No one ever really leaves the internet; they just change rooms. “Poets, Gamblers, Fools,” Jon Rafman and Parker Ito’s compact collaboration at Lubov, slips through those rooms like a cold draft, reanimating a milieu that refuses to fossilize.

In August 2009, a Google Maps car photographed itself running over a deer—an accidental memento mori that would spark a friendship between two artists destined to shape what we now, reluctantly, call Post-Internet art. When Parker Ito emailed Jon Rafman about this digital roadkill, neither could have predicted they were standing at the threshold of a movement that would redefine contemporary art's relationship with the network age.

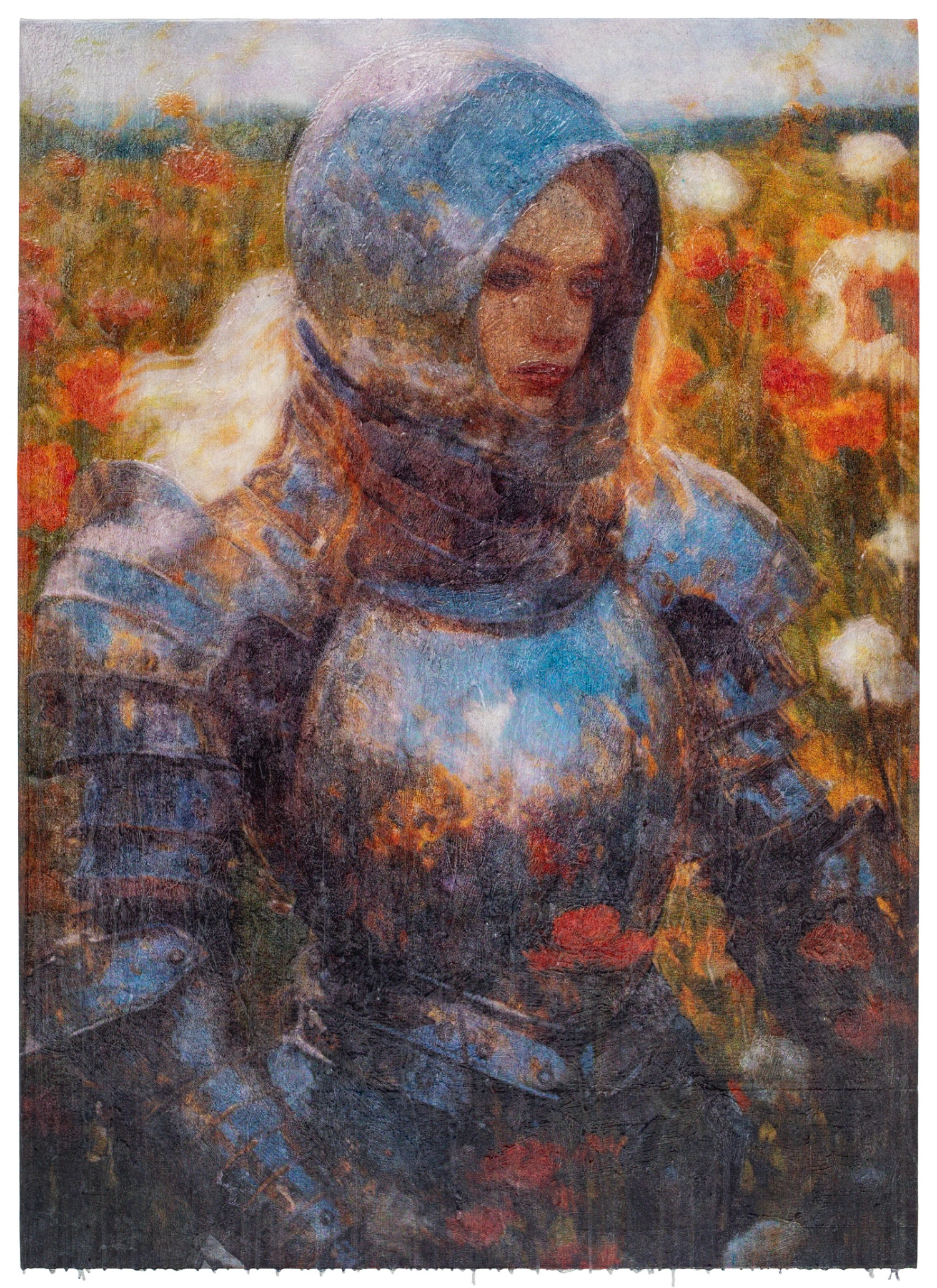

"Poets, Gamblers, Fools" at Lubov resurrects not just the collaboration between Rafman and Ito, but interrogates the corpse of a cultural moment that refuses to stay buried. The exhibition title itself reads like a tarot spread for the artistic condition: the poet seeking beauty, the gambler accepting loss as the price of potential gain, the fool stepping blindly into the unknown. These archetypes map perfectly onto the Post-Internet generation's trajectory—from utopian dreamers to market darlings to historical footnotes, all within a single decade.

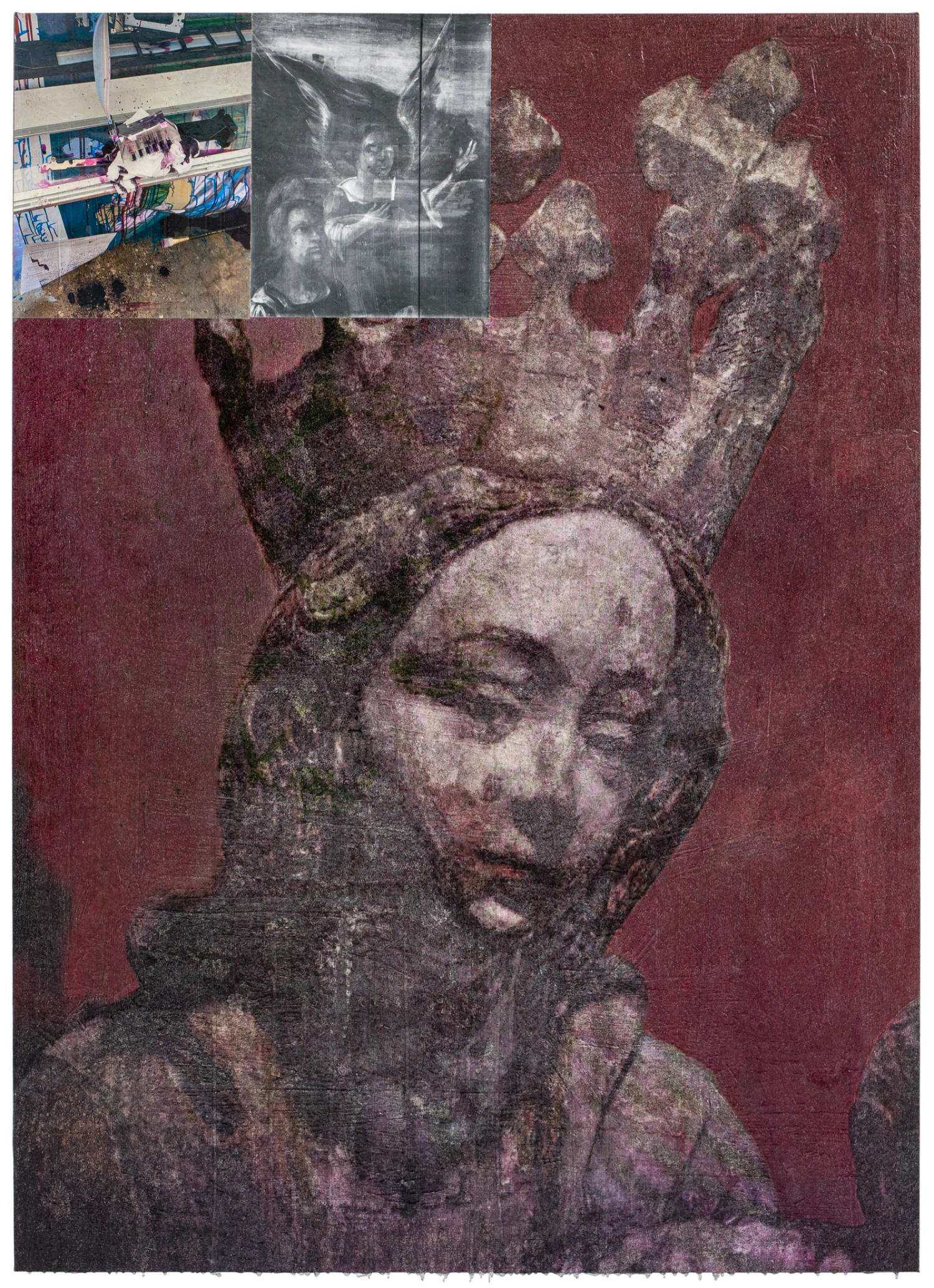

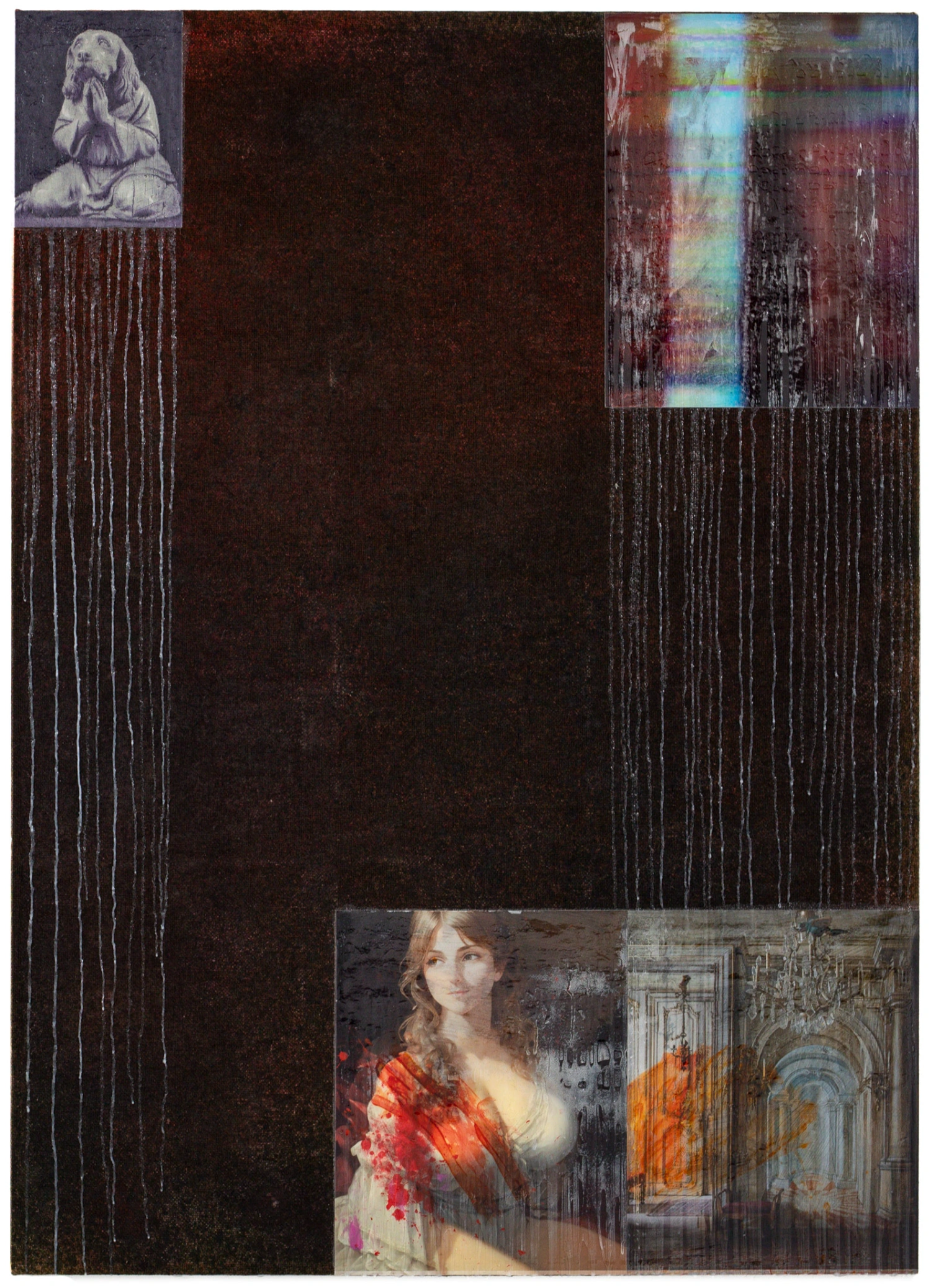

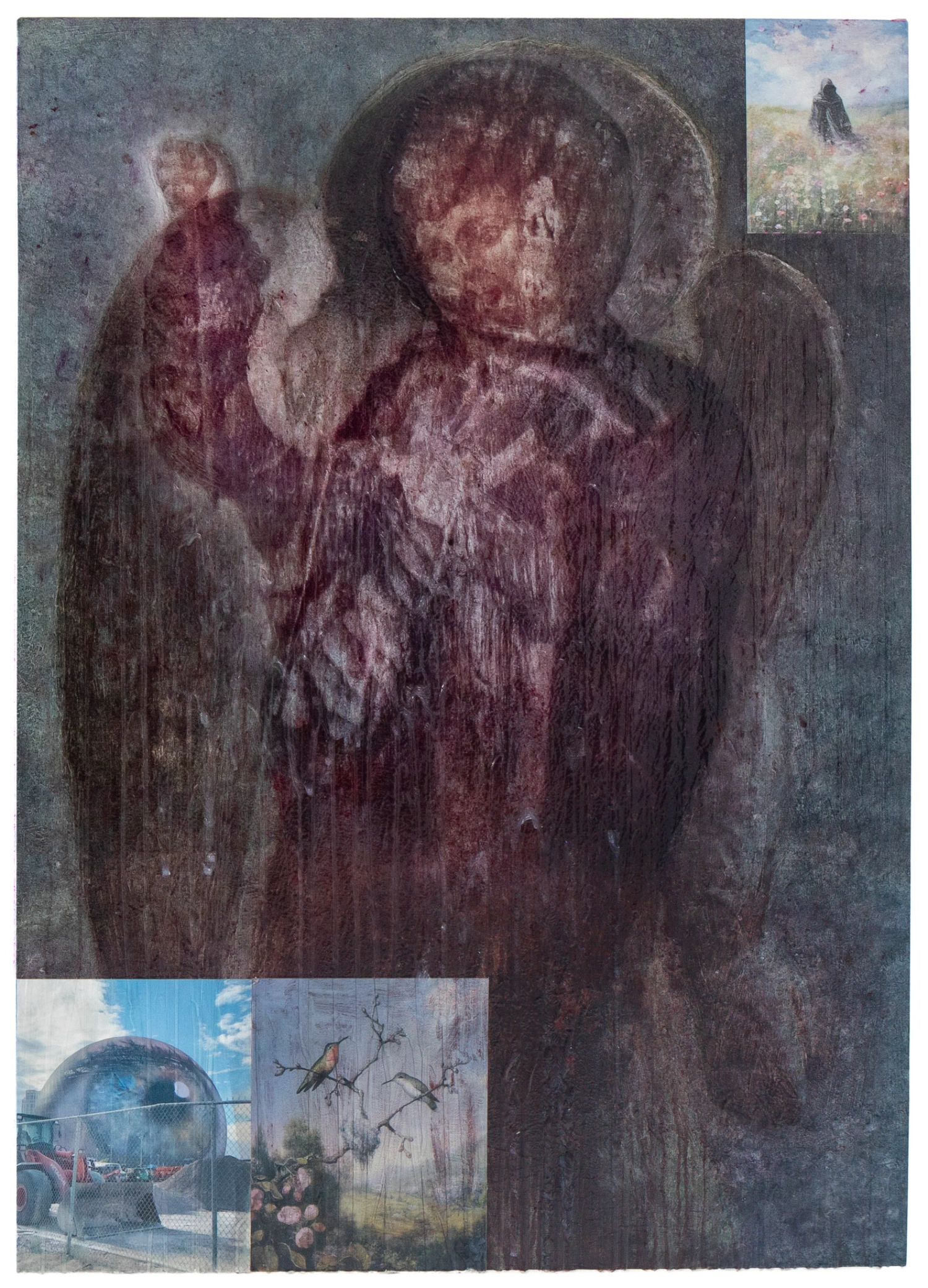

The show's promotional imagery—a skeleton clubbing a painter while the painting survives—distills the exhibition's core paradox. "Death takes the painter but leaves the painting," as the curatorial text notes, invoking the Latin maxim "Ars Longa, Vita Brevis." But what happens when the movement itself dies? Post-Internet, as Ito carefully delineates, exists in three simultaneous states: as universal condition (everything after the internet is post-internet), as market category (the sanitized aesthetic of digital natives in white cube spaces), and as specific historical moment (2006-2013's experimental online communities).

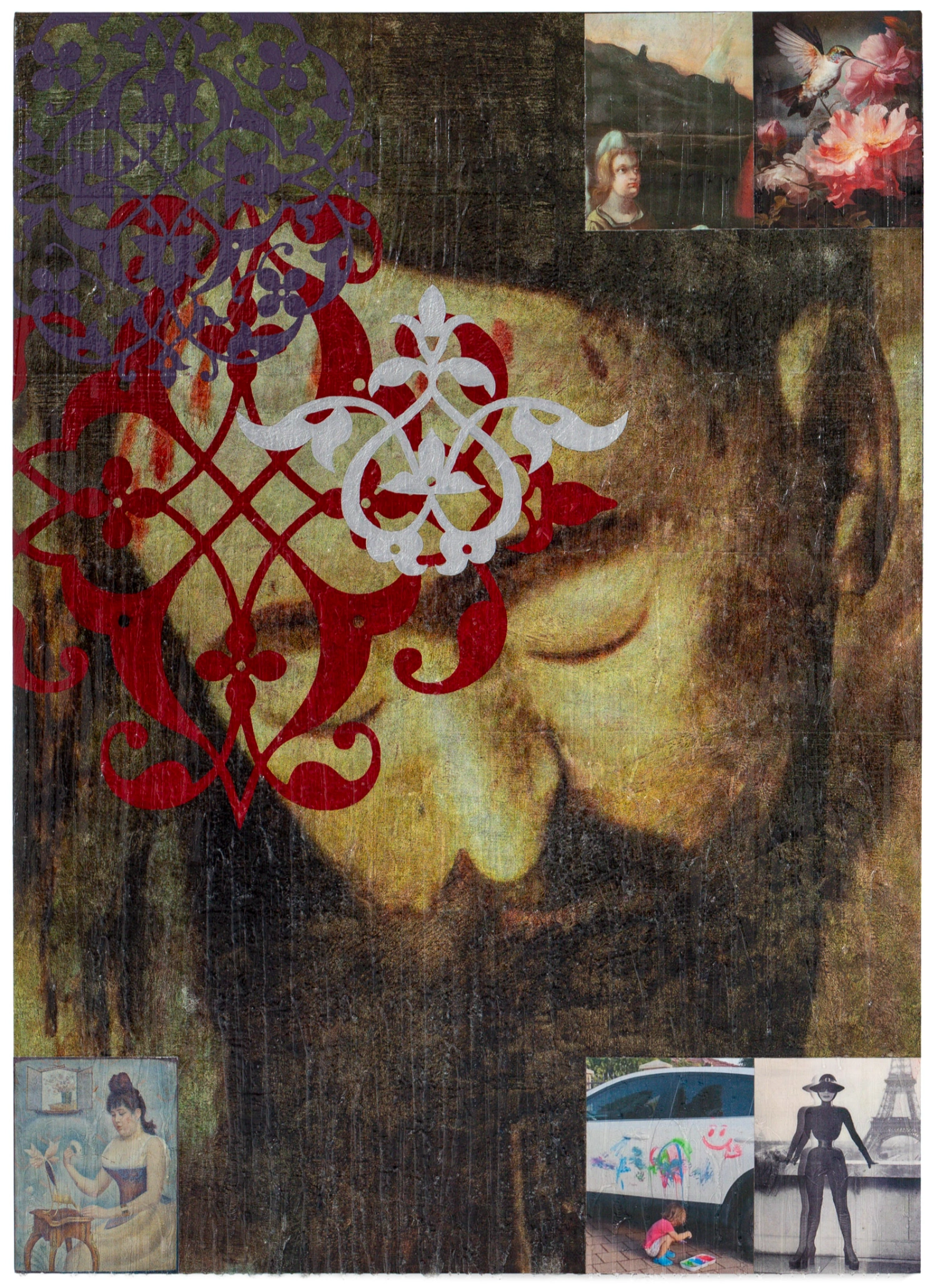

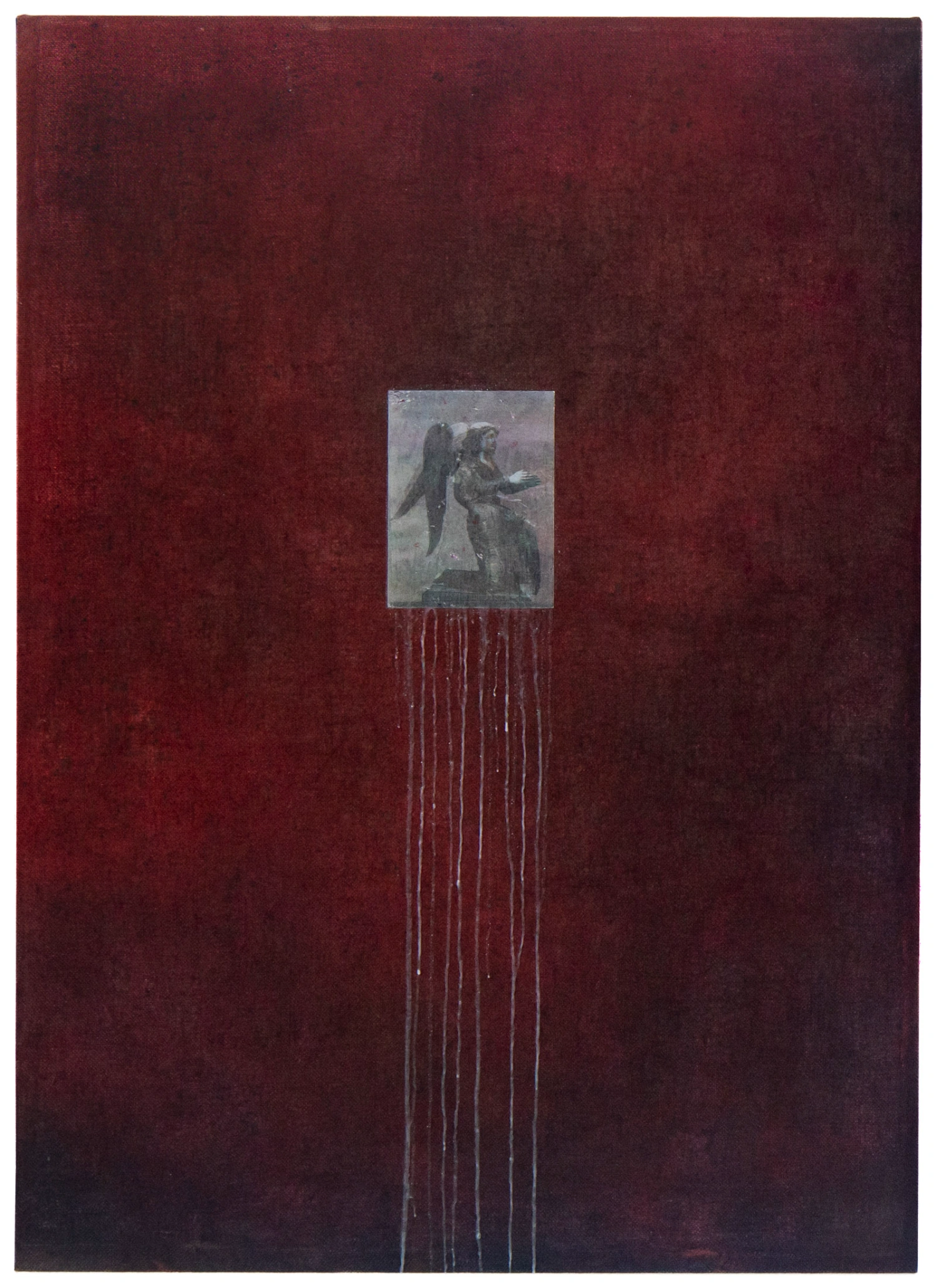

It's this third definition that haunts the gallery. The exhibition becomes a séance for "a high watermark in the 21st century for that desire to change the course of art history." Bold claim? Perhaps. But Rafman and Ito earned their stripes in surfclubs and chat rooms, spaces where the edges of digital culture "had not made themselves completely visible yet, seemingly limitless, raw and unexplored." They weren't making art about the internet; they were making art through it, with it, as it.

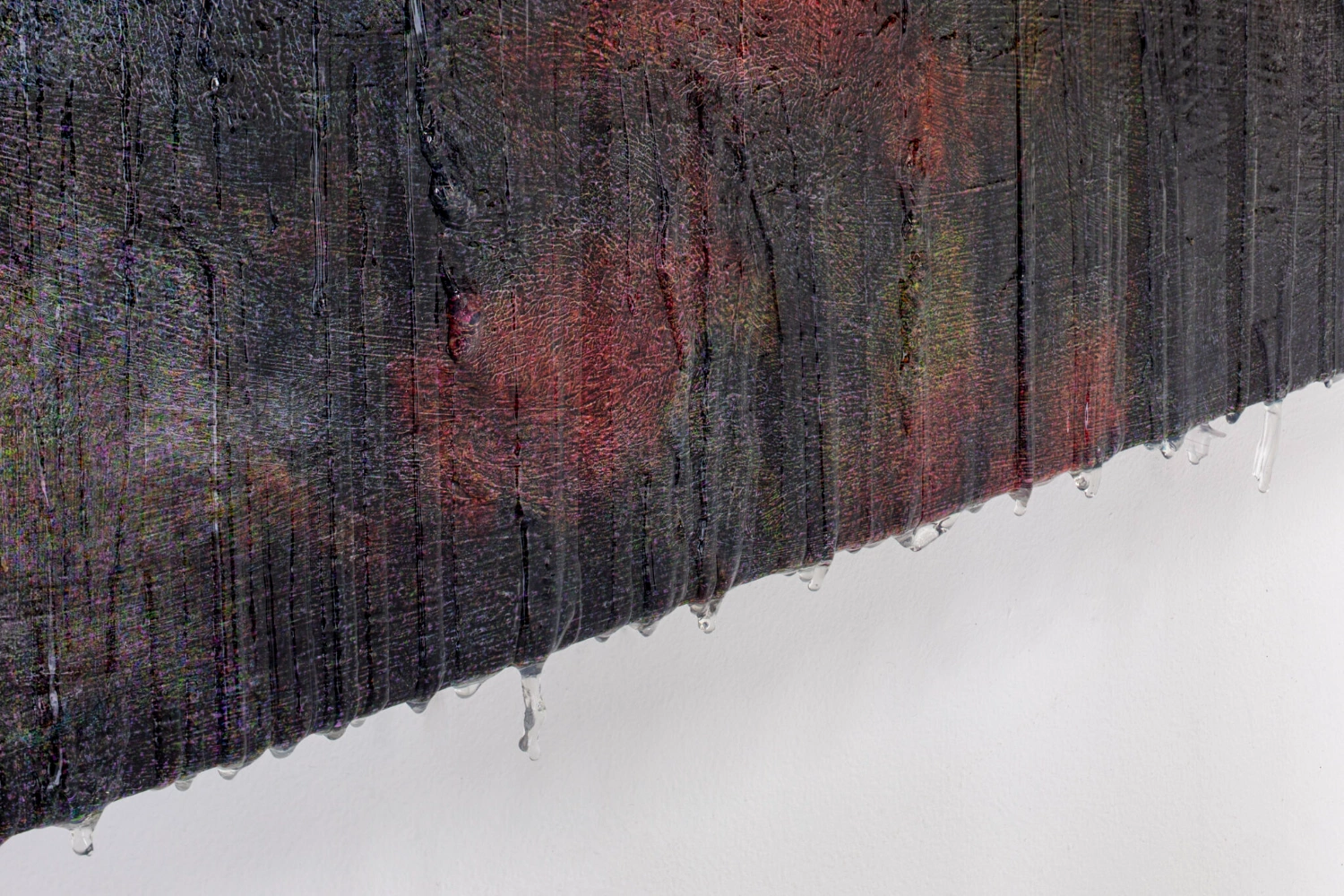

The democracy of Web 2.0—its "culture of defaults and presets"—provided the raw material, but the spirit transcended the technology. As the text insists, one doesn't reduce a painting to "fats, pigments, and threads of linen." Similarly, Post-Internet's legacy isn't in its GIFs and Google Street View captures, but in its embodiment of "the will to participate in the epochal blooming of the art historical process."

What makes this exhibition urgent isn't nostalgia but diagnosis. "Today we are faced with indecision and confusion about what is worth pursuing in art," the curatorial statement observes. Post-Internet persists as a ghost—"not dead, but no longer alive"—demanding we make "a definitive judgment about the past." The deer that Google's camera car killed fifteen years ago continues to generate meaning through its image. Similarly, Post-Internet's afterlife might prove more generative than its original incarnation.

Rafman and Ito understand that movements don't truly die; they transform into hauntings. Their exhibition doesn't attempt resurrection but rather channels the spectral energy of a moment when "anything was possible." In our current artistic malaise, perhaps we need these ghosts—these poets, gamblers, and fools—to remind us that history demands not just documentation but active participation in its unfolding.

The painter falls; the painting continues. The network molts; the will remains. Post-Internet’s ghost doesn’t seek closure. It wants accomplices.