors.

There’s something uncannily queer about these creatures—genderless and seductive, grotesque yet alluring. They embody a refusal of binaries, a slippage between categories. A dragon suckles an octopus from its breast. A reptilian torso arches ecstatically, caught in a gesture between aggression and dance. Theirs is a world where taxonomies dissolve and bodies become process, not product.

This dissolution is political. “Esteban subverts the codes of hunting, a certain masculinity, hierarchies, and classifications,” the exhibition text states. The grotesque in his work isn’t ornamental; it is insurgent. By centering animals traditionally cast as monstrous—pigs, hyenas, insects—he allies himself with the abject, the vilified, the misclassified. The beasts are not metaphors for human traits. They are not ‘like us’. They are with us, in all their sovereignty and strangeness.

His universe is undeniably performative, not in the theatrical sense but in the durational, relational one. The lighting, the staging, the mossy mounds—each detail is a score for an unplayed ritual. We are not here to look; we are here to witness. One thinks of Björk or Caroline Polachek’s audio-visual dramaturgies—spaces where sound, form, and myth collapse into ecstatic communion. Like them, Chanez creates environments where imagination reigns not as escape but as resistance.

To reimagine animals, in this context, is not simply to anthropomorphize but to decolonize our vision—to see not through the eyes of empire and science but through the feral gaze of fiction, fantasy, and care. His creatures may snarl, but they do not threaten. They invite. They mourn. They seduce.

In a time when ecological collapse and cultural fragmentation threaten even our dreams, Les Bêtes proposes a different kind of futurism—one rooted not in techno-solutionism but in speculative empathy. Chanez does not offer solutions. He offers mythologies. His ceramic cosmology reminds us that belief need not rely on doctrine, and that beasts—real or not—might be our most honest mirrors.