Walking into One Of Us Is Real and It's Not You feels less like entering an art exhibition and more like stepping into a half-decayed, half-rendered dream pulled from the collective unconscious of a generation raised on Tamagotchi, crypto dreams, and digital burnout.

In their first collaborative exhibition, Supermetal Bosch and Evil Biscuit—two artists forged in the furnace of the Avant NFT underground—transform Galerie Yeche Lange into a fractured playroom where synthetic fantasy and algorithmic obliteration battle for psychic real estate.

At the heart of this show lies a question that is more existential than rhetorical: What does it mean for an image to be “real” in an age where reality itself feels increasingly simulated? The answer, if there is one, comes not in neat theory but in form: obelisks etched with non-languages, ceramic figures bearing the semiotics of extinct brands, and pixel-smashed portraits that feel like they’ve been cryogenically frozen mid-Tumblr scroll.

Orgonite mons board, 2025white porcelain, black porcelain, pewter, resin,

aluminum, shungite, iron powder, mica powder,

amethyst, ghost quartz, quartz powder18 x 18 inches

Bosch’s Super Metal Mons! chess-like game boards are perhaps the clearest encapsulation of his artistic philosophy—a literal play space where cultural memory, collectible fetishism, and AI hallucination become gamified. His “Mons”—adorably deranged ceramic figures with ocular voids and squashed proportions—evoke a parallel dimension where Pokémon evolved under the influence of GANs, Adderall, and recession-core fashion. According to Bosch’s own archive-heavy process, these figures are “born of the material of the past and set into the future.” The result is uncanny: figures that look familiar yet mutated, like avatars corrupted by too many cycles of remix.

Bosch’s earlier digital projects, like Little Swag World, were already articulating the weird overlap of underground fashion and financial speculation—here, those tendencies crystallize in clay and concrete. The installations push his speculative economy fantasies into tangible, scuffed matter. In this context, the tired beige leather sofas and giant Mons heads become more than props; they are relics of millennial domesticity caught in a surrealist war zone.

If Bosch builds worlds, Evil Biscuit burns them down.

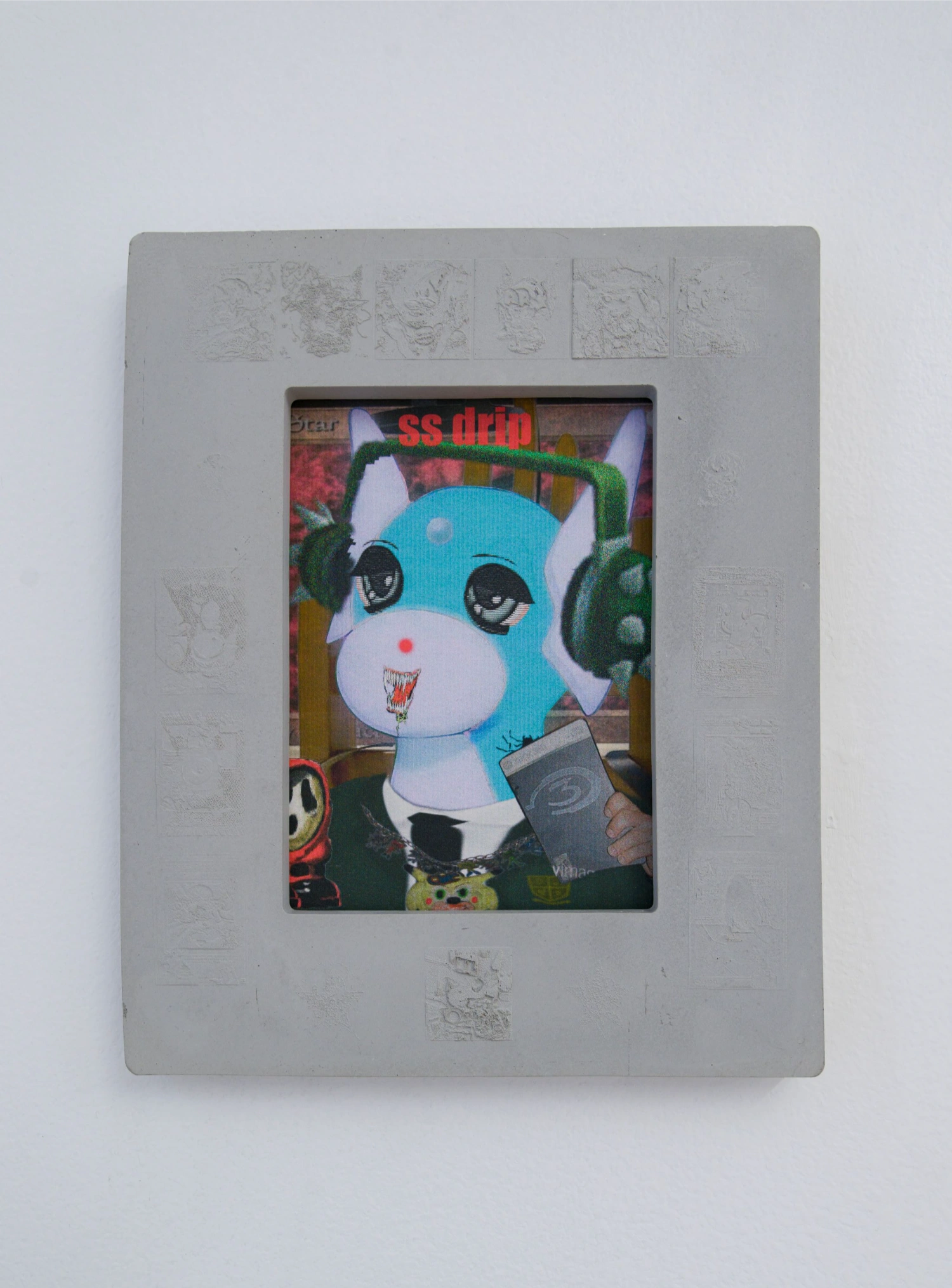

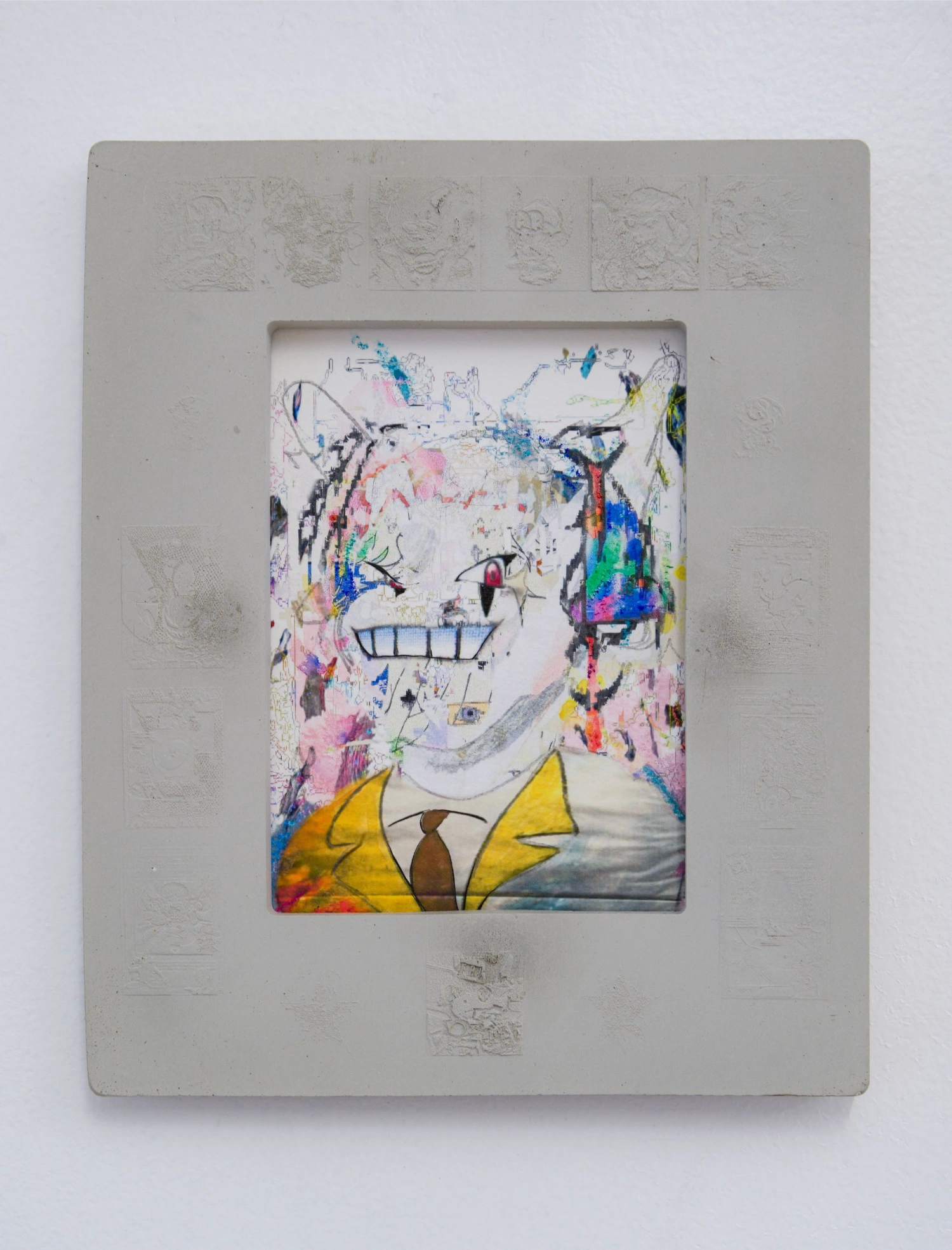

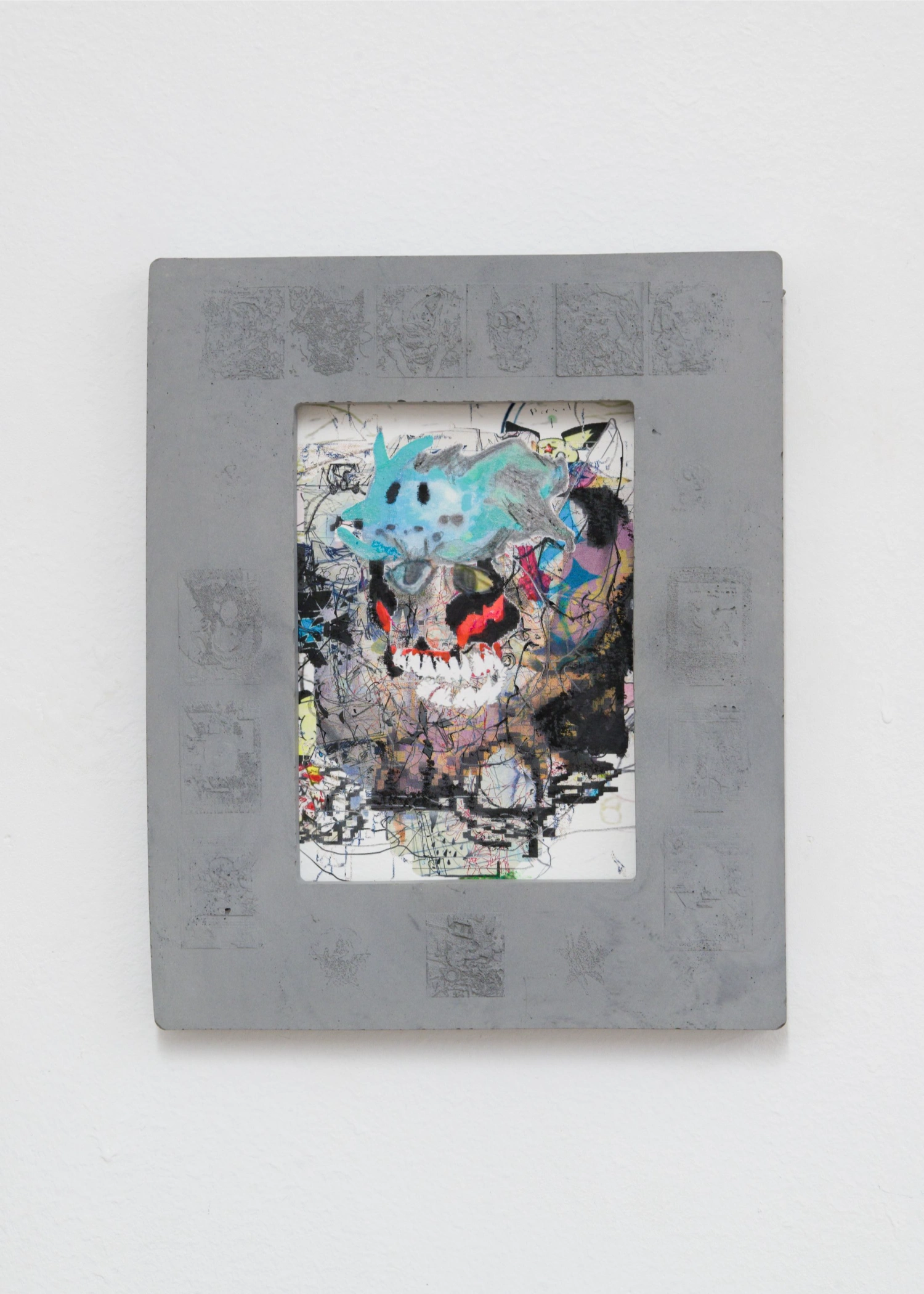

His Drifella works—particularly the large triptych and metal-cast card series—are marked by a visual violence that resists legibility. Obscured faces, glitch-choked palettes, and abrasive layering render the notion of the “profile pic” (or PFP) into an unrecognizable specter. Biscuit’s images are what happens when the machine breaks down mid-scroll: “abstract, gestural, and painterly images that destruct the PFP genre’s initial impulse towards figuration and faciality.”

watercolor paper, hot glue, sla resin frame29 x 31 inches

The frames themselves—concrete, brutalist, and carved with glyphs—act as tombs for dead images. Biscuit doesn’t just kill the idol of the face; he mummifies it. The effect is necro-digital: screenshots turned sarcophagi, avatars embalmed in concrete. His cast metal cards—evoking corrupted Pokémon, burnt-out Tamagotchi shells, or post-internet tarot—nod to collectible culture but with a corrosion that suggests entropy more than value.

Together, the artists share a sensibility of synthetic mythology—what we might call post-consumer animism. This is not merely nostalgia; it’s about the afterlife of images, not their memory. In Bosch’s world, images become gods. In Biscuit’s, they become ghosts.

One particularly poignant moment—if such a word can be salvaged—comes in the strange interplay between Bosch’s massive flat screen displaying Super Metal Mons! in digital mode, and the hand-formed ceramic game boards below. It’s as if the exhibition itself cannot decide what world it belongs to: the frictionless digital arena of endless refresh, or the imperfect physical world where things can chip, fade, and melt.

But perhaps this is the crux of One Of Us Is Real And It's Not You: a shared acknowledgment that we now live in a culture where everything is “play”—even decay, even collapse. And in that play, Bosch and Biscuit find something feral and future-facing.

This is not world-building. It’s world-haunting.