Brendon Burton’s Epitaph unfolds like a requiem for a country that once believed itself infinite. His photographs—abandoned homes sagging into the earth, solitary headstones in desolate plains, a goat staring down the camera outside a weathered farmhouse—are less about decay than about persistence. They record not death, but the long afterlife of what was built and left behind.

Over ten years, Burton roamed the northern Great Plains and the Pacific Northwest, tracing the faint pulse of forgotten structures. In Epitaph, “the quiet desolation and hidden histories that linger in these spaces” emerge as fragments of a larger mythology. The series functions as both an archaeological and metaphysical excavation—one that collapses the distinction between ruin and relic. His houses do not merely crumble; they seem to breathe in slow time, suspended between collapse and endurance.

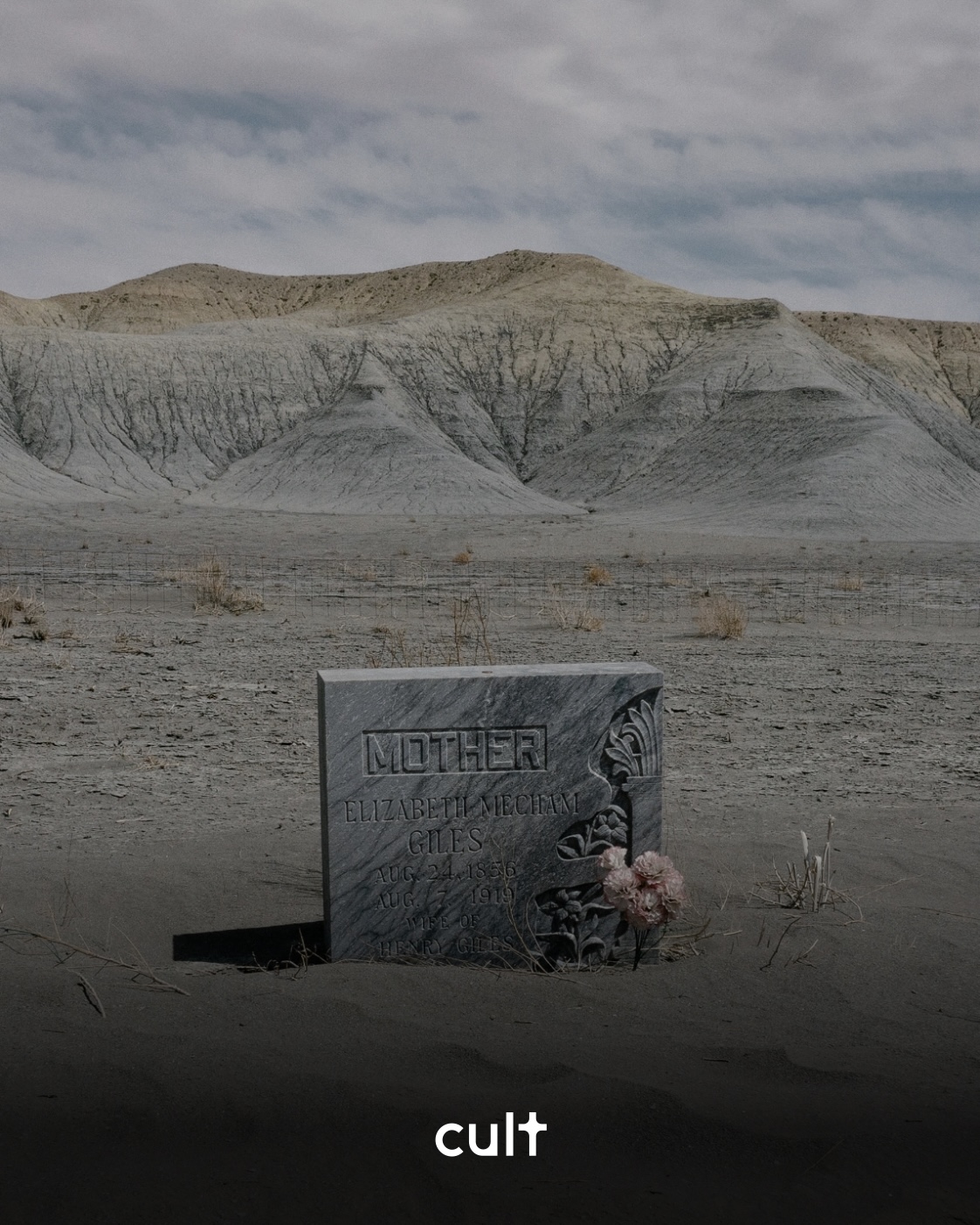

Burton’s images resist nostalgia. Instead, they inhabit a spectral realism, where the human presence exists only as an absence—its trace embedded in wood grain, rust, and dust. The landscapes feel almost sentient, as though the land itself has begun to remember. The photograph of a tombstone inscribed “EPITAPH,” framed by an endless horizon of grey sagebrush, becomes a mirror held up to the American psyche: a culture haunted by its own expansion, now confronted with the erosion of its frontier dreams.

The work’s quiet tension lies in its duality. On one hand, there is a deep tenderness—a sense of reverence for the “unseen histories and buried past lives.” On the other, a distinctly post-human perspective emerges, where nature and ruin intermingle without sentimentality. The overgrown farmhouses and skeletal trees evoke the sublime, but not in the Romantic sense; this is a contemporary sublime of entropy, where beauty arises from decomposition.

Epitaph is also about the photographic act itself—about looking at what remains after everything else has gone. The absence of people is not emptiness, but invitation. As viewers, we are implicated: explorers, trespassers, mourners. The derelict spaces invite projection, forcing us to confront our own impermanence. Burton’s America is less a place than a condition—a liminal territory where memory, architecture, and decay converge.

Epitaph doesn’t so much document abandonment as it performs it. Each image is a meditation on what it means for time to keep moving when no one is left to witness it. “Reality frays,” Burton writes, “and the past lingers, like a fading memory.” In that lingering, a strange beauty takes root—quiet, resilient, and uncomfortably familiar.