In Seoul’s Art Sonje Center, the floor is no longer solid ground. It heaves with soil, moss, rust, and memory. A shattered biome pushes through the white cube’s sterility like a post-industrial resurrection. Adrián Villar Rojas’ first solo exhibition in Korea, The Language of the Enemy, doesn’t just occupy space—it devours, mutates, and destabilizes it.

The museum, once a locus of preservation, now becomes a sentient terrain—entropic and indifferent, halfway between archaeological dig and sci-fi detritus field.

This is Villar Rojas in his most expansive form. Known for creating worlds rather than merely sculptures, the Argentine artist builds on his ongoing cosmology The End of Imagination (2022–), previously shown at Fondation Beyeler and the Helsinki Biennial. But here in Seoul, he doesn’t simply show the work—he lets it colonize. “I model worlds,” he states, “and the worlds model ‘sculptures’ for me.” The show stretches across all four floors, claiming restrooms, stairwells, corridors. The institution becomes carcass, the gallery walls flayed back to concrete and cable. Exit signs glow dimly, not as directives but as ambient apparitions. This isn’t exhibition—it’s exorcism.

Villar Rojas' signature digital-to-physical process hinges on the Time Engine, a speculative software framework powered by AI and video game engines. From this simulation tool, the artist “downloads” hybrid lifeforms—neither sculpture nor character, but algorithmically-evolved relics of alternate timelines. The figures that populate The Language of the Enemy seem caught mid-evolution: biomechanoid torsos kneeling in sand, android limbs clutching washing machines, cable-gutted carcasses sprawled under vine-choked ceilings. Each form is precarious, less designed than unearthed. The impulse is paleontological, but the fossils come from futures we haven’t yet lived.

The installation’s ecosystem is not metaphorical. Villar Rojas and his long-standing crew of collaborators transformed Art Sonje into a literal soil-based habitat. Earth from the outside world was brought in. Temperature and humidity systems were deactivated. Boundaries between the institution and the wild were not blurred—they were collapsed. Visitors don’t simply witness the art, they traverse its ruins. The gallery is no longer neutral—it sweats, breathes, sheds.

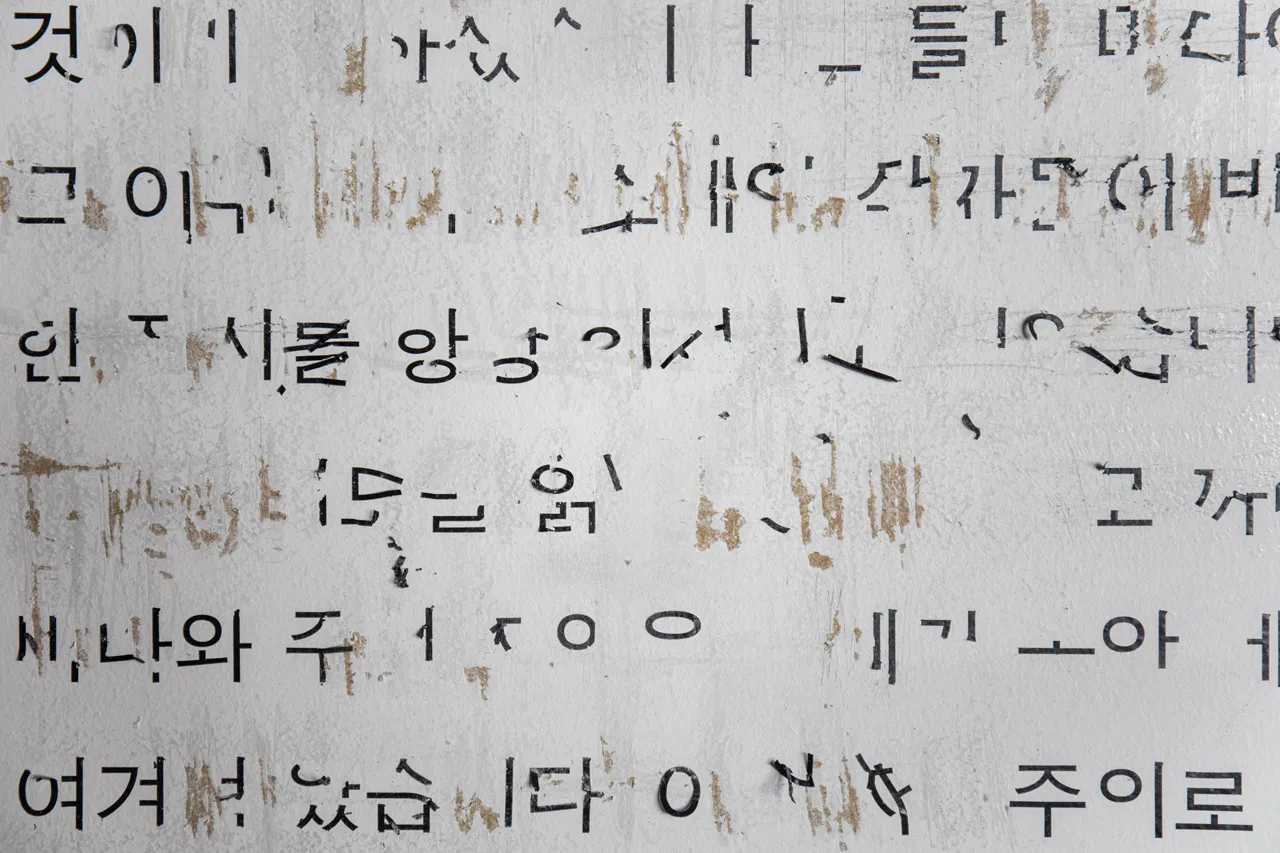

Central to this are Villar Rojas’ notions of inheritance and extinction, entangled in the show’s title. “When I speak of The Language of the Enemy,” he says, “I’m pointing toward a deep prehistory of meaning-making.” Here, ‘enemy’ is not a political other, but an evolutionary one. The enemy is the Neanderthal we coexisted with, the AI we are currently nurturing. In both cases, knowledge is transferred, but also effaced. “In doing so,” he warns, “we may be preparing for our own disappearance.”

The sculptures feel like emissaries of this transition: machines that no longer perform tasks, tools decoupled from use, fragments haunted by extinct purposes. The washing machine—nestled in the center of a creature erupting in mechanical limbs—reads less as appliance than altar. Watermelons dot the terrain like absurd offerings. Industrial waste dangles from vines in suspended animation. In one moment, the future appears fungal and feral; in the next, brutalist and synthetic. Yet it never resolves—it only accumulates.

There is a distinctly post-human temporality at play. Villar Rojas’ works operate on geological and algorithmic time, not linear human chronologies. The exhibition is not “about” the climate crisis, nor AI, nor the Anthropocene in any didactic sense. Rather, it internalizes them. It operates from within the crumbling scaffolds of those narratives, speaking in tongues we’re still learning to decipher.

In that sense, The Language of the Enemy does not simply speculate on the future—it stages its archaeology. It gestures not at what’s to come, but what will be unearthed after. The sculptures are not monuments; they are afterimages. The audience becomes intruder, archaeologist, and ancestor all at once.

This confrontation with the unknown—synthetic or ecological—isn’t framed as horror or awe, but as intimacy. These forms, however alien, speak to us. Perhaps not in words, but in debris, gesture, and glitch. They’re not here to warn or redeem. They are here because we are already gone.