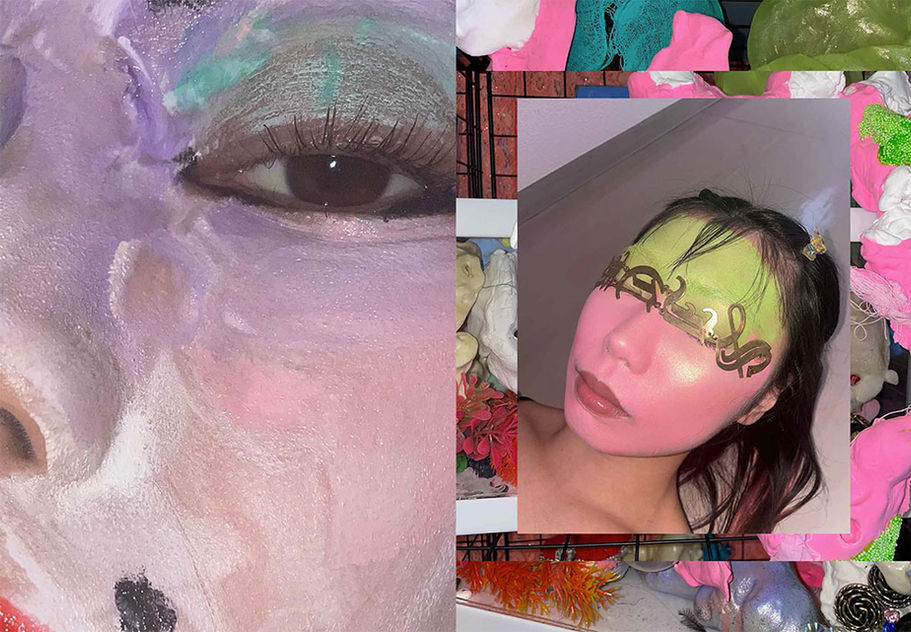

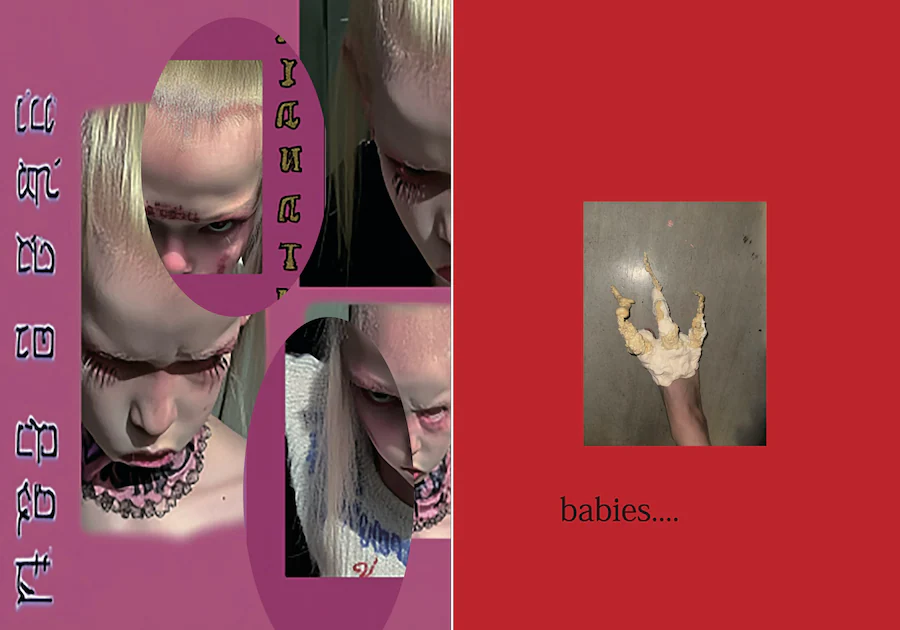

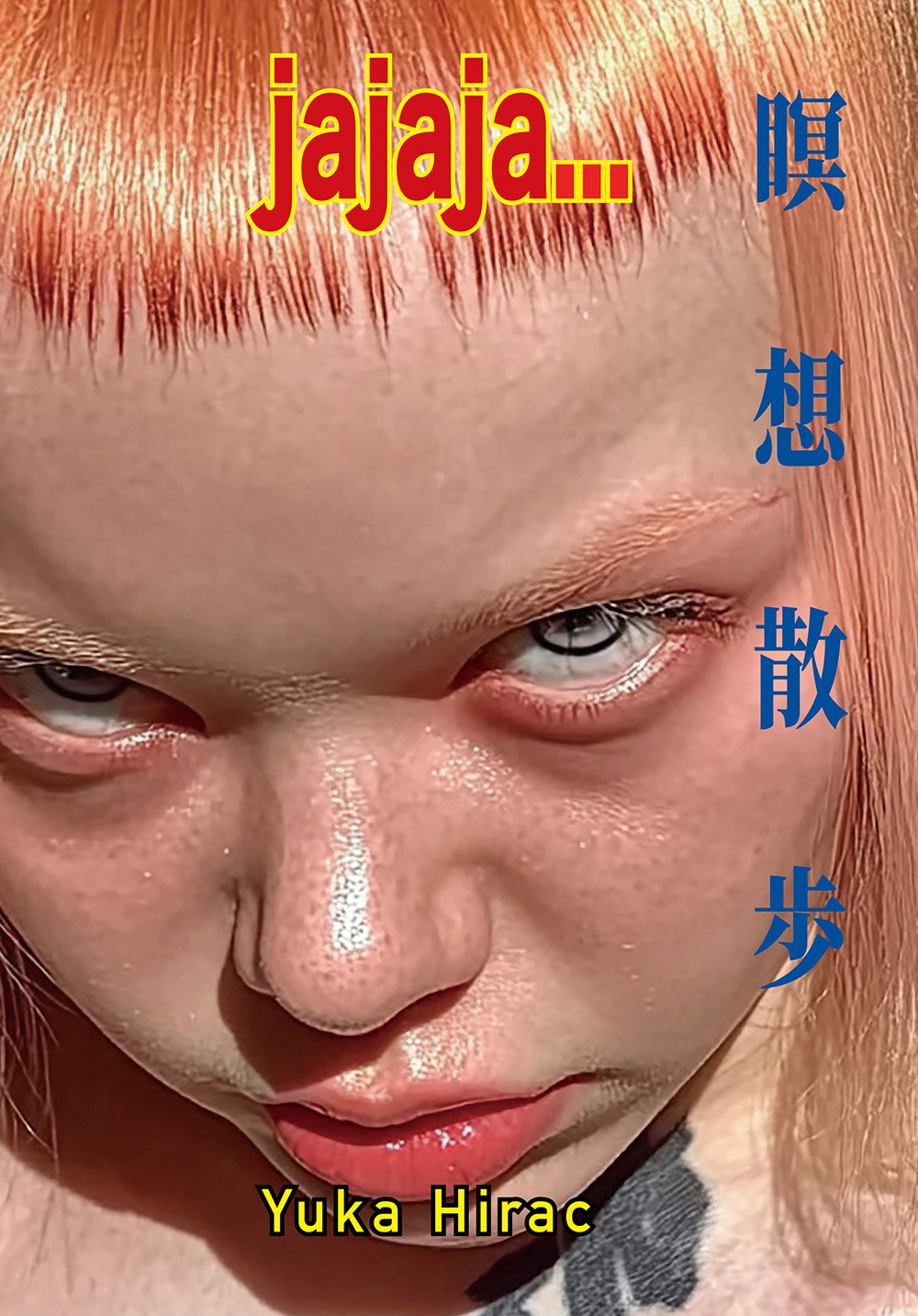

There's something almost violent about the way Yuka Hirac cuts faces apart and reassembles them. "I actually especially like the pages where faces aren't clearly visible," she admits. In her latest zine jajaja…瞑想散歩 (meditation walk), bodies become landscapes, identities become weather patterns, and the self becomes a thing that can be peeled away like old wallpaper. This is what happens when you take the Instagram face—that smooth, poreless expanse of digital perfection—and run it through a paper shredder.

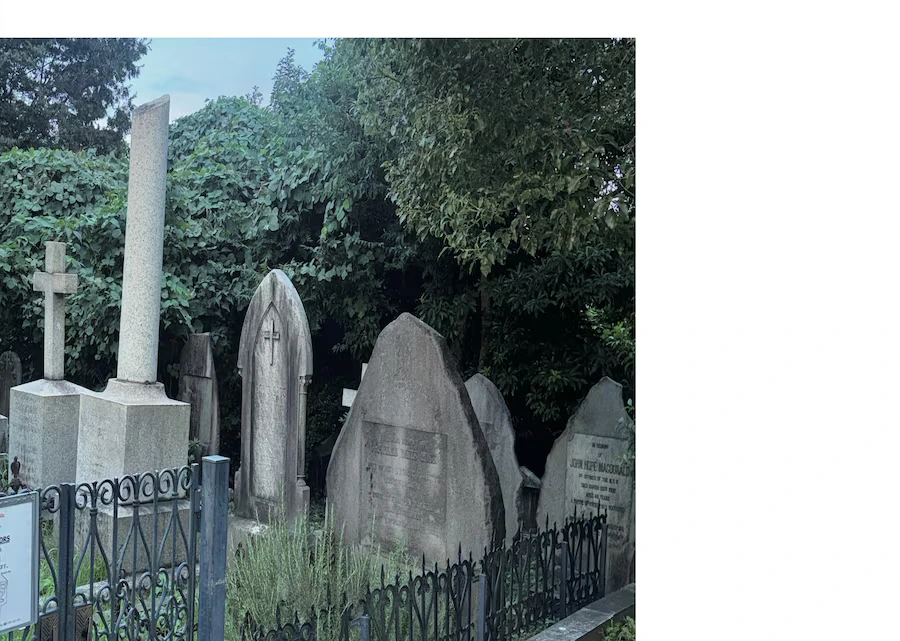

“I find the unknown and ambiguous to be interesting. What happens when we die? Is there an astral projection? An afterlife? It’s still a mysterious world that’s unknown.”

Hirac works in the space between death and dreaming, which might sound pretentious except that she's deadly serious about it. "What do people think when they die?" she asks. The zine centers on the Japanese concept of the revolving lantern—that final movie reel of memories that supposedly plays when you die. But Hirac's version is glitchier, more anxious. "I imagined the life I would look back on when I died," she explains, "and realized I laughed a lot. But when I'm laughing with someone, sometimes it's genuine and sometimes it's fake." Her lantern doesn't just show you your life; it asks whether any of it was real.

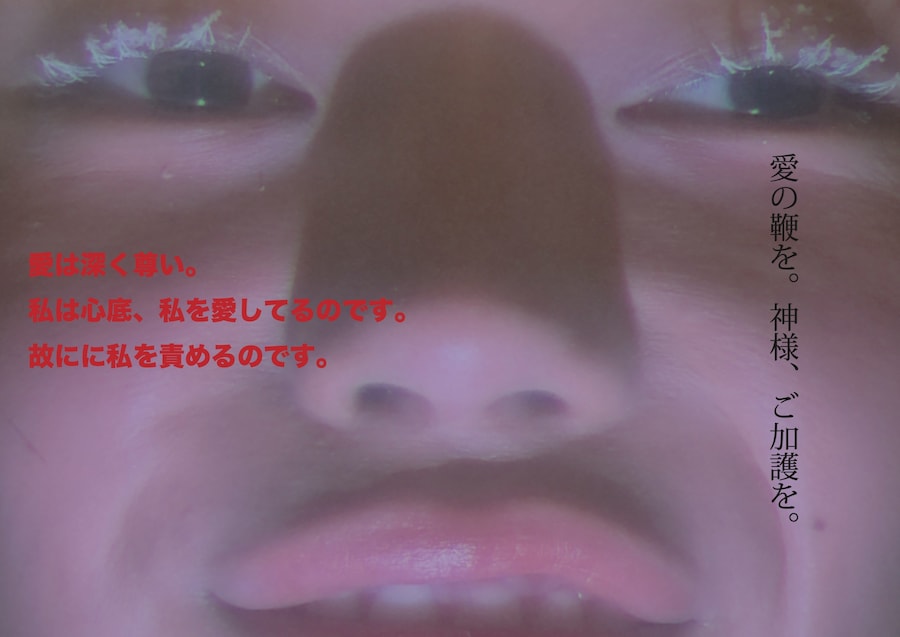

The orange-haired figure that haunts these pages isn't just Hirac's former self—it's all our former selves, the accumulated debris of identity that we can't quite shake. She appears and disappears like a ghost in a broken TV, sometimes laughing, sometimes screaming, always slightly out of focus. This is what nostalgia looks like when it's been digitally corrupted, when memory becomes indistinguishable from glitch.

What makes Hirac's work so unsettling isn't its ugliness but its honesty. "I like giving it an eerie meaning," she says. "Something that makes you feel uncomfortable, that has a strange balance." While everyone else is perfecting their digital masks, she's deliberately breaking hers. Her background as a makeup artist gives her an insider's knowledge of how faces are constructed, how identity is applied like foundation and concealer. But instead of selling fantasy, she's revealing the mechanics behind it.

The DIY aesthetic isn't just about budget constraints—it's about maintaining control over the entire process of meaning-making. In a world where algorithms decide what we see and when we see it, Hirac's hands-on approach becomes almost radical. She sources, assembles, collages, and distributes everything herself, creating a direct line from her subconscious to ours that bypasses the usual gatekeepers.

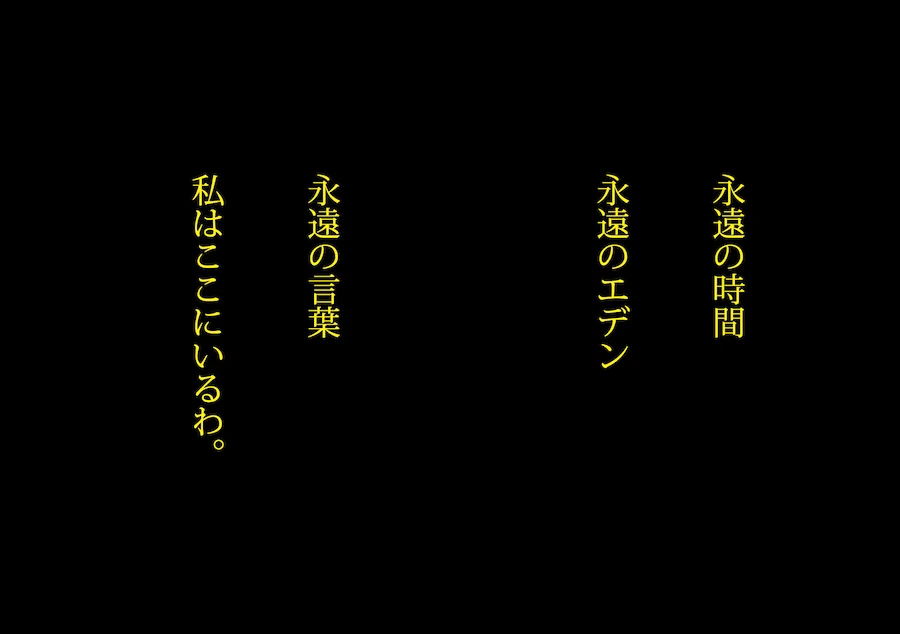

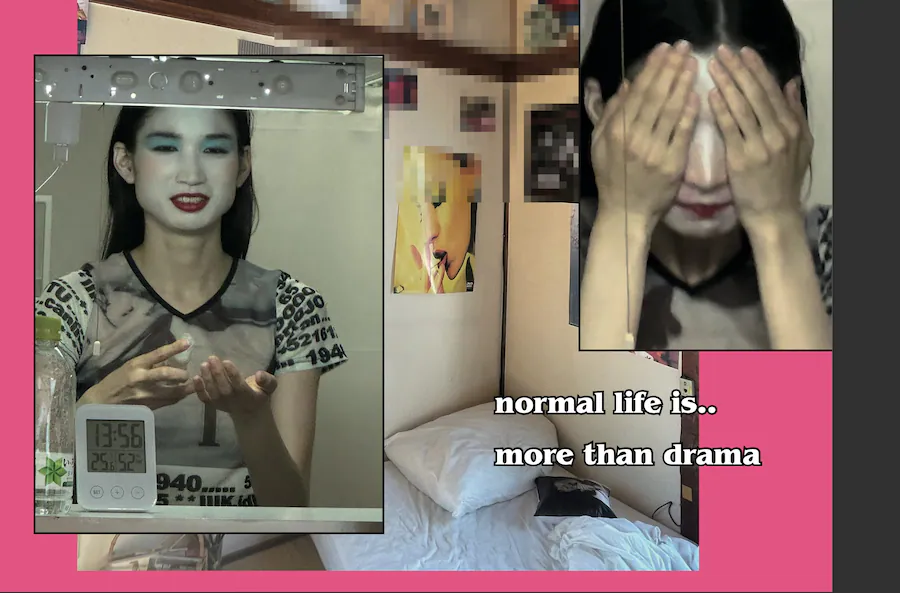

"My fetishes are spirals, loops, overlapping things and the impermanence of all things," she explains. We're all stuck in loops now, scrolling through the same content, having the same conversations, performing the same versions of ourselves. Hirac's spirals become a visual metaphor for this trap, beautiful and nauseating in equal measure.

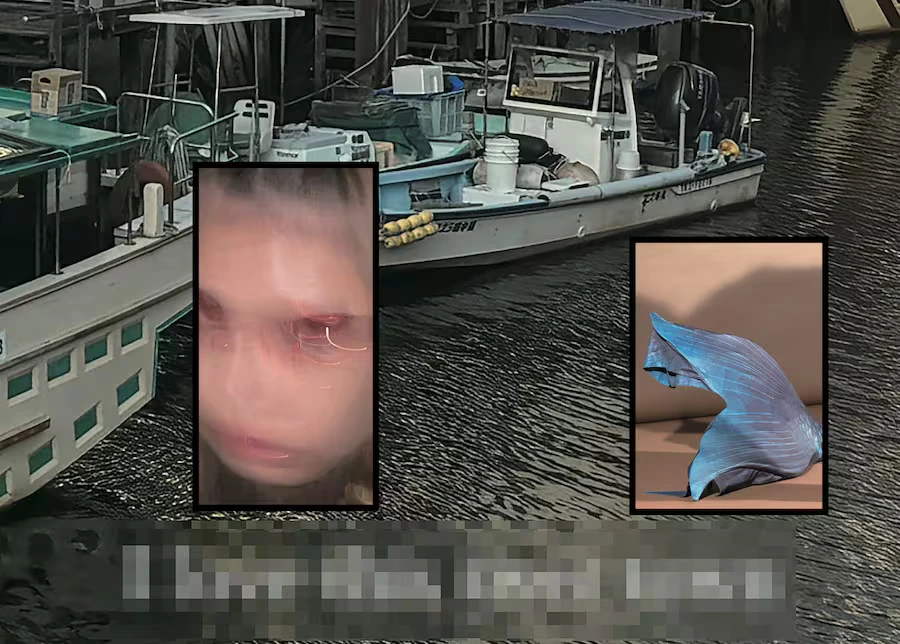

But there's something hopeful in her fantasy of becoming a fish in the next life, specifically a tripod fish that lives in the deep ocean. Fish don't perform their identities; they just exist, moving through space with an unconscious grace that feels almost alien to our hyperconscious moment. In the deep sea, there are no mirrors, no cameras, no audiences—just the pure fact of being alive.

"I imagined the life that I would look back on when I would die, and superimposed it with what I have seen so far, and also what I would like in the next life. Then, I realised that I’ve laughed a lot throughout my life. But when I’m laughing with someone, sometimes it’s genuine and sometimes it’s fake."

This is where Hirac's work gets interesting: she's using the tools of digital distortion to reach toward something predigital, something essential. Her glitches aren't random—they're surgical, designed to cut through the accumulated layers of cultural programming to reveal whatever's underneath. Whether that's the soul or just more programming, she seems less concerned with answering than with asking.

Her zines function as time capsules, documents of what it felt like to be alive and conscious during this particular moment in history. They capture not just the anxiety of digital existence but its strange beauty—the way screen light can look sacred at 3 AM, the way a corrupted image can feel more real than reality.

Hirac's work suggests that authenticity isn't something you find but something you make. It requires breaking things, warping them, making them strange enough that they slip past our defenses and hit us somewhere deeper than recognition. This is art as controlled demolition, clearing space for whatever wants to emerge.