On the second floor of the Centre Pompidou, where Paris’s Bibliothèque Publique d’Information (BPI) once hummed with quiet intensity, Wolfgang Tillmans has orchestrated a striking farewell. The library shelves have vanished, and in their place lies an expansive meditation on time, memory, and the poetics of the ordinary.

The exhibition, titled Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us, spans nearly four decades of the German photographer’s oeuvre, yet defies any conventional chronology. This is classic Tillmans—art that refuses to fit neatly into categories, weaving an intricate dance between intimacy, politics, and radical subtlety.

For Tillmans, now 56, the Pompidou’s sprawling BPI represents a circle completed. His first visit as a teenager from a provincial North Rhine-Westphalian town was transformative, he tells me, recalling the thrill of encountering culture’s boundless possibilities. Decades later, his own work occupies the same space, interweaving personal archives, massive prints, photocopied abstractions, and unguarded glimpses into lives lived at the margins. It’s as though he’s transformed the library itself into a visual diary, intimate yet accessible, meticulous yet unfailingly democratic.

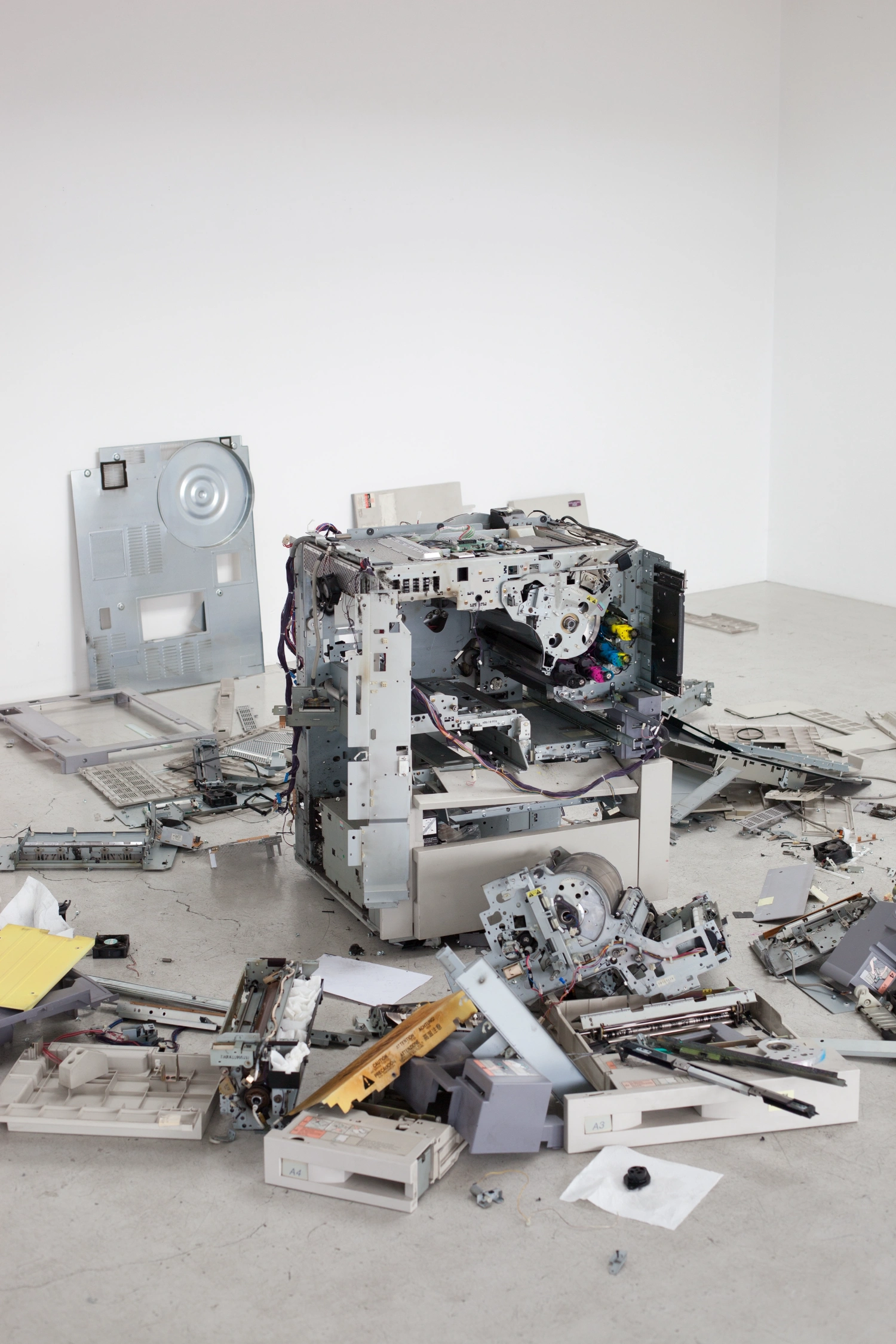

The essence of Tillmans’s project lies in its masterful orchestration of physical and conceptual space. Tables—usually reserved for library patrons—now support photographs, books, magazines, and ephemera. Viewers lean in, picking up texts, photocopying images on-site, their gestures becoming part of the exhibition’s quiet choreography. Nearby, a roomful of photocopiers hums quietly—remnants from the building’s earlier life—inviting interaction and reflection. Tillmans has always relished these ordinary tools, imbuing them with new significance, as he did during his formative years exhibiting blown-up photocopies in Hamburg cafés.

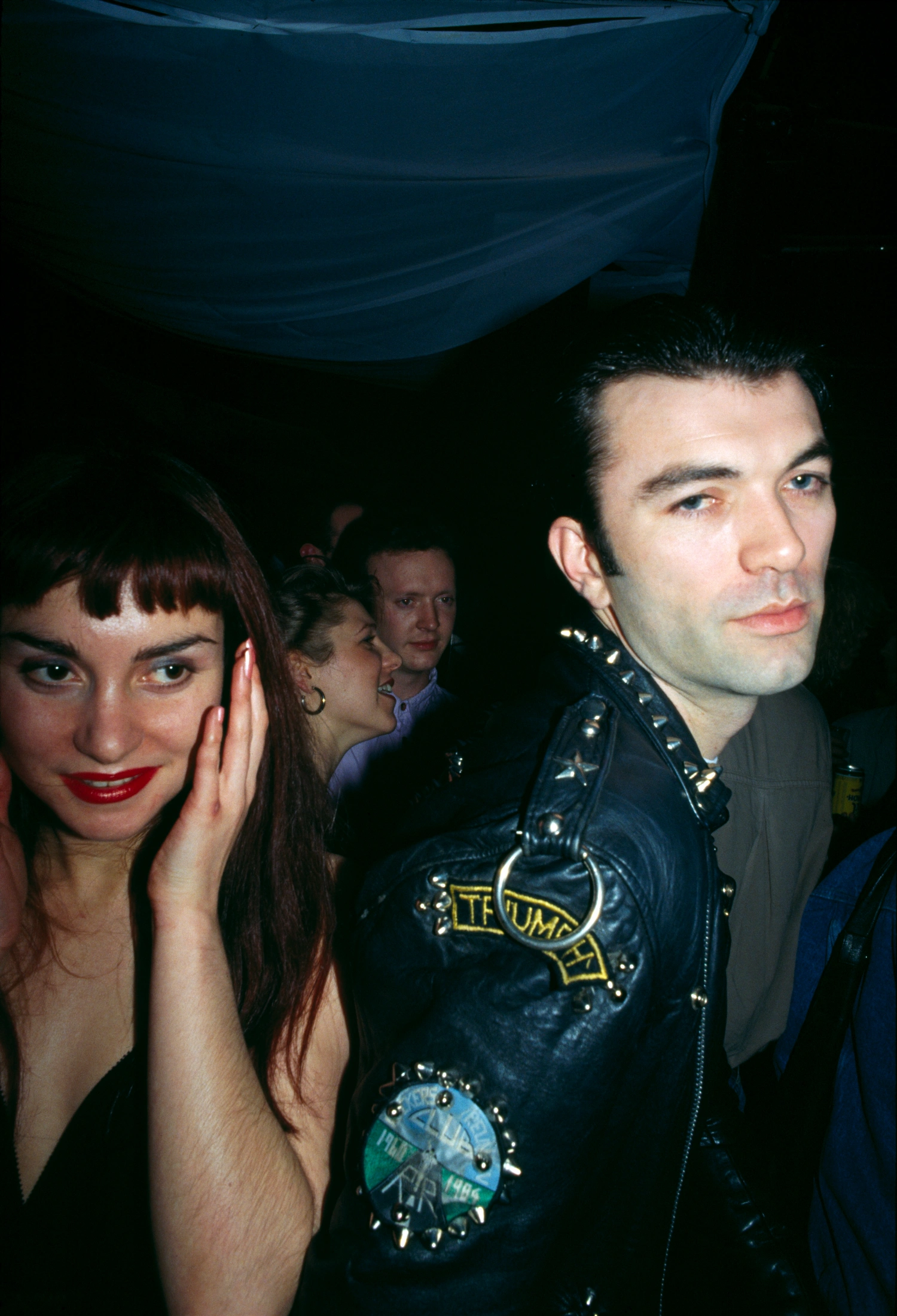

A crucial dimension of the show emerges from its temporal fluidity. Photographs of tropical rainstorms stand beside domestic portraits of Filipina housemates playing cards; queer icons—James Baldwin, Edmund White, Dennis Cooper—fill bookshelves recreated with tender precision. Tillmans arranges these juxtapositions less as statements than as invitations for dialogue. History, identity, politics, and beauty converse freely, challenging and reframing perceptions with each subtle shift in perspective.

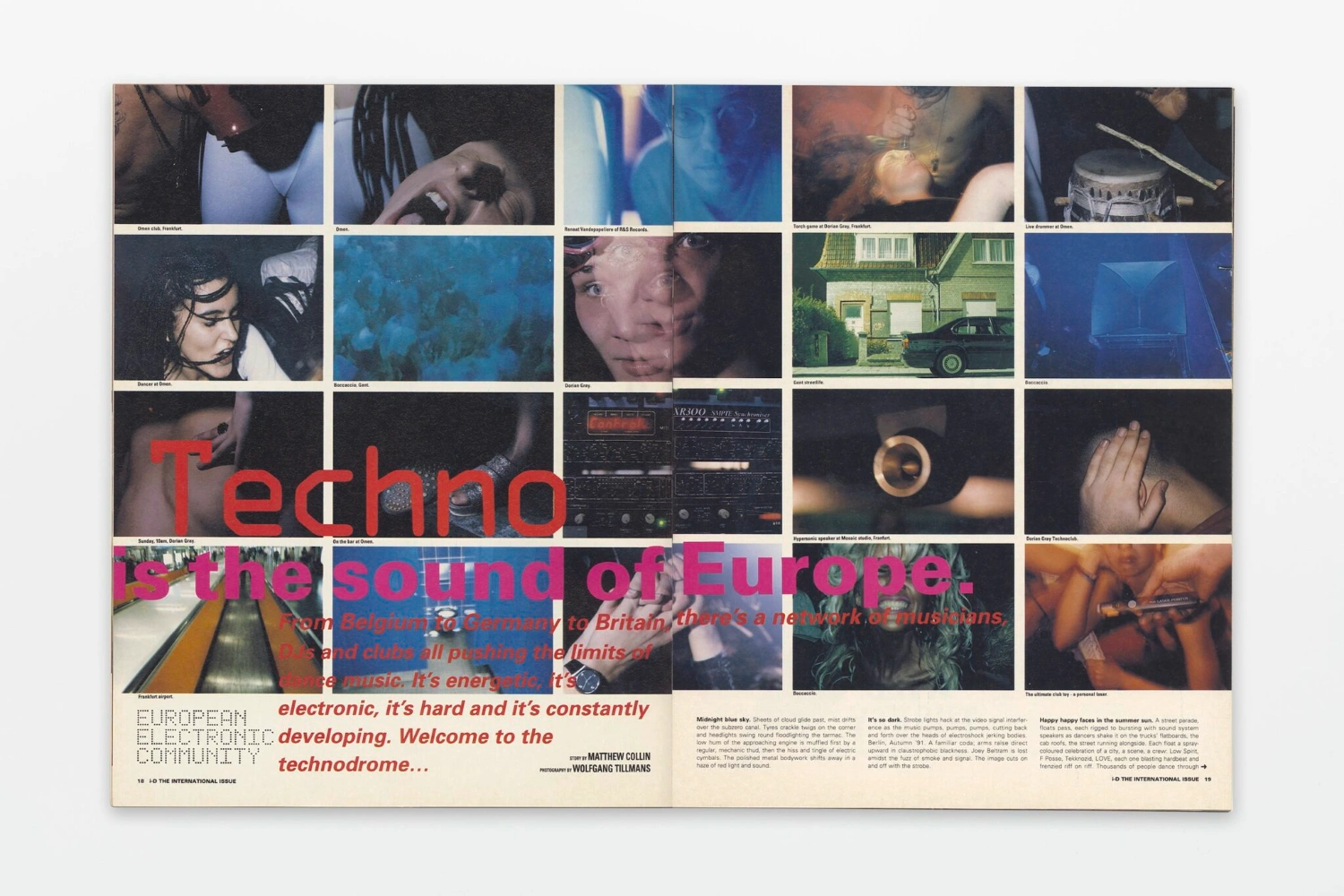

Tillmans’s fascination with archival processes and the life cycle of knowledge resonates profoundly within the former library. Unlike the BPI, known for its brisk culling of materials to remain perpetually current, Tillmans’s approach is conservationist. He exhibits entire copies of his photobooks, meticulously archived for such expansive display. A standout is his seminal work Concorde—all 128 spreads meticulously arrayed—an homage both to physical publishing and the ritual of careful observation.

This devotion to observation echoes throughout the exhibition. Screens portray the BPI during a staged opening on a day when the library was usually closed, capturing readers deeply engrossed in their studies. Sixty screens, scattered throughout study cubicles, project the quiet, collective pursuit of knowledge—a utopia Tillmans respects and gently elevates.

Tillmans admits he was initially daunted by the sheer openness of Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’s iconic building, its second floor originally designed without walls, a testament to radical architectural transparency. Embracing rather than resisting the challenge, Tillmans employs sparse architectural interventions—two towering mirrors reflecting the distinctive zigzagged ceiling pipes, an elevated platform—to subtly reframe the familiar, enabling visitors to experience the building anew.

Yet beneath its apparent subtlety, the exhibition pulses with political urgency. Tillmans, who has never concealed his queerness or his progressive convictions, infuses his installation with quiet yet potent reminders of the fragile freedoms under threat today. Posters from his anti-Brexit and anti-Trump campaigns, once immediate political interventions, now speak as historical documents of resistance and loss, amplifying the exhibition’s resonant title.